Asthma is a respiratory condition characterised by spasms in the bronchi of the lungs, resulting in breathing difficulties. It’s normally associated with allergic reactions or other forms of hypersensitivity. This blog will take a brief look at some evidence that suggests a central role for plant-based diets in the treatment of asthma and the prevention of asthmatic attacks.

Blog Contents

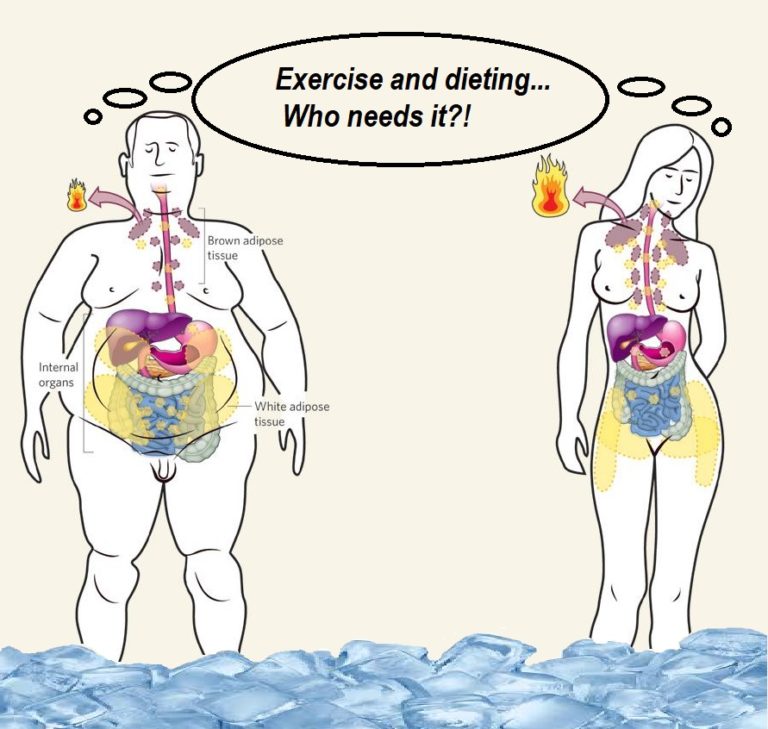

Healthy body weight and asthma

- two 2013 studies on asthma in children found that being overweight increases the risk of developing asthma by 35%, while being obese as a child increases the risk by 50% 1 and losing excess weight in children improves lung function2

- this was further supported by a 2018 study: ““There are few preventable risk factors to reduce the incidence of asthma but our data show that reducing the onset of childhood obesity could significantly lower the public health burden of asthma.” 3

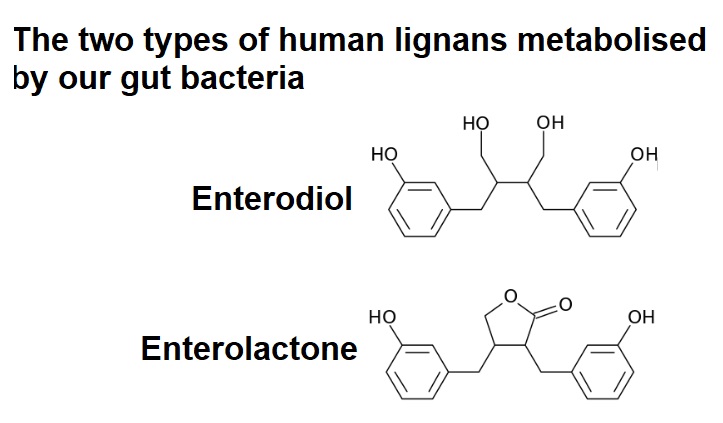

Fatty acid intake and asthma

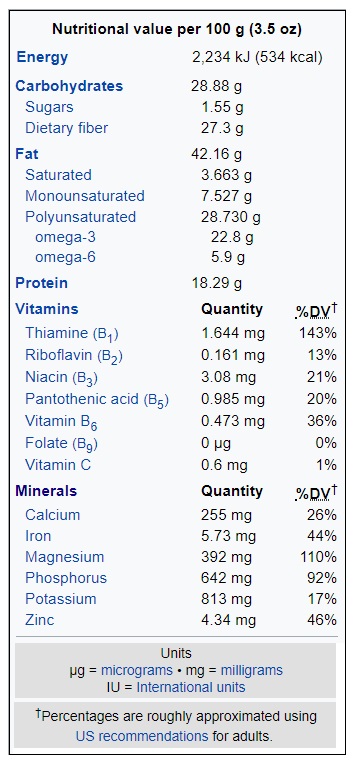

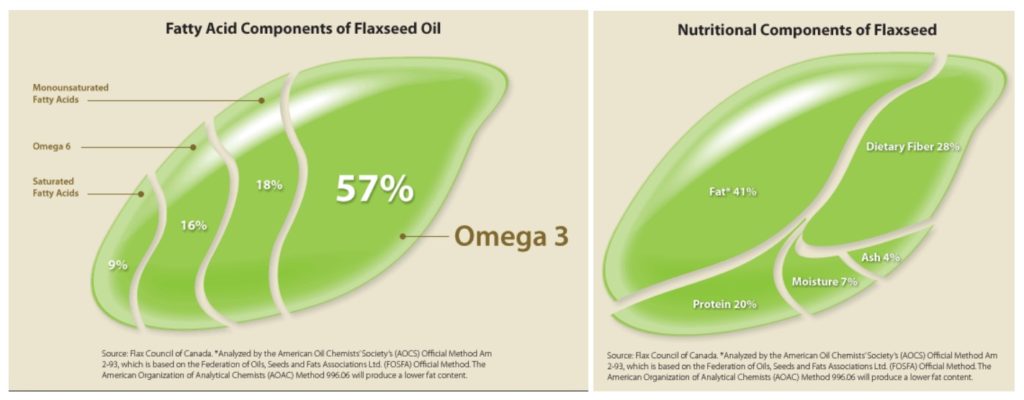

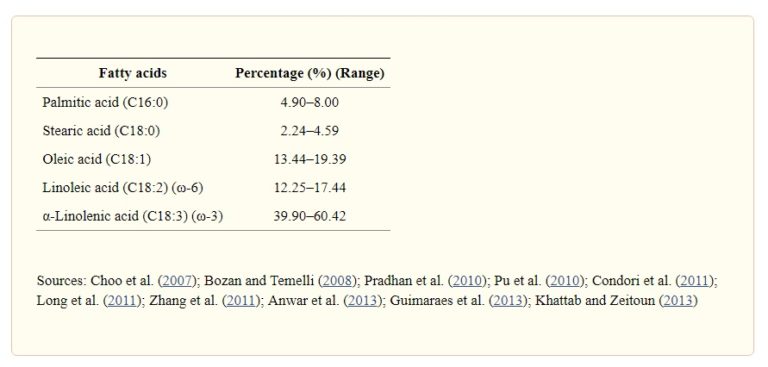

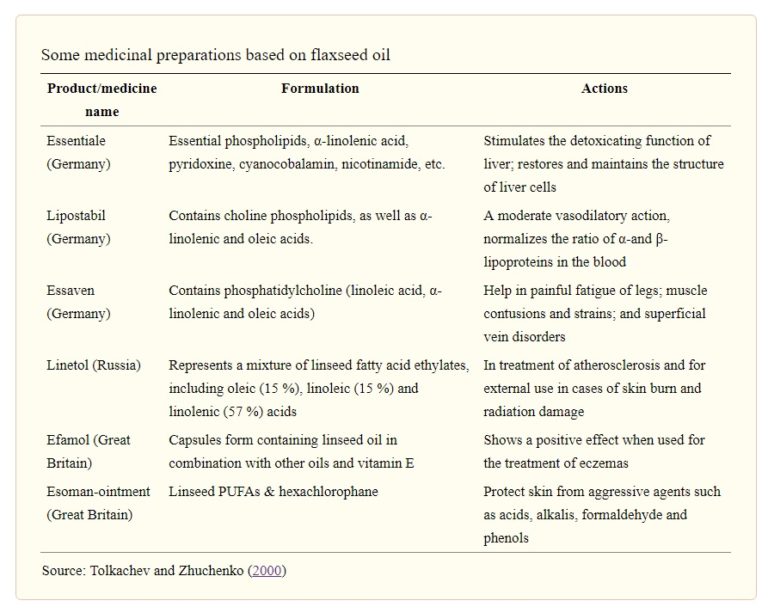

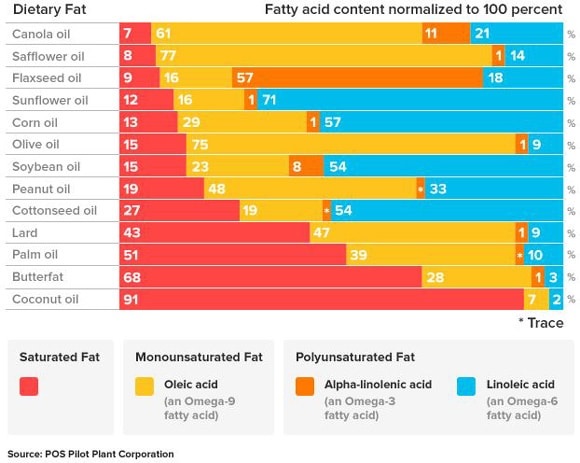

Omega-6 fatty acids are mostly found in animal products. They are also found in margarines and other vegetable oils. The specific amounts of oil-based fats are shown in the chart below 4 . N.B. Consuming any form of oil or fat that’s been separated from its original food source is not to be advised, for reasons covered in previous blogs. 5 6 7 .

- arachidonic acid (a long-chain omega-6 fatty acid) is found mainly in animal foods and has been shown to be a precursor of leukotrienes which have bronchoconstrictive effects 8 . Leukotrienes are a form of pro-inflammatory molecule released by mast cells during asthma attacks 9

- omega-3 fatty acids, on the other hand, have been shown 10 to have anti-inflammatory effects

- a higher ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids in the diets of children has been shown 10 to have a significant association with an increased risk of asthma

- omega-6 fatty acids have been shown 11 to hinder the incorporation of omega-3 fatty acids into tissue lipids and plasma

- while some studies suggest 12 that fish-based omega-3 intake improves asthma symptoms in children, there are other studies 13 which contradict this and also suggest that such benefits in adults have not been proven

- there are persuasive reasons for getting your omega-3 from walnuts, flaxseeds/chia seeds and/or plant-based omega-3 supplements rather than eating fish or using fish oil supplements 14 15

Saturated fat and asthma

- evidence suggests 16 that when asthmatics eat diets containing high levels of total and saturated fat, there is an increase in the expression of those genes involved in airway inflammation

- a 2010 study concluded 17 that high fat diets are able to inhibit the asthmatic’s response to the asthma medication Ventolin (albuterol)

Dairy products and asthma

- a study 18 showed that pregnant women consuming low-fat yogurt once or more a day or low-fat milk 5.5 times or more a week had a 21% and 8% higher risk, respectively, for having a baby which would be diagnosed with asthma, as compared with women consuming no dairy

- a 2015 study 19 found roughly 50% greater asthma prevalence in children who consumed butter 3 or more times a week, compared with those who either never consumed butter or only consumed it occasionally

Fast food and asthma

- a 2013 study 20 found a ~40% increased risk of severe asthma developing in children and adolescents who consumed fast food 3 or more times a week, as compared with those who either never ate fast food or ate it only occasionally

Nuts, seeds and asthma

- although tree nuts and peanuts can be allergenic to some people, a 2012 Danish study 21 found that nut intake during pregnancy was actually inversely related to an asthma diagnosis in their offspring at 18 months of age

- a 2009 French study 22 looked at the risk that French women have of frequent asthma attacks (1 or more per week), and found that the risk was lower in women who consumed the highest amount of nuts and seeds (>5.3 g/day) when compared with those with the lowest consumption (≤ 1.0 g/day)

Salt and asthma

- whilst there is evidence 23 that consuming a low-sodium (salt) diet appears to reduce bronchoconstriction in asthmatics in response to exercise, there is no strong evidence that a low-sodium diet (of itself) reduces the prevalence or severity of asthma 24

- considering that salt is known 25 to be pro-inflammatory, it makes sense that it’s wise to avoid adding salt to your food and, of course, avoiding procesed foods which are known to be high in salt

- a 2014 study concluded: “…our findings suggest that higher sodium consumption is associated with greater adiposity, leptin resistance, and inflammation independent of total energy intake and sugar-sweetened soft drink consumption.” 26

Fruits, vegetables and asthma

- fruits, vegetables and other foods high in antioxidants have been shown 27 to produce ~45% lower risk for asthma in those children and adults who consume the most amount of fruits and vegetables, as compared with those who eat the least amount

- a 2013 study 28 found that individuals who ate the lowest amount of fruit and vegetable (3 servings/day – typical of Western diets) had more than 50% increased risk of asthma exacerbation than those who ate 7 daily servings of fruits and vegetables

- the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) recommended that clinical advice should be to increase the net intake of fruits and vegetables as a way of reducing the risk of asthma, particularly in children 29

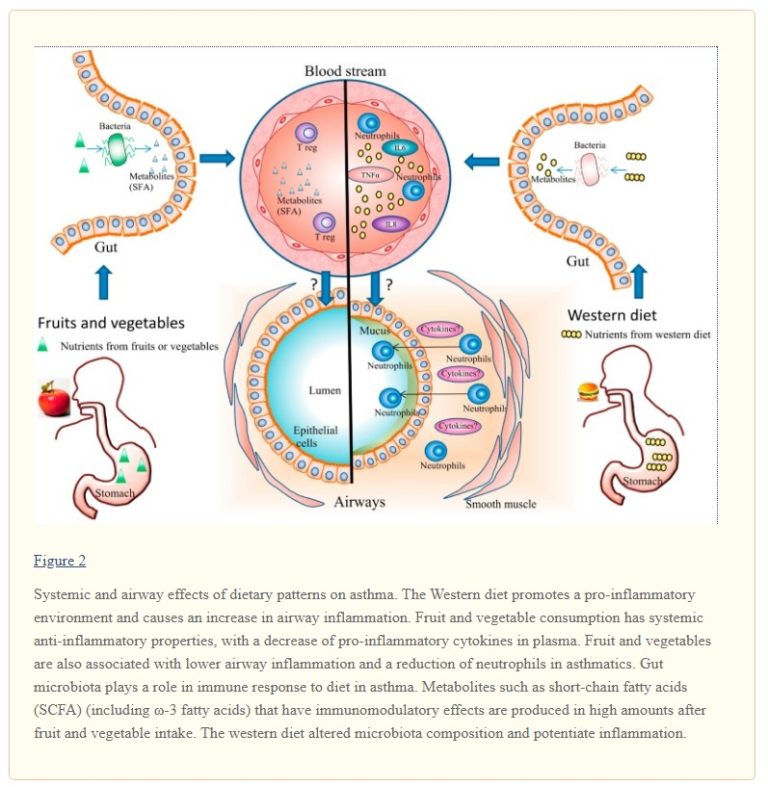

- a 2017 study concluded “higher intakes of fruits and vegetables may have a positive impact on asthma risk and asthma control.” 30 and provided an interesting schematic that compared the airway effects of the Western diet and a diet high in fruit and veg:

Vegetarian, vegan diets and asthma

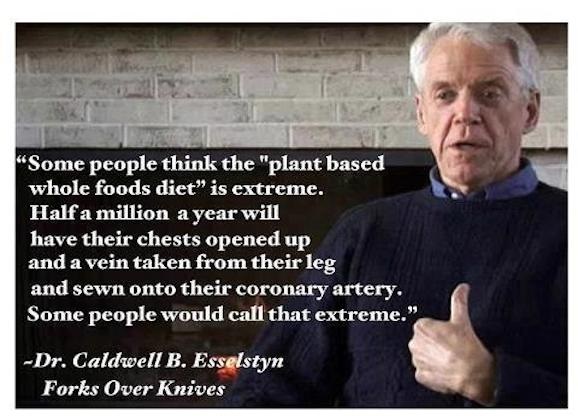

- a 1994 study 31 of almost 28,000 Seventh-day Adventists found that vegetarian women amongst the group reported a lower incidence of asthma, as compared to women who ate omnivore diets. “The theoretical basis for the value of vegan diets is the absence of potential triggers, particularly dairy products and eggs, as well as a relative lack of arachidonic acid.” 32

- although the so-called Mediterranean diet is something of an anathema these days – with the spread of the modern Western diet across the continent – a 2014 review 33 found 7 out of 10 studies noted that there was a protective effect of a Mediterranean diet on the incidence of child asthma

- a 1985 study used a vegan diet for 1 year as an alternative therapy to typical asthma drugs for a group of 35 asthma patients. They found a significant decrease in asthma symptoms as a result of this simple dietary intervention: “…71% reported improvement at 4 months and 92% at 1 yr. There was a significant improvement in a number of clinical variables; for example, vital capacity, forced expiratory volume at one sec and physical working capacity, as well as a significant change in various biochemical indices as haptoglobin, IgM, IgE, cholesterol, and triglycerides in blood. Selected patients, with a fear of side-effects of medication, who are interested in alternative health care, might get well and replace conventional medication with this regimen.” 34

Sugar-sweetened beverages and asthma

- a 2009 US study 35 found an increased risk of developing asthma in those students who drank soda (fizzy drinks): 2 regular sodas a day meant a 28% increased risk, while 3 or more regular sodas a day meant a 64% increased risk. It was also pointed out that previous studies found asthma symptoms were worsened by regular soda consumption

- a follow-up study 36 on non-obese adults found that those who consumed 2 or more sugar-sweetened beverages a day had ~65% increased risk of developing asthma, as compared to those who didn’t consume any such beverages

- and it’s not just sodas that are the problem – a further 2016 US study 37 found that asthma risk in children between 2 and 9 years of age was significantly higher when they consumed apple juice or high fructose corn syrup-sweetened beverages 5 or more times a week, as compared to consuming only 1 or no such beverages per month

Alcohol and asthma

- a 2012 study 38 found a U-shaped association between alcohol consumption and the development of new onset asthma in adults – that is, moderate weekly intake (1-6 units/week) showed a reduced risk, whilst those who never/rarely drank (<1 unit/month) and heavy drinkers (≥4 units/day) showed an increased risk. The risk of new-onset asthma was also shown to be lower for subjects with wine preference when compared with beer preference. However, the study authors admit that their findings were not statistically significant

- contradictory information is provided by other authorities, including Asthma UK 39 , which claims that alcohol does exacerbate asthma symptoms, and a study in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 40 , which states that wines are the greatest triggers for asthma attacks

- whilst there’s obviously disagreement on this subject, and thus further research would be useful, previous blogs 41 42 have explained the reasons why any amount of alcohol intake has been shown to be potentially harmful

Vitamin D status and asthma

- a 2014 meta-analysis 43 found that increased vitamin D deficiency was associated both with an increase in the incidence of asthma in general and with a decrease in lung function in asthmatic children in particular

- whilst there is some disagreement on the benefits of vitamin D supplementation as a means of treating/preventing asthma in children 44 , an additional study 45 reported that those children who took vitamin D supplements reduced their risk of asthma by ~25%, as compared with children without supplemental vitamin D

Breastfeeding and asthma

- a 2004 study 46 on the therapeutic measures for preventing the development of both allergic rhinitis and asthma, made the following suggestions for decreasing the the risk for developing asthma in babies during breastfeeding:

- ensure that babies are breastfed for the first 4-6 months of life

- avoid dairy products until at least 1 year old

- avoid eggs until at least 2 years old

- avoid nuts and fish until at least 3 years old

Inhalers and asthma

An interesting article appeared in The Telegraph today 47 entitled “Asthma inhalers as bad for the environment as 180-mile car journey, health chiefs say.” It points out the dangers to the environment of the hydrofluorocarbons (a powerful greenhouse gas) contained in the majority of the asthma inhalers (known as metered dose inhalers of MDI’s) used in the UK.

- Nice (The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) was reported to have calculated that “…five doses from an MDI have the same carbon emissions as a nine-mile trip in a typical car. The devices usually contain 100 doses. By contrast, dry powder inhalers are only around one fifth as bad for the environment.”

- more than 5.4 million people in the UK receive treatment for asthma, including 1.1 million children

- Britain has some of the highest rates in Europe, with around three people a day dying as a result of the condition

Whilst inhalers do, of course, save lives and users should only consider making changes in consultation with their doctor, they are known 48 to have side effects. Making dietary changes that help to prevent and treat asthma does seem to be a much better alternative, especially since the only side effects appear to be positive ones.

Final thoughts

The foregoing appears to suggest that there is, indeed, an important role for plant-based diets in the prevention and treatment of asthma. Such diets (so long as they are based on wholefood plants and avoid processed plant foods) are excellent for the maintenance of healthy weight and can provide the ideal fatty acid profile.

It’s clear that some particular foods are best avoided completely, including dairy products, fast food, sugar-sweetened beverages and, arguably, excessive amounts of salt – especially when contained in processed foods.

If you suffer from asthma, perhaps a useful way to check whether this dietary approach will alleviate your asthma is to stick with your current diet for a specific time, but keep a detailed daily record of asthma symptoms. After this, change to a non-SOS WFPB (no added sugar, salt or oil wholefood plant-based diet) for a similar specific period of time and maintain the daily diary. You would then be able to compare the frequency and intensity of symptoms between the two periods.

Should you decide to do this, and would like to share the results, please feel free to write to me with your findings and I will aim to publish them in a subsequent blog.

References & Notes

- Egan KB, Ettinger AS, Bracken MB: Childhood body mass index and subsequent physician-diagnosed asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Pediatr 13:, 2013 [↩]

- Moreira A et al: Weight loss interventions in asthma: EAACI evidence-based clinical practice guideline (part I). Allergy 68:425, 2013 [↩]

- Obesity is linked to increased asthma risk in children, finds study BMJ 2018; 363 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k5001. 26 November 2018. [↩]

- Comparison of Dietary Fats Chart [↩]

- Surely Coconut Oil’s better than Butter?! [↩]

- Olive Oil Injures Endothelial Cells [↩]

- Coconut Oil is ‘Pure Poison’ says Harvard Professor [↩]

- Pharmacotherapy. 1997 Jan-Feb;17(1 Pt 2):3S-12S. Arachidonic acid metabolites: mediators of inflammation in asthma. Wenzel SE [↩]

- What are leukotrienes and how do they work in asthma? BMJ 1999; 319 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7202.90 BMJ 1999;319:90 [↩]

- Wendell SG, Baffi C, Holguin F: Fatty acids, inflammation, and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 133:1255, 2014 [↩] [↩]

- Dias CB, Wood LG, Garg ML: Effects of dietary saturated and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids on the incorporation of long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids into blood lipids. Eur J Clin Nutr 70:812, 2016 [↩]

- Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018 Jun;294:350-360. doi: 10.1111/pai.12889. The role of fish intake on asthma in children: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Papamichael MM, Shrestha SK, Itsiopoulos C, Erbas B. [↩]

- Brannan JD et al: The effect of omega-3 fatty acids on bronchial hyperresponsiveness, sputum eosinophilia, and mast cell mediators in asthma. Chest 147:397, 2015 [↩]

- Omega 3 Supplements = Snake Oil [↩]

- Nutritionfacts: Omega-3 Fatty Acids [↩]

- Li Q et al: Changes in Expression of Genes Regulating Airway Inflammation Following a High-Fat Mixed Meal in Asthmatics. Nutrients 8:, 2016 [↩]

- American Thoracic Society. “High-fat meals a no-no for asthma patients, researchers find.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 17 May 2010. [↩]

- Maslova E et al: Low-fat yoghurt intake in pregnancy associated with increased child asthma and allergic rhinitis risk: a prospective cohort study. J Nutr Sci Jul 06 [↩]

- Saadeh D et al: Prevalence and association of asthma and allergic sensitization with dietary factors in schoolchildren: data from the french six cities study. BMC Public Health 15:, 2015 [↩]

- Ellwood P et al: Do fast foods cause asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema? Global findings from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) phase three. Thorax 68:351, 2013 [↩]

- Maslova E et al: Peanut and tree nut consumption during pregnancy and allergic disease in children-should mothers decrease their intake? Longitudinal evidence from the Danish National Birth Cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol 130:724, 2012 [↩]

- Varraso R et al: Dietary patterns and asthma in the E3N study. Eur Respir J 33:33, 2009 [↩]

- Mickleborough TD: Salt intake, asthma, and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction: a review. Phys Sportsmed 38:118, 2010 [↩]

- Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000436. Dietary salt reduction or exclusion for allergic asthma. Ardern KD. [↩]

- Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012 Nov;66(11):1214-8. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.110. Epub 2012 Aug 22. Dietary salt intake is related to inflammation and albuminuria in primary hypertensive patients. Yilmaz R, Akoglu H, Altun B, Yildirim T, Arici M, Erdem Y. [↩]

- Pediatrics. 2014 Mar; 133(3): e635–e642. Dietary Sodium, Adiposity, and Inflammation in Healthy Adolescents. Haidong Zhu et al. [↩]

- Seyedrezazadeh E et al: Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of wheezing and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 72:411, 2014 [↩]

- Grieger JA, Wood LG, Clifton VL: Improving asthma during pregnancy with dietary antioxidants: the current evidence. Nutrients 5:3212, 2013. [↩]

- Asthma and dietary intake: an overview of systematic reviews. Garcia-Larsen V, Del Giacco SR, Moreira A, Bonini M, Charles D, Reeves T, Carlsen KH, Haahtela T, Bonini S, Fonseca J, Agache I, Papadopoulos NG, Delgado L. Allergy. 2016 Apr; 71(4):433-42. [↩]

- Nutrients. 2017 Nov; 9(11): 1227. Published online 2017 Nov 8. doi: 10.3390/nu9111227. Diet and Asthma: Is It Time to Adapt Our Message? Laurent Guilleminault et al. [↩]

- Knutsen SF: Lifestyle and the use of health services. Am J Clin Nutr 59:1171S, 1994. [↩]

- PCRM: Nutrition Guide for Clinicians: Asthma. [↩]

- Lv N, Xiao L, Ma J: Dietary pattern and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Asthma Allergy 7:105, 2014 [↩]

- J Asthma. 1985;22(1):45-55. Vegan regimen with reduced medication in the treatment of bronchial asthma. Lindahl O, Lindwall L, Spångberg A, Stenram A, Ockerman PA. [↩]

- Park S et al: Regular-soda intake independent of weight status is associated with asthma among US high school students. J Acad Nutr Diet 113:106, 2013 [↩]

- Park S et al: Association of sugar-sweetened beverage intake frequency and asthma among U.S. adults, 2013. Prev Med 91:58, 2016. [↩]

- DeChristopher LR, Uribarri J, Tucker KL: Intakes of apple juice, fruit drinks and soda are associated with prevalent asthma in US children aged 2-9 years. Public Health Nutr 19:123, 2016 [↩]

- Lieberoth S et al: Intake of alcohol and risk of adult-onset asthma. Respir Med 106:184, 2012 [↩]

- Asthma UK: Asthma and alcohol [↩]

- JACI: Alcoholic drinks: Important triggers for asthma. Hassan Vally, BSc (Hons), Nicholas de Klerk, PhD, Philip J. Thompson, FRACP [↩]

- No Amount of Alcohol Consumption is Safe [↩]

- Alcohol – Bad News for Good Bacteria [↩]

- Zhang LL, Gong J, Liu CT: Vitamin D with asthma and COPD: not a false hope? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Genet Mol Res 13:7607, 2014 [↩]

- Fares MM et al: Vitamin D supplementation in children with asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes 8:, 2015 [↩]

- Xiao L et al: Vitamin D supplementation for the prevention of childhood acute respiratory infections: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr 114:1026, 2015 [↩]

- Stanaland BE: Therapeutic measures for prevention of allergic rhinitis/asthma development. Allergy Asthma Proc 25:11, 2004 Jan-Feb [↩]

- The Telegraph: Asthma inhalers as bad for the environment as 180-mile car journey, health chiefs say. [↩]

- Medicinenet.com: What Are the Side Effects of Asthma Inhalers? Medical Editor: William C. Shiel Jr., MD, FACP, FACR [↩]

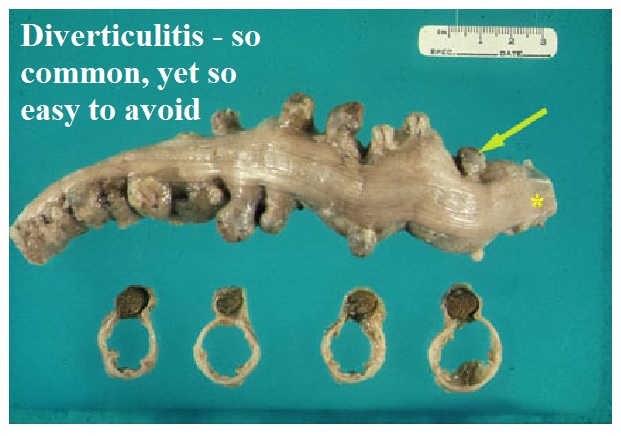

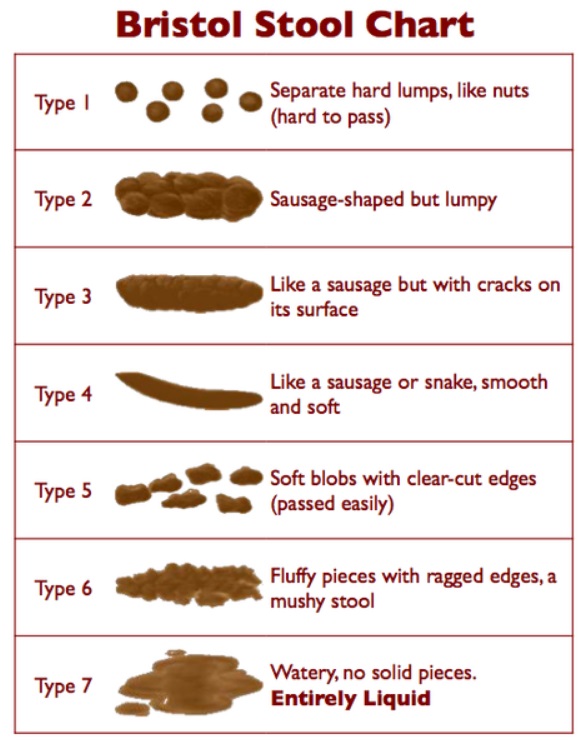

Just as in the previous blog on constipation

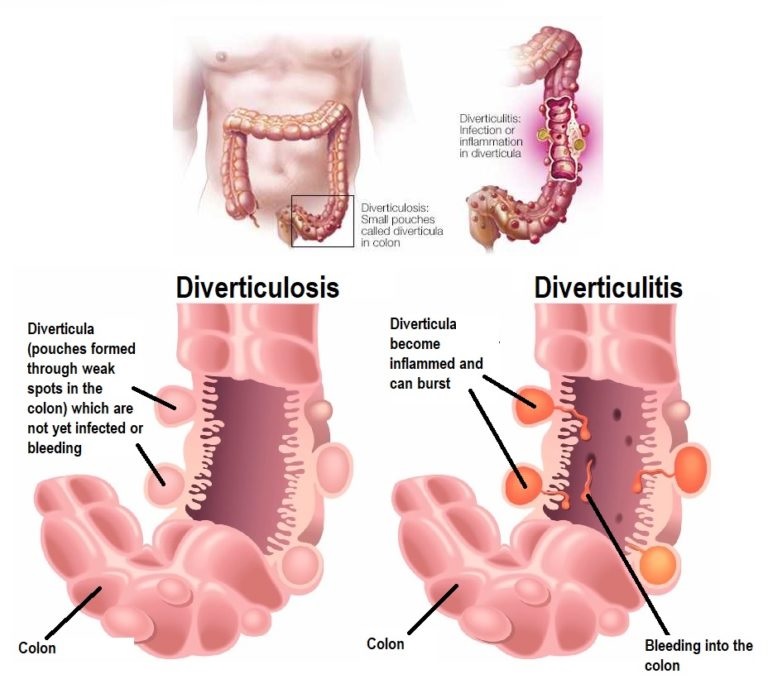

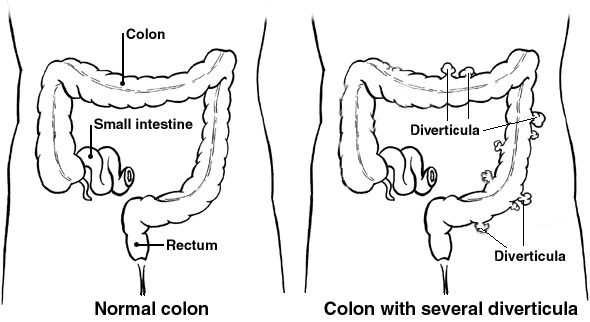

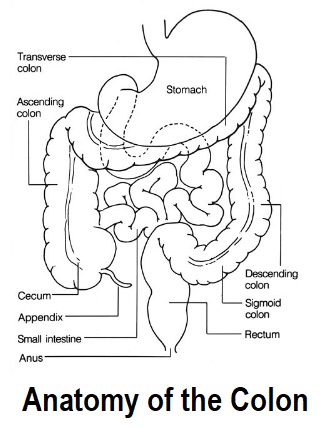

Just as in the previous blog on constipation  Medical advice should always be sought if you have any symptoms of diverticulitis. Most diagnoses are during an acute attack of abdominal pain.

Medical advice should always be sought if you have any symptoms of diverticulitis. Most diagnoses are during an acute attack of abdominal pain.

How much water and fibre is enough? This is a well-debated topic, and was covered in the previous blog

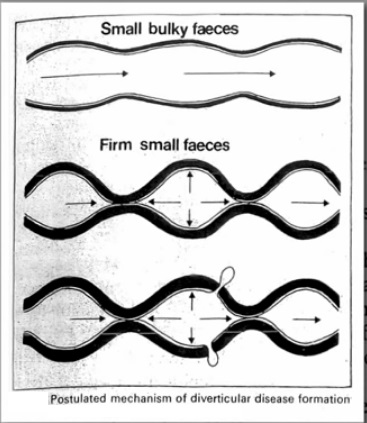

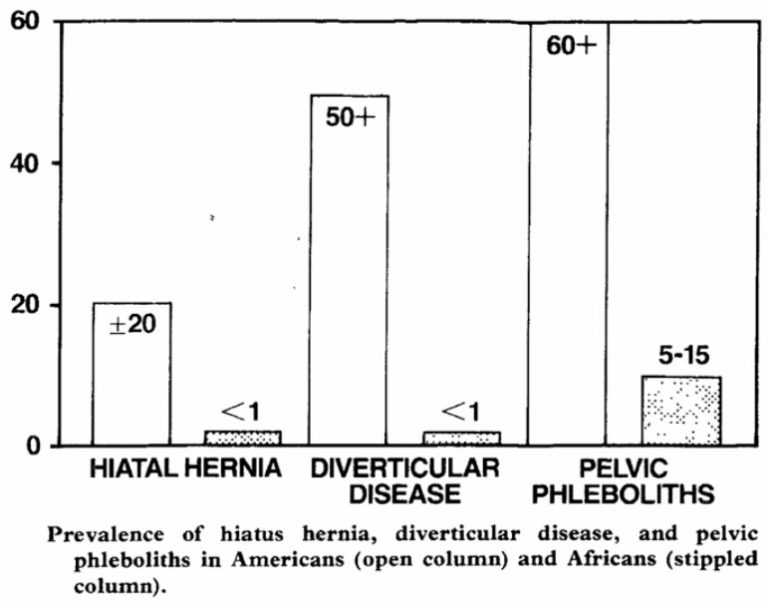

How much water and fibre is enough? This is a well-debated topic, and was covered in the previous blog  But in a 1971 study, by the WFPB pioneer Denis Burkitt and his team

But in a 1971 study, by the WFPB pioneer Denis Burkitt and his team

To clarify just what this flaw of the study was, Dr Greger

To clarify just what this flaw of the study was, Dr Greger

In children, studies show

In children, studies show

Many children with chronic constipation are found

Many children with chronic constipation are found  Cutting out cow’s milk totally, in the diets of those children with cow’s milk sensitivity and constipation, has been shown

Cutting out cow’s milk totally, in the diets of those children with cow’s milk sensitivity and constipation, has been shown

Between around 6 and 12 months of age, the infant will be introduced to “solid” food. It’s during this stage that major mistakes can be made, and bad eating habits (food high in calories and low in nutrients) can be set in motion.

Between around 6 and 12 months of age, the infant will be introduced to “solid” food. It’s during this stage that major mistakes can be made, and bad eating habits (food high in calories and low in nutrients) can be set in motion. One recent story I heard was of a nutritionist who was asked to intervene in a family where the young child refused to eat anything that even appeared to be a vegetable or a fruit, preferring instead to eat a diet existing more or less solely of sweets, crisps and cakes. The nutritionist advised that containers of bite-sized carrots and celery be left around the kitchen for the child to be attracted to eat. The nutritionist then walked past the veg and said something along the lines of “Oh look! How lovely! Carrots. I love them” and then tucked into them with glee. When the father was asked to do the same, as a means of giving positive feedback to the child, he picked up a carrot, bit into it and pulled a face that would have been better suited to a person who had just swallowed a bumble bee. Naturally, the child saw his father’s reaction and the nutritionist could immediately identify the major reason that the child had developed such unhealthy habits.

One recent story I heard was of a nutritionist who was asked to intervene in a family where the young child refused to eat anything that even appeared to be a vegetable or a fruit, preferring instead to eat a diet existing more or less solely of sweets, crisps and cakes. The nutritionist advised that containers of bite-sized carrots and celery be left around the kitchen for the child to be attracted to eat. The nutritionist then walked past the veg and said something along the lines of “Oh look! How lovely! Carrots. I love them” and then tucked into them with glee. When the father was asked to do the same, as a means of giving positive feedback to the child, he picked up a carrot, bit into it and pulled a face that would have been better suited to a person who had just swallowed a bumble bee. Naturally, the child saw his father’s reaction and the nutritionist could immediately identify the major reason that the child had developed such unhealthy habits. Even from the youngest age, infants will be influenced by the sorts of foods they encounter. This isn’t just a matter of flavours, but also of smell, texture, colour, and general variety – the colours of the rainbow.

Even from the youngest age, infants will be influenced by the sorts of foods they encounter. This isn’t just a matter of flavours, but also of smell, texture, colour, and general variety – the colours of the rainbow. I remember that when I was young I asked my mother what tongue was – you know, those greyish-red slices of meat that bear no resemblance to that huge, dripping muscular organ lolling out of the mouths of cows. I’d been eating it for years and it hadn’t dawned on me that what we called slices of tongue was actually part of a dead animal. I mean, they called candyfloss candyfloss, but you don’t floss candy with it! Anyway, once I discovered what it was, I never touched it again. Had I been responsible for cutting it out of the mouth of the dead cow and then slicing and boiling it, perhaps I would have developed an aversion to it at an even earlier age. Who knows?

I remember that when I was young I asked my mother what tongue was – you know, those greyish-red slices of meat that bear no resemblance to that huge, dripping muscular organ lolling out of the mouths of cows. I’d been eating it for years and it hadn’t dawned on me that what we called slices of tongue was actually part of a dead animal. I mean, they called candyfloss candyfloss, but you don’t floss candy with it! Anyway, once I discovered what it was, I never touched it again. Had I been responsible for cutting it out of the mouth of the dead cow and then slicing and boiling it, perhaps I would have developed an aversion to it at an even earlier age. Who knows? Thus, it’s useful for toddlers to grow up learning that they eat when they are hungry – not when they are forced to do so or because they are bored or depressed.

Thus, it’s useful for toddlers to grow up learning that they eat when they are hungry – not when they are forced to do so or because they are bored or depressed. Learning ‘satisfaction-delay’ is a really good skill for children to learn young. If a toddler gets what he or she wants immediately upon request, they don’t learn how to delay pleasurable experiences, and learning how to live with the delayed pleasure of eating is a useful skill that spills over into most aspects of child and adult life.

Learning ‘satisfaction-delay’ is a really good skill for children to learn young. If a toddler gets what he or she wants immediately upon request, they don’t learn how to delay pleasurable experiences, and learning how to live with the delayed pleasure of eating is a useful skill that spills over into most aspects of child and adult life.

In terms of drinks, toddlers should not get used to filling up on sugary drinks. It should go without saying that infants receive their best source of liquids from their mother’s breast milk. Providing drinking fluids during weening is, of course, a natural and essential route, so long as the liquid provided is plain water.

In terms of drinks, toddlers should not get used to filling up on sugary drinks. It should go without saying that infants receive their best source of liquids from their mother’s breast milk. Providing drinking fluids during weening is, of course, a natural and essential route, so long as the liquid provided is plain water.

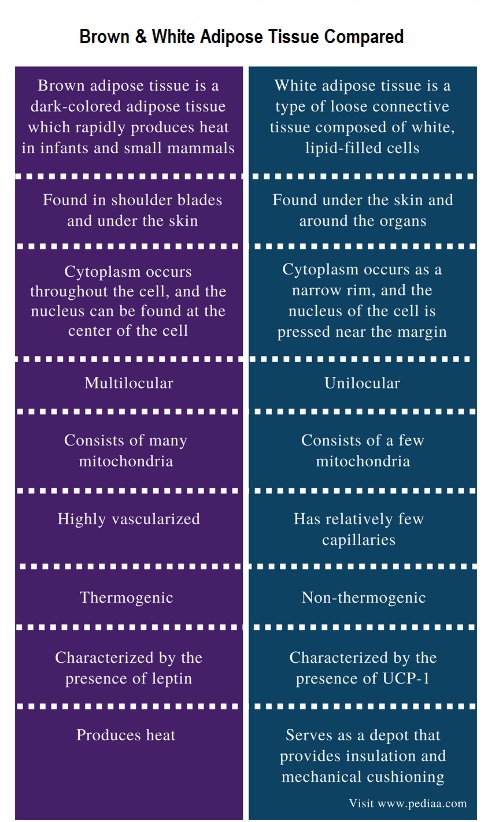

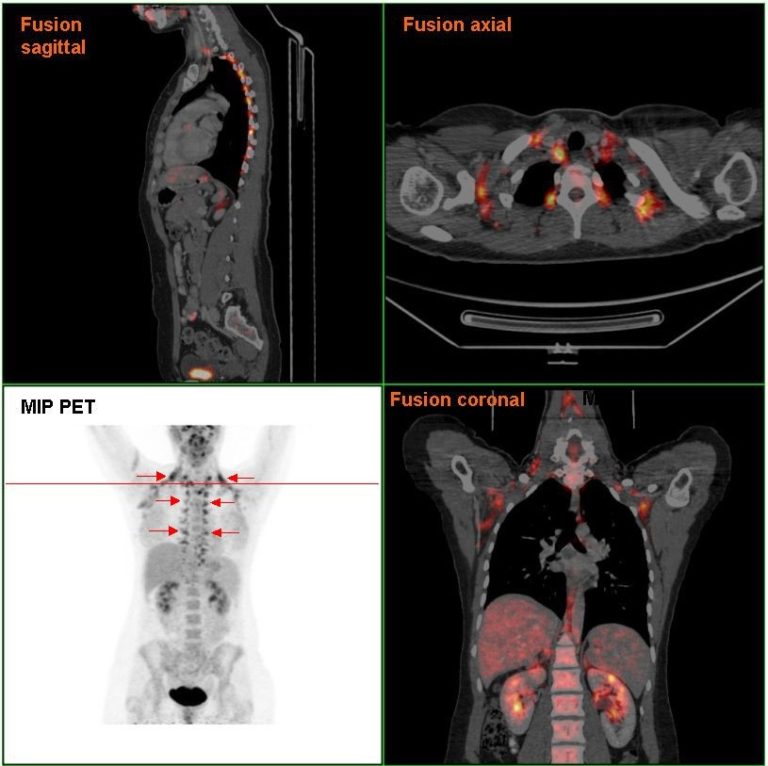

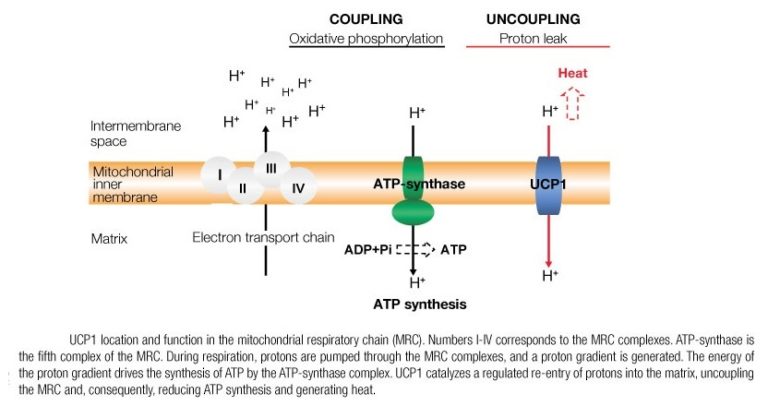

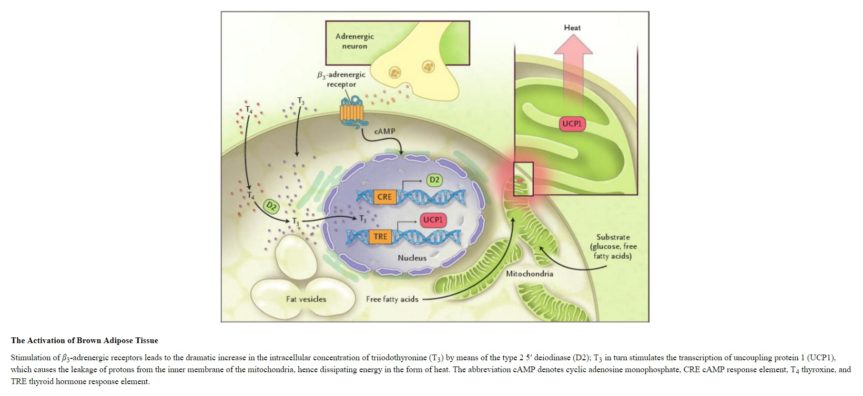

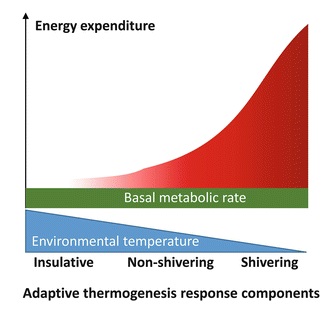

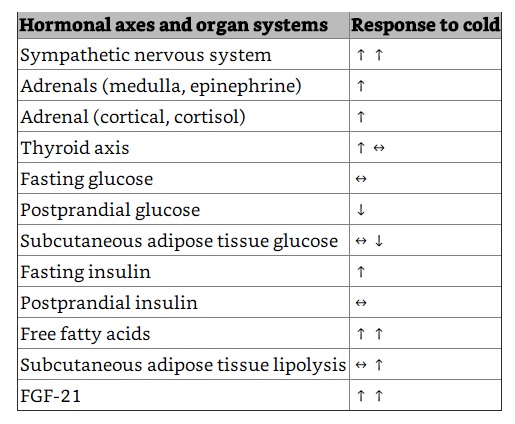

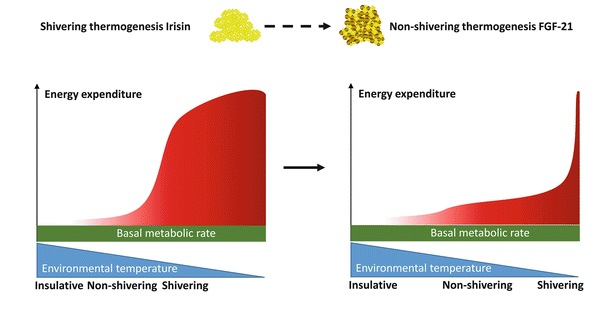

However, the unique ability of BAT to convert energy stores (brown fat) into heat (without needing to use energy-sapping shivering) is achieved through a process within BAT mitochondria (the energy-producing cellular power plants). Instead of the usual process, where ATP (the energy molecule) is produced during oxidative phosphorylation, a protein called thermogenin or UCP1 (Uncoupling Protein 1) promotes a proton leak in the inner membrane of the mitochondria, dissociating the oxidative phosphorylation of substrate from the generation of ATP. In essence, this results in an increase in non-shivering thermogenesis, where the metabolic rate increases, and chemical energy is shunted into heat energy that can then spread around the body via the bloodstream.

However, the unique ability of BAT to convert energy stores (brown fat) into heat (without needing to use energy-sapping shivering) is achieved through a process within BAT mitochondria (the energy-producing cellular power plants). Instead of the usual process, where ATP (the energy molecule) is produced during oxidative phosphorylation, a protein called thermogenin or UCP1 (Uncoupling Protein 1) promotes a proton leak in the inner membrane of the mitochondria, dissociating the oxidative phosphorylation of substrate from the generation of ATP. In essence, this results in an increase in non-shivering thermogenesis, where the metabolic rate increases, and chemical energy is shunted into heat energy that can then spread around the body via the bloodstream.

The leading chef, Richard Corrigan

The leading chef, Richard Corrigan

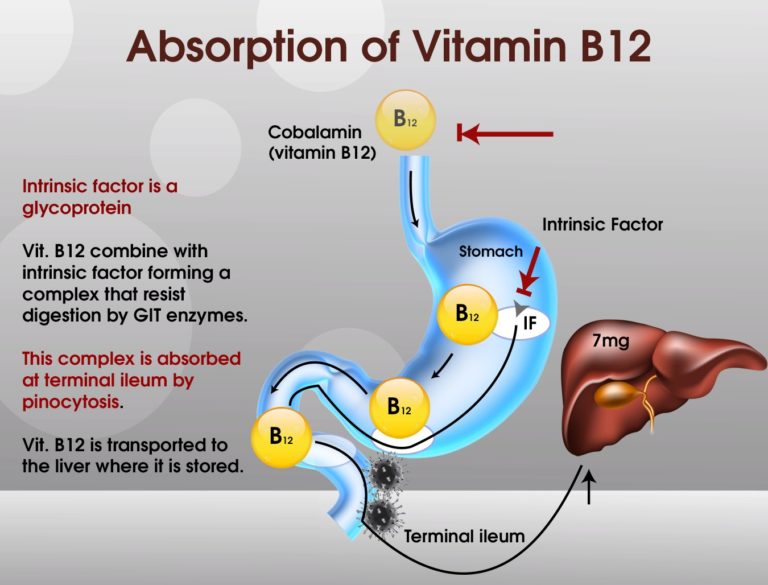

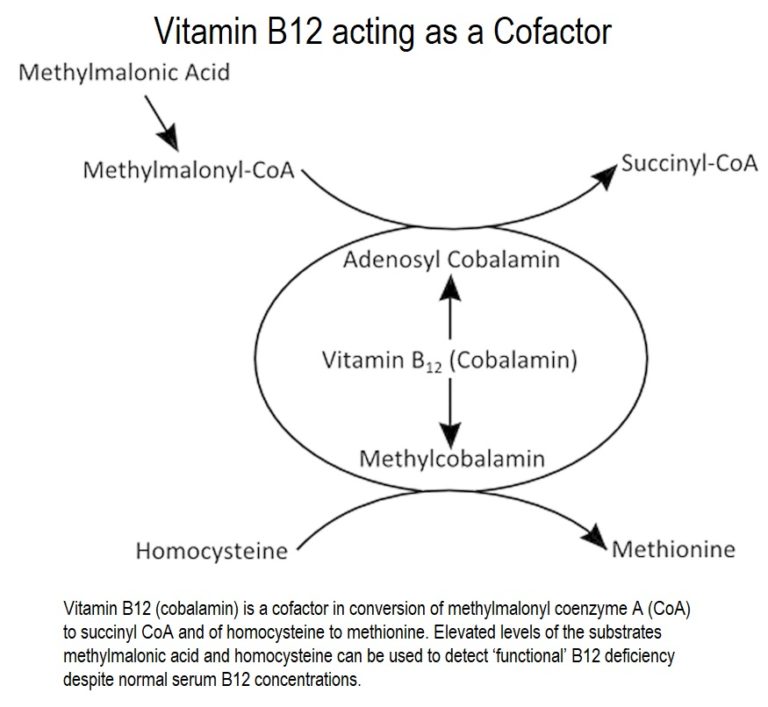

Vitamin B12 acts as a

Vitamin B12 acts as a