“How do you plant-eaters get enough protein?”

You might think that this is a question only asked by people who don’t know much about nutrition; but it is surprising just how many nutritionists, GP’s and writers of nutrition courses ask the same question. In this article, I would like to look at two aspects of protein: firstly, a comparison of protein content in animal and plant foods and, secondly, a look at the dangers of too much (animal) protein in the diet. But first, a quick definition of what protein actually is.

What is protein?

Protein is a nitrogen-containing chemical used to create body tissue as well as other chemicals (for instance, enzymes and hormones) that are very important in terms of participating in metabolism and maintaining the body in working order. Protein molecules are large and composed of long chains (polymers) of carefully sequenced amino acids. There are a huge number of different kinds of proteins, all of which are distinguished by the order that exists for the amino acids in that chain or polymer. The primary function of protein is as the basis for the almost unlimited number of enzymes, and enzymes are the molecules within the body that control metabolism. It is one of the three so-called macronutrients, the other two being fats (lipids) and carbohydrates which are composed of hydrogen and carbon.

It’s useful to understand that these macronutrients – and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), for that matter – do not exist or function in isolation within the body. They work together as combinations, not as distinctly different entities, also working together within individual molecules. For example, glycoproteins are molecules where proteins and carbohydrates are joined together, while glycolipids are molecules where carbohydrates and lipid-containing substances are joined together. And, of course, you will be familiar with molecules that have a combination of lipids and proteins (lipoproteins) – namely, cholesterol in the form of LDL (low density lipoprotein) and HDL (high density lipoprotein) known as “bad” and “good” cholesterol respectively.

How much protein do I need?

Probably less than you would imagine. Opinions differ from authority to authority, but Professor T Colin Campbell, an expert in the field co-author of The China Study, suggests that calories derived from protein should ideally represent around 8-10% of total daily calorie (kcal) intake. So, for instance, if your daily calorie intake is 2000 calories, this would mean between 160 and 200 calories from protein. And since a gram of protein has 4 kcal of energy, this would be 40-50 grams of protein. Again, as a general rule, most authorities recommend we consume around 0.75 grams of protein for each kilogram of lean body weight. So, if you weigh 60 kilograms, this would imply that you need 45 grams (or 180 kcal) of protein a day. I will cover this subject in more detail in future articles – particularly whether protein intake has to be increased when you increase your levels of physical exercise.

What about protein-deficiency?

As far as my research goes, I have never found a single medical recording of protein deficiency within average western populations. The biggest problem is quite the opposite – excessive protein intake. Regarding the traditional and misinformed idea that people eating an exclusively plant-based diet should be very careful about combining proteins in order to get the right balance of essential amino acids, this is covered in my video The Protein Combining Myth – A Rat’s Tale.

COMPARISON OF PROTEIN CONTENT IN ANIMAL AND PLANT FOODS

For those of you who are making the transition from animal foods to plant foods, the following may well encourage you to ignore the ill-informed warnings about protein deficiency – especially in light of the fact that the greatest danger related to protein is over- not under-consumption.

To show how easy it is to get more than enough protein from plants, the following is a list of the foods and drinks taken from my diary three days ago. You will see that I consumed only 1420 kcal on this particular day, whilst on normal days my calorie intake would be between 2000 and 2500 kcal:

The above foods contained a total of 51.2 grams of protein, which represented 12% of total calories (fats made up 21% and carbohydrates 66%). I chose this day as an example because of the relatively low intake of calories. Normally, even with my usual macronutrient ratios (protein 10%/fat 20%/carbohydrate 70%), my protein intake from plant foods is more than necessary for optimal health and energy levels.

THE DANGERS OF TOO MUCH (ANIMAL) PROTEIN IN THE DIET

Kidney Disease

Most people don’t realise that high animal protein intake and kidney disease have been clearly linked for over 100 years (1., 2.). It’s one of the oldest known nutrition links and it has been proven repeatedly that if you take animals with reduced kidney function and give them extra amounts of protein, there is a significant acceleration in the decline of their kidney function. Research has also shown a relationship between increased protein consumption and increased development of kidney cancer. And the relationship between kidney cancer and animal protein consumption is about as strong as any other nutrition cancer linkage. This is why, for a long time, a recommendation for kidney health has been to reduce protein intake.

Cardiovascular Disease

Dr Thomas Campbell mentions a 2016 study (3.) which shows that “among two very large American study populations (female nurses and male health professionals), those that consumed the most animal protein compared to plant protein had a higher risk of death, particularly cardiovascular disease. Researchers found that when 3% of energy from plant protein was substituted for an equivalent amount of processed red meat protein, there was a 34% lower risk of death.

These findings are even more impressive when you consider the fact that researchers controlled for age, intake of different types of fat, total energy intake, glycemic index, and intake of whole grains, fiber, fruits and vegetables, smoking, body mass index, vitamin use, physical activity, alcohol intake, history of high blood pressure. In other words, they statistically eliminated many of the beneficial components of plant-based diets to try to isolate the sole effect of dietary protein and still found an effect. When data was adjusted only for age, total energy and fat intake, those consuming the most plant protein were found to have 33% reduced risk of death, 40% reduced risk of cardiovascular death, and 28% reduced risk of cancer death.

This is even more remarkable given the meat-centered diets that study subjects were consuming. Researchers divided the population into groups based on the amount of protein consumed. Even those consuming the most plant-protein consumed almost 60% more animal protein than they did plant protein. None of these groups were consuming anything remotely similar to the whole-food plant-based diet that has been shown to halt or reverse advanced heart disease, diabetes, and early stage prostate cancer.”

Osteoporosis

Can protein have a detrimental effect on bone? Optimal amounts of protein are not only beneficial but essential for bone health since they improve bone mass – as long as sufficient calcium is also in the diet – and thus reduce potential fractures. However, too much dietary protein can have a detrimental effect on bone – that is if protein (in meat, fish and dairy products) is consumed well in excess of bodily needs. This is because excess protein will increase the acidity of bodily fluids and compartments. The knock-on effect of this is that, over an extended period of time, the alkaline minerals (including calcium and phosphorus) will leach from the bones in an attempt to recreate the ideal state of pH homeostasis. During this process some of this calcium released into the bloodstream will be lost in the urine. This situation is further complicated by factors such as the acid/base status of other foods in the diet, the source of the proteins consumed, and the amount of overall calcium intake.

SAD (Stand American Diets) or modern western diets increase the risk of osteoporosis and associated fractures (4.) because they are so high in animal proteins – affecting the pH balance as indicated above. Not all proteins are equal in relation to the effect they have on bone. Meat, fish and eggs are thought to be particularly linked to increased urinary excretion of calcium because they are particularly acid-forming in their effects on the body. However, consuming alkaline plant-based foods (which will still contain protein) has a decreasing effect on the amount of calcium excreted as urine. Another factor is the calcium-potassium balance: being found mainly in fruits and vegetables, potassium has an additional alkalising effect, thereby reducing calcium excretion and maintaining bone health. Thus, it is not just a matter of reducing the amount of protein consumed, but ensuring that the appropriate sources and amounts of proteins are balanced with increased fruit and vegetable consumption.

References

1. Robertson, W. G. Miner Electrolyte Metab., 13: 228-234, 1987.

2. Robertson, W. G. et al. Chron. Dis., 32: 469-476, 1979.

3. Song M, Fung T, Hu FB, et al.Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Intern Med 2016.

4. Sellmeyer DE , Stone KL , Sebastian A , Cummings SR. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition [01 Jan 2001, 73(1):118-122]. A high ratio of dietary animal to vegetable protein increases the rate of bone loss and the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group.

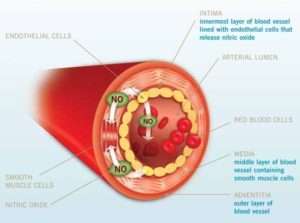

When we eat vegetables “…[w]hat you are doing is you are bathing that cauldron of oxidation inflammation all day long with nature’s most powerful anti-oxidant” – nitric oxide, produced by the endothelial cells within our blood vessels. And it is the green leafy vegetables that he considers to be our best source of nitric oxide-producing foods.

When we eat vegetables “…[w]hat you are doing is you are bathing that cauldron of oxidation inflammation all day long with nature’s most powerful anti-oxidant” – nitric oxide, produced by the endothelial cells within our blood vessels. And it is the green leafy vegetables that he considers to be our best source of nitric oxide-producing foods.