Diverticulitis is a very unpleasant and potentially lethal condition which is increasingly afflicting populations eating the modern Western diet. This blog will look in some detail at its symptoms, causes and history, as well as potential ways in which you can avoid allowing this often hidden-until-too-late condition to creep up on you.

N.B. THIS BLOG CONTAINS SOME GRAPHIC IMAGES.

What are the symptoms of diverticulitis?

The really dangerous thing about this disease is that there can be no symptoms at all until you drop dead. Indeed, it’s reported 1 that nine out of ten people who die of diverticulitis did so without ever even knowing they had it!

Although it can be an asymptomatic disease, there are a range of symptoms that may appear 2 3 , including:

- cramping

- bloating

- abdominal pain, normally on the left side (ranging from slight to excruciating)

- fever

- nausea

- vomiting

- chills

- constipation

- abscesses (the formation of puss)

- fistula 4

- intestinal perforation (the formation of a hole in the wall of the colon)

- sepsis 5

What is diverticulitis?

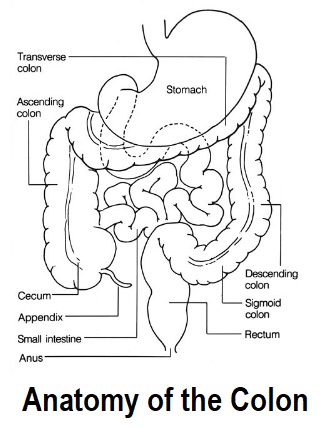

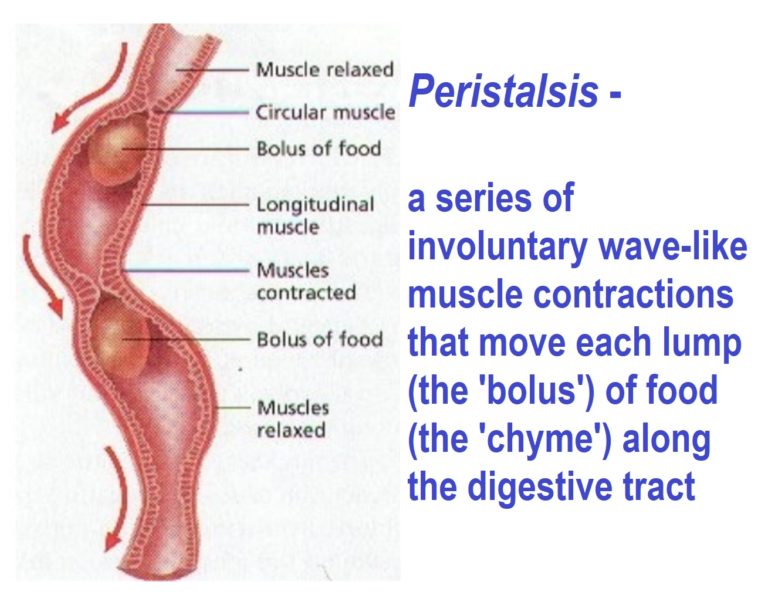

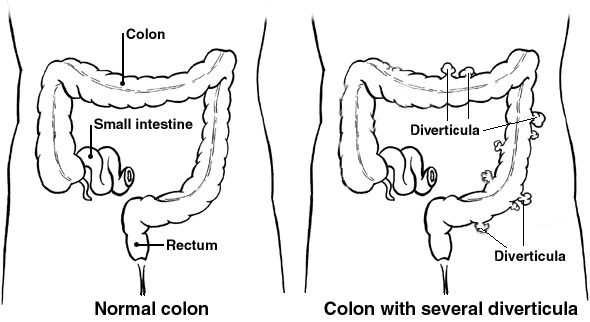

The clue is in the word itself – the Latin word dīverticulum means turn aside or divert. This diversion is exactly what can happen to some of the food (called chyme) as it passes through the intestines (usually in the colon – also known as the bowel), the muscular walls of which are “diverted” outwards into the abdomen. Peristalsis is a process where the muscles of the intestinal walls contract and relax so that the chyme gradually gets pushed along to the anus and out of the body.

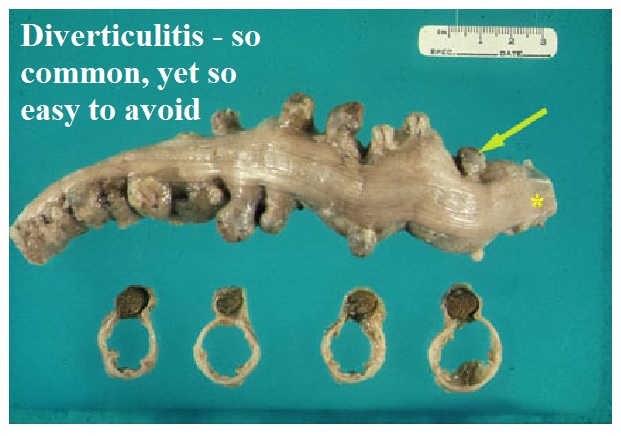

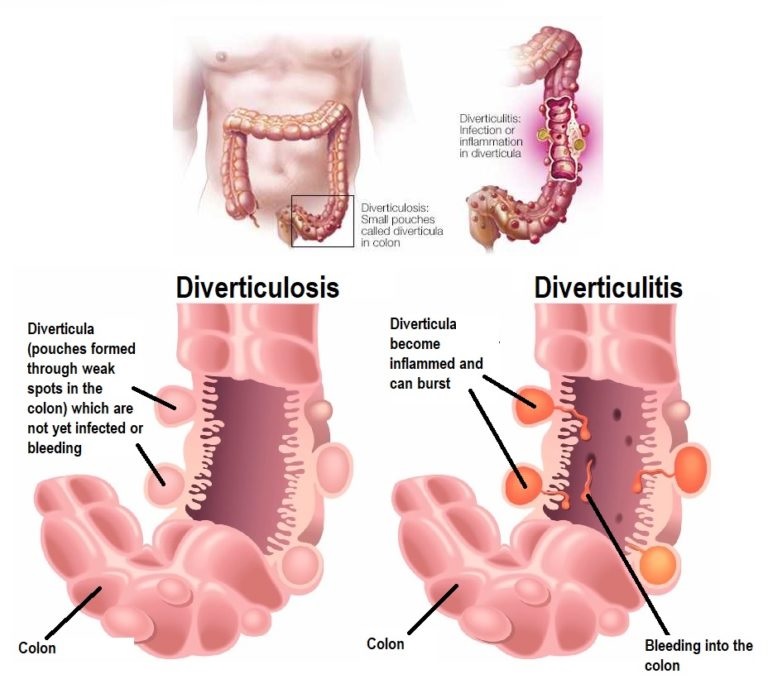

If weak spots are formed in the outer layer of the intestinal wall, the muscles can push outwards laterally, forming pouches or diverticula (diverticulosis). Although the plural is “diverticuli”, many authorities still use “diverticula” for singular and plural. These diverticula can then become inflamed, infected, and start bleeding (diverticulitis). The greatest danger is that infected diverticula will eventually burst, seeping intestinal contents into the bloodstream. This can lead to sudden death.

It’s obvious, then, that diverticulosis occurs first. This condition is usually completely unnoticed and most people never know they have it unless it’s found on a routine colonoscopy. Diverticulitis comes next, and it’s the reason people end up in hospital. It’s reported that 10-25% of individuals with diverticular disease end up developing symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, irregular bowel movements, bleeding, or signs of infection. 6 7

Doctors often use the analogy of an over-inflated inner tube poking out through the wall of a tyre. Similarly, increased internal pressure can force the gut to balloon out through weak spots in the intestinal wall. The results are pretty obvious and rather unpleasant:

If the pressure builds up so much and the diverticula rupture, intestinal contents can be pushed into the abdomen and end up in the blood stream. 8

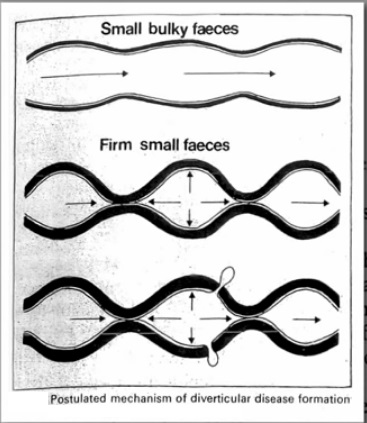

The reason internal pressure can increase so much within the intestines (usually in the colon) is related to the type and quantity of food (chyme) that’s passing through. Continuing the inner tube for intestine analogy – imagine your fingers doing the peristalsis movement and squeezing along a lump of soft mashed potato inside the tube. Should be pretty easy. However, replace the mashed potato with thick gooey molasses and it would be much harder to squeeze it along, resulting in increased internal pressure. If, over a long period of time, your colon is having to squeeze small and compacted lumps, rather than gently contract and dilate around large and soft lumps, damage is pretty inevitable. 9

Most diverticula are not particularly large – around 1-2 centimetres in diameter – but, nevertheless, even at this size they can be big enough to cause symptoms and complications in some people. 10

Dietary fibre & diverticulitis

Just as in the previous blog on constipation 11 , it comes down to the amount of fibre in your diet – too little, and our faeces become small and firm. The same thing is happening within our intestines. If there’s not enough ‘bulk’, the intestines have to squeeze really hard to move the chyme along, and this pressure buildup can force out those bulges and eventually lead to the colon literally rupturing itself.

Just as in the previous blog on constipation 11 , it comes down to the amount of fibre in your diet – too little, and our faeces become small and firm. The same thing is happening within our intestines. If there’s not enough ‘bulk’, the intestines have to squeeze really hard to move the chyme along, and this pressure buildup can force out those bulges and eventually lead to the colon literally rupturing itself.

High-fibre diets make for larger and easier movements through the colon. Plant-based diets contribute a considerable range of intestinal health benefits: adding huge amounts of natural prebiotics and probiotics that permit the gut bacteria (the microbiome) to do their magic: providing anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, anti-obesity and blood sugar control effects; reducing the risk of stroke, high cholesterol and heart disease; helping to prevent hiatal hernia, brain loss, kidney stones, COPD, Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes; aiding weight loss; improving immunity, and ultimately increasing healthy longevity 12 . That our bodies are able to produce sufficient nitric oxide (a powerful antioxidant) is another factor that is of vital importance to the maintenance of health; and, as previous blogs have considered 13 14 , the quality and quantity of plant foods within our diet dictates the type of microbiome inhabiting all parts of our bodies – from our mouths and intestines to our bladder.

I came across a nice Australian site which stated the following: “We evolved in tandem with our gut microbiome, the bacteria and other microbes that inhabit our gut. They are just as much a part of our digestive system as our own cells. They feed on dietary components that are not absorbed in the small intestine, such as dietary fibre and resistant starch. The microbiome pays its fare by providing us with energy and nutrients that would otherwise have been lost. The large bowel or colon is essentially a fermentation vat. This explains the gas.” 15 It’s always good to see that on the other side of the planet, these WFPB websites are quoting the likes of Drs McDougall, Greger, Popper and Klaper.

Low-fibre diets are not the only risk factor for diverticulitis. Additional contributing factors include smoking, being obese, and eating a diet which is high in red meat and animal fat. One study on meat intake and risk of diverticulitis in men, concluded: “Red meat intake, particularly unprocessed red meat, was associated with an increased risk of diverticulitis.” 16

This is backed up by a 2017 study:

“During 894,468 person years of follow-up, we identified 1063 incident cases of diverticulitis….The association between dietary patterns and diverticulitis was predominantly attributable to intake of fiber and red meat.” 17

The modern Western diet contains high levels of animal-based and processed foods. Whilst it’s obvious that animal foods are completely devoid of fibre, some people need to be gently reminded that most processed foods are also very fibre-poor, with most fibre being stripped out during the manufacturing process. 18

Diverticulitis diagnosis

Medical advice should always be sought if you have any symptoms of diverticulitis. Most diagnoses are during an acute attack of abdominal pain.

Medical advice should always be sought if you have any symptoms of diverticulitis. Most diagnoses are during an acute attack of abdominal pain.

Your doctor will normally want to give you a physical examination (checking abdominal tenderness) in order to establish the cause of the pain – and there can be a wide range of causes other than diverticulitis.

Women would also normally have a pelvic examination to rule out pelvic disease. After this, the following are possible diagnostic tests:

- blood and urine tests (checking for signs of infection)

- pregnancy test for women of childbearing age (ruling out pregnancy as a cause of abdominal pain)

- liver enzyme test (ruling out liver-related causes of abdominal pain)

- stool test (ruling out infection in patients with diarrhoea)

- CT scan (identifying inflamed/infected pouches and to confirm a diagnosis of diverticulitis)

Diverticulitis treatment

The severity of symptoms will determined the treatment. There are two broad classifications used: uncomplicated diverticulitis (usually mild symptoms treated at home) and complicated diverticulitis (usually severe symptoms treated at hospital):

- uncomplicated diverticulitis

- antibiotics to fight any detected bacterial infection

- a liquid diet for a few days until intestines heal naturally

- when symptoms improve, gradually add solid food to the diet

- over-the-counter pain relief

- complicated diverticulitis

- intravenous antibiotics

- a tube inserted to drain away any abdominal abscess (if formed)

- surgery – this would normally be needed if:

- certain complications occurred, such as:

- bowel abscess

- fistula

- obstruction

- puncture (perforation) in the colon wall

- you have a history of multiple episodes of uncomplicated diverticulitis (flare-ups – see below)

- you have a weakened immune system

- certain complications occurred, such as:

Acute flare-ups are not uncommon. It’s reported 19 that 20% of people with diverticula develop a bout of diverticulitis at some stage in their lives. Best advice – eat lots of fibre and keep hydrated so that you can avoid them developing in the first place.

Two types of surgery for diverticulitis

The two main types of surgery involved with diverticulitis are:

- primary bowel resection (removing diseased intestinal sections and reconnecting healthy sections)

- bowel resection with colostomy (when inflammation has been too severe to connect the colon to the rectum, a colostomy will be the option. This involves making an opening in your abdominal wall and connecting it to the still-healthy part of the colon. Waste then passes through the opening into a bag. It’s possible in some cases that the inflammation will reduce and the colostomy can be reversed and the bowel reconnected)

A colonoscopy may be recommended at no less than six weeks after recovering from diverticulitis, particularly if no test was done in the previous year. This might be done in order to exclude any cancer. Some authorities consider 20 that there is no direct link between diverticular disease and colon or rectal cancer. Naturally, a colonoscopy cannot be risked during a diverticulitis attack.

When is eating fibre & a WFPB diet not recommended?

When there’s a flare-up of diverticular disease, especially when hospitalisation was required, it’s generally recommended that a low fibre/liquid-like diet is used as a short-term intervention. Primarily advised as a means of managing gut motility and acute pain, this period of so-called “bowel rest” usually involves abstaining from all solid foods for 2-3 days and consuming only a clear liquid diet, with water or other clear beverages usually being all that’s advised. Once the symptoms have disappeared (that is, when acute pain has subsided) and, of course, under the advice of their doctor, the patient would then be advised to transition to a high-fibre plant diet – ideally of the non-SOS WFPB type.

“An absolute must in treating acute diverticulitis is a high-fibre diet if patients wish to prevent complications and recurrences of disease.” 18

Can diverticulitis be reversed by diet?

Once you’ve been diagnosed with diverticulitis, you are strongly recommended to always liaise with your doctor about any dietary changes. However, to avoid recurrence of symptoms, there is little doubt that reducing the pressure within your intestinal tract is key. This is best achieved through eating a diet high in fibre and ensuring you are always fully hydrated.

How much water and fibre is enough? This is a well-debated topic, and was covered in the previous blog 21 , but my research shows that a person eating a balanced WFPB diet is likely to consume up to 100 grams of fibre daily. This is definitely a healthy level. One UK study suggested 22 that for every 5 gram increase in fibre consumed each day, the result was a 15% reduction in disease risk. The same study found that some whole plant fibre sources were especially protective against the disease, namely whole grains and fruits.

How much water and fibre is enough? This is a well-debated topic, and was covered in the previous blog 21 , but my research shows that a person eating a balanced WFPB diet is likely to consume up to 100 grams of fibre daily. This is definitely a healthy level. One UK study suggested 22 that for every 5 gram increase in fibre consumed each day, the result was a 15% reduction in disease risk. The same study found that some whole plant fibre sources were especially protective against the disease, namely whole grains and fruits.

However, if a person chooses not to eat an exclusively WFPB diet, it’s generally advised that over 30 grams of fibre is the lower recommended limit. Personally, I would always suggest that WFPB is the way to go. Best be safe than sorry with something that can kill you quickly without you even knowing you had it in the first place.

In terms of daily liquid (ideally water, or black/green tea) consumption, a minimum of around 7 cups (1.75 litres) of water for women and ll cups (2.75 litres) for men is recommended. Plant foods contain mostly water, and so this will add to liquid intake to make it up to the WHO recommendation of 11 cups (2.75 litres) for women and 15 cups (3.75 litres) for men. 23

It’s been shown 2 that even eating just a standard vegetarian diet (with a high intake of dietary fibre compared with the standard meat-based Western diet), is associated with lowering the risk of getting the disease in the first place, of being admitted to hospital, and of dying from the disease. How much more for a WFPB diet with its higher fibre content? Other studies have shown similar results, stating: “Consuming a vegetarian diet and a high intake of dietary fibre were both associated with a lower risk of admission to hospital or death from diverticular disease.” 24

Dr John McDougall considers that it’s certainly worth changing to a high-fibre diet in order to relieve symptoms and prevent further diverticuli: “Contrary to what was once popular opinion, the addition of fibers in the form of brans or high fiber foods has relieved symptoms in 90% of cases of severe colon disease, even with recurrent pain and bleeding. A high fiber diet will also decrease the likelihood of developing new diverticuli. The diverticuli already formed are permanent herniations of the colon, and will not disappear except by surgical removal, which is rarely indicated.” 25

In the following short video, Dr McDougall also reassures us that the bleeding and infection within diverticuli can, in most cases, disappear by making simple dietary changes. The diverticuli themselves remain, although he considers that they would no longer be a problem, so long as a high-fibre diet is maintained.

Diverticulitis rises as fruit & veg consumption drops

Major studies have shown 6 26 beyond any doubt that the risk of developing diverticular disease goes down as fruit and vegetable consumption goes up – and, of course, vise versa. These studies produced the following results:

- increased diverticular disease is associated with consumption of:

- beef

- lamb

- pork

- processed meats

- cookies

- potato/corn crisps (chips in the US)

- French fries (chips in the UK!), and

- white bread

- physical activity (running/jogging) reduces disease risk

- decreased diverticular disease is associated with

- increased fibre intake

- the strongest correlation of disease reduction is associated with consumption of:

- fruit, and

- cereal fibre

- consumption of all vegetable fibre also reduces disease risk

A further study 7 looked at the effects of using a high-fibre diet in the cases of 100 patients who had been previously diagnosed with acute diverticulitis. After 5-7 years on this diet, 91% of the patients remained completely symptom-free. The authors pointed out that the following respected organisations endorse and encourage the use of a high-fibre diet to prevent diverticular disease:

- American College of Gastroenterology 27

- European Association for Endoscopic Surgery 28

- American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons 29

- World Gastroenterology Organisation 30

Can you eat nuts and seeds if you have diverticulitis?

The usual medical advice around people who have had diverticulitis is that they should avoid eating nuts, seeds, corn, and popcorn. Indeed, some doctors advise that everyone should avoid these foods as a means of avoiding the disease. However, there are at least two recent studies that have blown this unfounded advice out of the water.

A 2009 study 10 stated: “Without any good evidence, certain foodstuffs such as nuts, seeds, popcorn, and corn have long been implicated in the development of diverticulitis and are often advised against by physicians. They were thought to provoke diverticulitis or diverticular bleeding by causing luminal trauma. In a large prospective study of men without known diverticular disease, Strate et al found 31 that nut, corn, and popcorn consumption did not increase the risk of diverticulosis, diverticulitis, or diverticular bleeding.”

A 2012 study 32 stated: “Residue refers to any indigestible food substance that remains in the intestinal tract and contributes to stool bulk. Historically, low-residue diets have been recommended for diverticulosis because of a concern that indigestible nuts, seeds, corn, and popcorn could enter, block, or irritate a diverticulum and result in diverticulitis and possibly increase the risk of perforation. To date, there is no evidence supporting such a practice. In contrast, dietary fiber supplementation has been advocated to prevent diverticula formation and recurrence of symptomatic diverticulosis, although this is based mostly on low-quality observational studies.”

Whilst further research is useful, any advice to avoid nuts & seeds does not appear to be based on anything but unfounded conjecture. And, as shown in the 12-year long Seventh Day Adventist Study published in 2001, vegans who didn’t eat any nuts and seeds didn’t live as long as those vegans who did. This is because of the essential fats that nuts and seeds contain – allowing effective absorption of the phytochemicals and anti-oxidants that both groups are eating 33 34

How common is diverticulitis?

“Diverticular disease [including diverticulitis] is the most common intestinal disorder.” 35

One study states: “In industrialized nations, diverticular disease affects up to 70% of individuals by 60 years of age, with symptoms that can range from mild gastrointestinal disturbance to incapacitating pain.” 36

Is diverticulitis age-related?

Whilst it’s been conventionally thought that it is an inevitable age-related condition – with the theory being that the intestinal walls tend to weaken as the years and decades pass – this theory can be shown to be untrue. Back in 1907, guess how many cases were recorded? 25! 36 That’s not 25% of the population, but 25 individual cases had been reported in the medical literature. And, as you can see from the graphic photograph above, any autopsy would have had little difficulty in missing diverticulitis if it had been present.

“Development of diverticular disease is not an inevitable part of growing older. The colons of people living in underdeveloped countries show a virtual absence of diverticular disease. Healthy, low, pressures in the colon happen when the diet is high in starches, vegetables, and fruits, with their generous content of fiber.” 25

Even in 1916, a study 37 reported that diverticulitis was still not sufficiently documented as a morbid disease in medical literature for it to merit medical recognition.

Diverticulitis – a late 20th Century disease

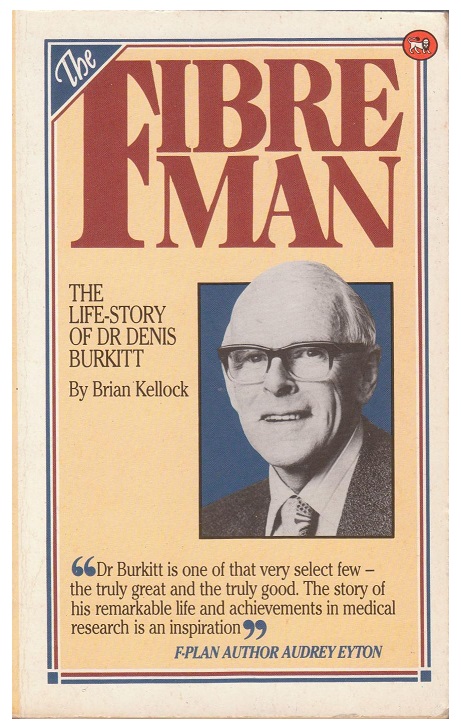

But in a 1971 study, by the WFPB pioneer Denis Burkitt and his team 38 , it was already recognised as the most common intestinal disease in the US population.

But in a 1971 study, by the WFPB pioneer Denis Burkitt and his team 38 , it was already recognised as the most common intestinal disease in the US population.

How could this have happened so quickly?

Denis Burkitt showed incredible insight by pointing out that it was most probably down to the fact that even by the 1970’s the Western diet had become low in fibre and high in animal products, processed and highly refined foods. Indeed, it took just half a century from the introduction of rolling milling of flour (which greatly reduced the natural fibre content) in the late 1800’s for diverticulitis to become common in the UK by the 1920’s.

Since then, things have gone from bad to worse.

A number of the first researchers to study diverticulitis nicknamed it a “20th century problem” and a “disease of Western civilisation.” 6

Denis Burkitt’s team back in the 1970’s included in their report 38 a simple diagram which they thought explained the process by which diverticula are formed:

It’s probably no surprise that the US and European populations have the highest rates of diverticular disease in the world, whilst it is rarely found in developing countries before, that is, they adopt the Western diet. 39 7

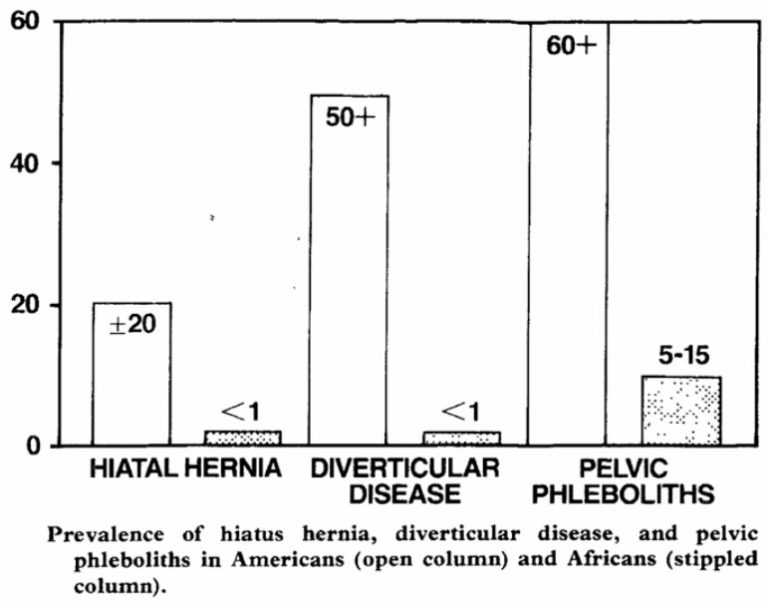

A 1985 study 40 , again by Denis Burkitt, compared Americans and Africans to see if there were differences in their rates of diverticulitis and other intestinal diseases related to low-fibre diets – namely, hiatus hernia and pelvic phleboliths 41 . As Dr Greger pointed out in a video on this subject 42 , Burkitt found a huge difference in diverticulitis rates between the Africans eating the high-fibre diet (less than 1% of the population) and the Americans eating the low-fibre diet (more than 50% of the population):

Your poo can give a clue

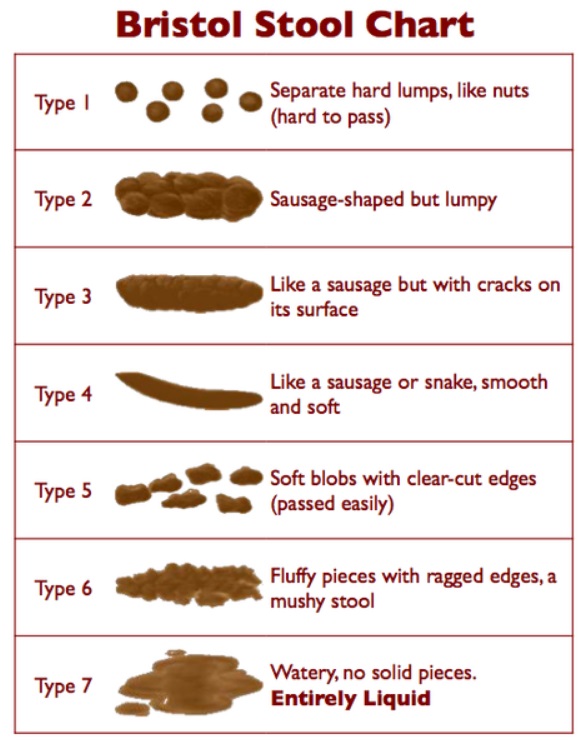

This might not be the most tasteful subject, but you can tell a lot about the likely state of your intestines by checking on what your poo (stool or faeces) looks like. If you’re regularly constipated, and diverticula have already formed in the colon, stagnant faecal matter ends up clogged in the diverticula “bubbles”. 39 This can, in turn, trigger inflammation of the intestinal wall, resulting in the above-mentioned symptoms. The following chart is one of the standard charts used to get clues from your poos:

The Bristol Stool Chart provides a graphic version of various stool samples.

Developed by Dr. Ken Heaton from the University of Bristol in the late 1990’s, it’s used primarily as a clinical communication aid in categorising stool types 43 .

It’s only meant to be an unofficial guide, but does allow us to get a general idea of the classification of our poo, providing, thereby, a reasonably good indicator of both the diet we’re eating and the likely state of our intestines.

- types 1 and 2 are typical of a constipated individual

- type 3 is borderline normal

- type 4 is the “gold standard for the perfect stool”

- type 5 is heading in the direction of diarrhoea

- types 6 and 7 reflect an individual in diarrhoea distress

If you want to delve deeper into the subject of bowel movements and constipation, Dustin Rudolph, PharmD has written a useful article. 44

It’s worth repeating that the balance of gut bacteria can be altered by chronic constipation and eating a low-fibre diet. Rather than a colon full of “good” (healthy) bacteria, there’s an increase in “bad” (infectious) bacteria that populate the colon. And it’s the presence of the latter bacteria that can further increase the chances of an infection developing.

Low-fibre diets do NOT cause diverticulitis!

Just to confuse the issue, a 2012 North Carolina study 45 came up with completely different conclusions than everything else that’s been said above about diverticulitis (and, of course, constipation) being powerfully linked to low-fibre diets. The study concluded:

“In our cross-sectional, colonoscopy-based study, neither constipation nor a low-fiber diet was associated with an increased risk of diverticulosis.”

By understanding the reason that they found no association, we can learn something about the quantity of fibre necessary to make a significant difference to your risk of developing chronic constipation and/or diverticulitis, plus we can learn a lot about how clinical trials can come up with misleading information.

In this study, they took two groups and carefully ensured that one group received only 8 grams of fibre a day while the other group received 25 grams of fibre a day. When they compared the results, there was no significant difference in the rates of diverticulosis and, thus they announced to the world that we do not need to bother eating a high-fibre diet in order to maintain good gut health.

The story was taken up all over the world, with headlines like:

“Diets high in fiber won’t protect against diverticulosis, study finds.“46 47

“High-fibre diet may not protect against diverticulosis.” 48

“Paleo Diet: More Evidence That Fiber is Not A Good Thing.” 49

And not only did the Paleo crowd get involved and believe the study findings, even medical journals jumped on the band wagon, quoting the conclusions of the above study:

“Diverticulosis and dietary fiber: rethinking the relationship…A high-fiber diet does not protect against asymptomatic diverticulosis.” 50

So, what’s going on here?

Firstly, good news about bad habits is always attractive for those who want to justify their own bad dietary habits – tucking into a juicy beefburger and fries with impunity, rather than having to worry about eating all that rabbit food!

However, the fatal flaw in the study was identified pretty quickly by other studies, including the following:

“Most importantly, how this study is interpreted is limited by the overall low-fiber intake within the study population. Although the authors performed analyses stratified by fiber intake and found no significant difference between those in the lowest (2.5–10.1 g) and highest quartiles (18.4–50.3 g) of fiber intake, few patients in the uppermost quartile had a true high fiber intake. An analysis reflecting clinical recommendations of high-fiber (>25 g) vs low-fiber (<14 g) diets may have yielded different results.” 51

To clarify just what this flaw of the study was, Dr Greger 52 drew an excellent analogy with early vitamin C studies. It takes around 10 mg of vitamin C a day to avoid developing scurvy 53 .

To clarify just what this flaw of the study was, Dr Greger 52 drew an excellent analogy with early vitamin C studies. It takes around 10 mg of vitamin C a day to avoid developing scurvy 53 .

Back in the 1700’s, James Lind 54 wondered if scurvy in sailors could be avoided if they were given wedges of lemon each day. So he tested his theory. One group were given one wedge of lemon, and the other group were given three wedges of lemon a day. He found no difference at all between the groups, and the same ratio came down with scurvy.

So, did this prove that low vitamin C levels are not associated with the development of scurvy? Of course not. In order to prevent scurvy, it’s necessary to ingest at least 10 mg of vitamin C, and a single wedge of lemon only has around 2 mg. So, even with three wedges of lemon, you’re still only getting around 6 mg.

See the analogy?

The group eating the highest amount of fibre in the above North Caroline study 45 were only eating around 25 grams of fibre a day, which is less than the US minimum recommended daily allowance of around 32 grams. As Dr Greger says: “They didn’t even make the minimum. So they compared one fiber-deficient diet to another fiber-deficient diet—no wonder there was no difference in diverticulosis rates.”

Whenever looking at any study results that appear “too good to be true”, it’s always worth checking on what was compared with what – after all, even a McDonald’s Big Breakfast is healthy when compared with…smoking tobacco or inhaling asbestos!

Final thoughts

As with many things in life, simple is best. The best form of cure for diverticular disease is prevention. And the best form of prevention is undoubtedly provided by eating a high-fibre diet, keeping well-hydrated, and getting plenty of regular daily exercise.

I can’t really think of a better way of ending than by quoting a closing comment by Dustin Rudolph, PharmD, writing for T Colin Campbell’s Center for Nutrition Studies (CNS), made at the end of his article on diverticular disease:

“Eat plants. Get lots of fiber. Live happy. And avoid doctors and pharmacists if at all possible by adopting a whole food, plant-based lifestyle. Your body will thank you for many years to come.” 18

References & Notes

- J Chapman, M Davies, B Wolff, E Dozois, D Tessier, J Harrington, D Larson. Complicated diverticulitis: is it time to rethink the rules? Ann Surg. 2005 Oct;242(4):576-81; discussion 581-3. [↩]

- Spiller, R. C. (2015). Changing views on diverticular disease: impact of aging, obesity, diet, and microbiota. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 27(3), 305-312. [↩] [↩]

- Health Navigator New Zealand. Diverticular disease and diverticulitis. Retrieved from https://www.healthnavigator.org .nz/health-a-z/d/diverticular-disease-diverticulitis/ [↩]

- A fistula, in this case, is an abnormal passage between a hollow or tubular organ and the body surface, or between two hollow or tubular organs. In this case, it is more commonly between the intestine and the bladder. [↩]

- Diverticulitis: Causes, Symptoms & Treatment. By Alina Bradford. June 12, 2018. [↩]

- Aldoori W, Ryan-Harshman M. Preventing diverticular disease. Review of recent evidence on high-fibre diets. Can Fam Physician. 2002 Oct;48:1632-7. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Unlu C. Daniels L, et al. A systemic review of high-fibre dietary therapy in diverticular disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:419-427. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- N S Painter. Diverticular disease of the colon. The first of the Western diseases shown to be due to a deficiency of dietary fibre. S Afr Med J. 1982 Jun 26;61(26):1016-20. [↩]

- Painter N, Truelove S, et al. Segmentation and the localization of intraluminal pressure in the human colon, with special reference to the pathogenesis of colonic diverticula. Gastroenterology. 1968;54(Suppl):778-780. [↩]

- Beckham H, Whitlow CB. The Medical and Nonoperative Treatment of Diverticulitis. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:156-160. [↩] [↩]

- Constipation & Plant-Based Diets [↩]

- Nutritionfacts.org. Topic: Fibre. [↩]

- Are Nitrates & Nitrites Bad For Us? [↩]

- Greens: Chewing vs Juicing [↩]

- wholefoodsplantbasedhealth.com: Gut Health. [↩]

- Cao, Y., Strate, L. L., Keeley, B. R., Tam, I., Wu, K., Giovannucci, E. L., & Chan, A. T. (2017). Meat intake and risk of diverticulitis among men. Gut, gutjnl-2016. [↩]

- Gastroenterology. 2017 Apr;152(5):1023-1030.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.038. Epub 2017 Jan 5. Western Dietary Pattern Increases, and Prudent Dietary Pattern Decreases, Risk of Incident Diverticulitis in a Prospective Cohort Study. Strate LL et al. [↩]

- CNS: What Is Diverticular Disease and How to Treat It. By Dustin Rudolph, PharmD. February 14, 2019. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Patient. Diverticula (including Diverticulosis, Diverticular Disease and Diverticulitis). Retrieved from http:// patient.info/health/diverticula-including-diverticulosis-diverticular-disease-and-diverticulitis [↩]

- Mayo Clinic: Patient Care & Health Information Diseases & Conditions: Diverticulitis [↩]

- Constipation & Plant-Based Diets [↩]

- Crowe, F., Appleby, P., Allen, N., & Key, T. (2011). P2-54 Diet and risk of diverticular disease in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC)-Oxford cohort, a prospective study of British vegetarians and non-vegetarians. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 65(Suppl 1), A234-A234. [↩]

- How Many Glasses of Water Should We Drink a Day? Michael Greger M.D. FACLM May 25th, 2015 Volume 24. [↩]

- Diet and risk of diverticular disease in Oxford cohort of European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): prospective study of British vegetarians and non-vegetarians. BMJ 2011; 343 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4131 [↩]

- Dr John McDougall: Diverticular Disease – Diverticulosis & Diverticulitis. [↩] [↩]

- Crowe FL, Balkwill A, et al. Source of dietary fibre and diverticular disease incidence: a prospective study of UK women. Gut. 2014;63:1450-1456. [↩]

- ACG: Diverticulosis and Diverticulitis [↩]

- European Association for Endoscopic Surgery and other Interventional Techniques [↩]

- American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons: Treatment of Sigmoid Diverticulitis (Revised). [↩]

- World Gastroenterology Organisation: Diverticular Disease. [↩]

- Strate L L, Liu Y L, Syngal S, Aldoori W H, Giovannucci E L. Nut, corn, and popcorn consumption and the incidence of diverticular disease. JAMA. 2008;300(8):907–914. [↩]

- Tarleton S, DiBaise JK. Low-residue diet in diverticular disease: putting an end to a myth. Nutr Clin Pract. 2011 Apr;26(2):137-42. [↩]

- Adventist Health Study-1 Publication Database [↩]

- Why Vegans Need Fats And DHA by Joel Fuhrman, M.D. [↩]

- Diverticulosis: When Our Most Common Gut Disorder Hardly Existed. Michael Greger M.D. FACLM July 17th, 2015 Volume 25 [↩]

- J Y Wick. Diverticular disease: eat your fiber! Consult Pharm. 2012 Sep;27(9):613-8. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2012.613. [↩] [↩]

- W H M Telling, O C Gruner. Acquired diverticula, diverticulitis, and peridiverticulitis of the large intestine. Brit J Surg. 4:468-530, 1917. [↩]

- N S Painter, D P Burkitt. Diverticular disease of the colon: a deficiency disease of Western civilization. Br Med J. 1971 May 22;2(5759):450-4. [↩] [↩]

- Boynton W, Floch M. New strategies for the management of diverticular disease: insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6(3):205-213. [↩] [↩]

- D P Burkitt, J L Clements Jr, S B Eaton. Prevalence of diverticular disease, hiatus hernia, and pelvic phleboliths in black and white Americans. Lancet. 1985 Oct 19;2(8460):880-1. [↩]

- Pelvic phleboliths are are round clusters of calcium that develop in the walls of a vein. They can vary in size but are usually around 5 mm across. They most commonly appear in the veins surrounding the pelvis. They can be caused by constipation and straining, which can damage pelvic veins. [↩]

- Diverticulosis: When Our Most Common Gut Disorder Hardly Existed. Michael Greger M.D. FACLM July 17th, 2015 Volume 25. [↩]

- Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997. [↩]

- Dustin Rudolph, PharmD. The Anatomy Of A Bowel Movement (And How To Cure Constipation). August 14, 2013. [↩]

- A F Peery, R S Sandler, D J Ahnen, J A Galanko, A N Holm, A Shaukat, L A Mott, E L Barry, D A Fried, J A Baron. Constipation and a low-fiber diet are not associated with diverticulosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Dec;11(12):1622-7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.033. [↩] [↩]

- ScienceDaily: Diets high in fiber won’t protect against diverticulosis, study finds [↩]

- UHC HealthTalk: Diets high in fiber won’t protect against diverticulosis. January 23, 2012. [↩]

- The Washington Post: High-fibre diet may not protect against diverticulosis. [↩]

- Paleo Diet News: Paleo Diet: More Evidence That Fiber is Not A Good Thing. Posted on February 1, 2012. [↩]

- L L Strate. Diverticulosis and dietary fiber: rethinking the relationship. Gastroenterology. 2012 Feb;142(2):205-7. [↩]

- R E Burgell, J G Muir, P R Gibson. Pathogenesis of colonic diverticulosis: repainting the picture. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Dec;11(12):1628-30. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.046. [↩]

- Does Fiber Really Prevent Diverticulosis? Michael Greger M.D. FACLM July 20th, 2015 Volume 25 [↩]

- Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms include weakness, feeling tired, and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding from the skin may occur. As scurvy worsens there can be poor wound healing, personality changes, and finally death from infection or bleeding. [↩]

- Tröhler U (2003). James Lind and scurvy: 1747 to 1795. [↩]