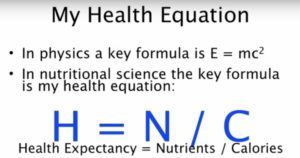

The amount of nutrients, rather than the amount of calories, may determine the nature and intensity of hunger – thus helping to explain the paralleled increases in rates of obesity, chronic disease and fast food consumption.

Dr. Joel Fuhrman and his team undertook a study to discover what differences exist in the experience and perception of hunger before and after participants shifted from their previous usual diet to a high nutrient density diet. The following is a precis of the research interspersed with my comments. Apologies in advance for frequent repetition of key aspects, but the study itself expressed and re-expressed what appeared to be similar points but with subtle variations and additions.

Method

This was a retrospective, non-controlled, descriptive study conducted with 768 participants primarily living in the United States who had changed their dietary habits from a low micronutrient to a high micronutrient diet.

Participants completed a survey rating various dimensions of hunger when on their previous usual diet versus the high micronutrient density diet:

- physical symptoms,

- emotional symptoms, and

- location of hunger sensations in the body

Overview

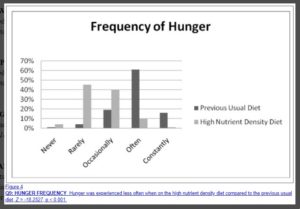

Highly significant differences were found between the two diets:

- Hunger was not an unpleasant experience while on the high nutrient density diet compared with the low nutrient density diet.

- Hunger was well tolerated in the high nutrient density diet and occurred with less frequency even when meals were skipped.

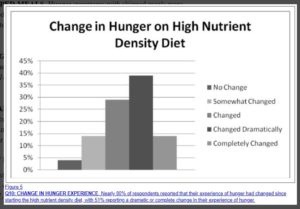

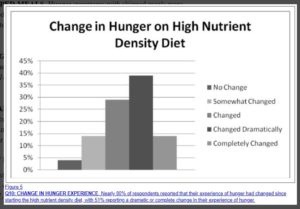

- Nearly 80% of respondents reported that their experience of hunger had changed since starting the high nutrient density diet.

- 51% reported a dramatic or complete change in their experience of hunger from their normal diet to the high nutrient density diet.

Micronutrient density & hunger

A high micronutrient density diet mitigates the unpleasant aspects of the experience of hunger even though it is lower in calories.

- Hunger is one of the major impediments to successful weight loss.

- It’s not simply the caloric content, but more importantly, the micronutrient density of a diet that influences the experience of hunger.

- A high nutrient density diet, after an initial phase of adjustment during which a person experiences “toxic hunger” due to withdrawal from pro-inflammatory foods, can result in a sustainable eating pattern that leads to weight loss and improved health.

- A high nutrient density diet provides benefits for long-term health as well as weight loss.

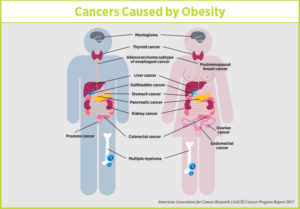

- The results have important implications in the global effort to control rates of obesity and related chronic diseases.

Micronutrient deficiency & food cravings

One of the common barriers to weight loss is the uncomfortable sensation of hunger that drives overeating and makes dieting fail.

The study is based on Dr. Fuhrman’s clinical experience which clearly suggested that enhancing the micronutrient quality of the diet – even in the context of a substantially lower caloric intake – dramatically mitigates the experience of hunger in his patients.

A diet high in micronutrients appears to decrease food cravings and overeating behaviours.

Sensations such as:

- fatigue,

- weakness,

- stomach cramps,

- tremors,

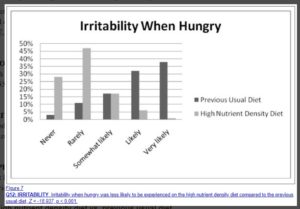

- irritability and headaches,

commonly interpreted as “hunger”, disappear gradually for the majority of people who adopt a high nutrient density diet, and a new, less distressing, sensation (which the researchers label “true” or “throat” hunger) replaces it.

Oxidative stress, toxic metabolites & inflammation

It is well documented [1-4] that a diet low in antioxidant and phytochemical micronutrients leads to heightened oxidative stress and a build-up of toxic metabolites (substances formed in or necessary for metabolism).

It has also been shown [5-10] that a higher intake of nutrient rich plant foods decreases measurable inflammatory by-products.

It is thought that a diet containing an abundance of processed food and low in micronutrient-rich plant foods can create physical symptoms of withdrawal when digestion ceases in between meals.

Toxic hunger

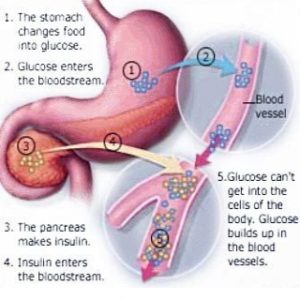

There are two stages of digestion, the anabolic stage which occurs when you are eating and then digesting, and the catabolic stage which begins when you stop eating and your body begins to repair and heal any damage.

The contention is that during the catabolic phase of the digestion and refeeding cycle, when digestive activities cease, these withdrawal symptoms, misperceived as “hunger”, develop from a diet that is inadequate or poor in micronutrients.

These symptoms are called “toxic hunger” by the research team.

Food cravings & dopamine

A “dopaminic high” [11,12] from ingestion of high calorically concentrated sweets and fats has been documented and leads to subsequent craving of these foods.

It is speculated that the discomfort of withdrawal from the toxins mobilised when one tries to refrain from consumption of pro-inflammatory processed foods and animal products may be also be a major contributor to compulsive eating and consequent obesity.

Antioxidants & phytonutrients

Dietary micronutrients such as antioxidants and phytonutrients are required for the body to properly reduce the production and removal of metabolic waste products.

Healthful eating appears to be more effective for long-term weight control because it modifies and diminishes the sensations of withdrawal-related hunger, enabling overweight individuals to be more comfortable even while consuming substantially fewer calories.

Results in charts

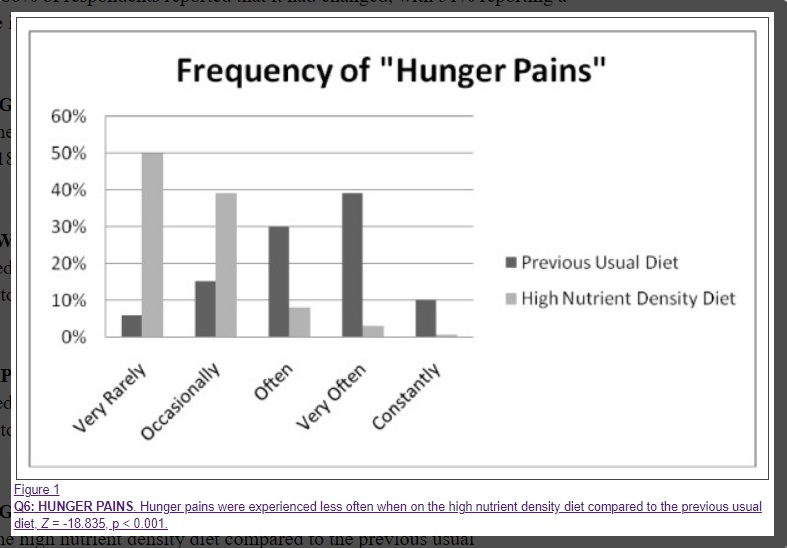

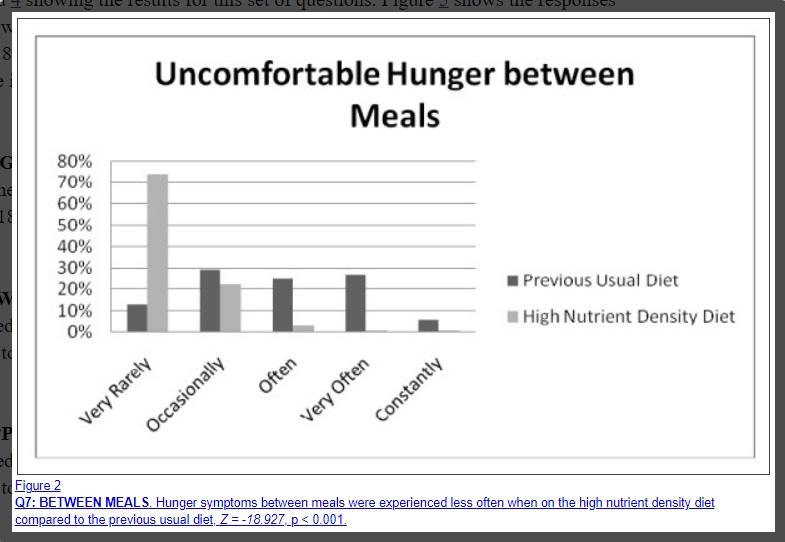

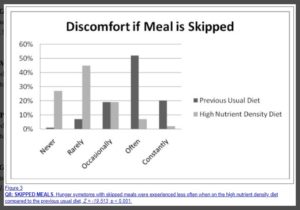

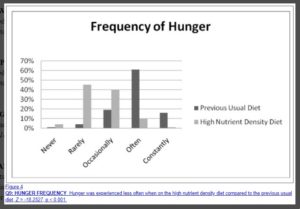

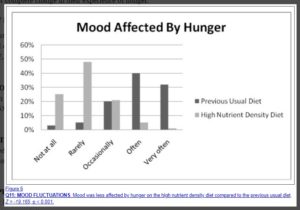

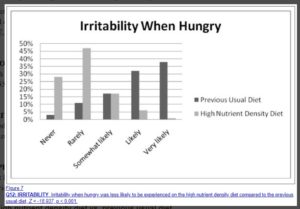

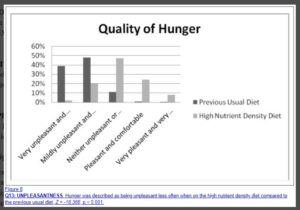

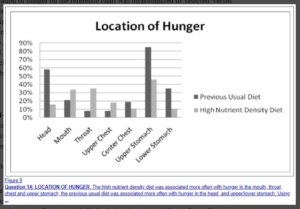

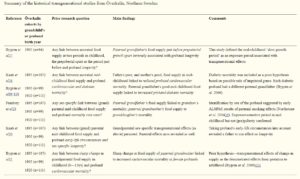

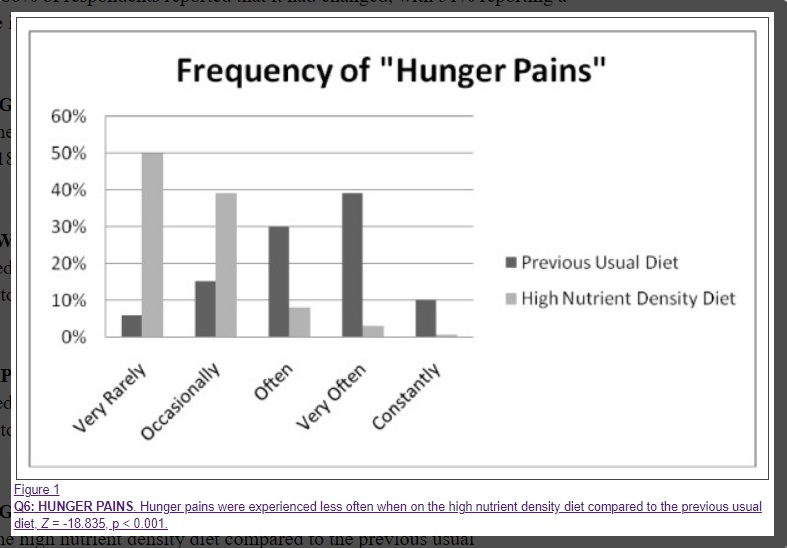

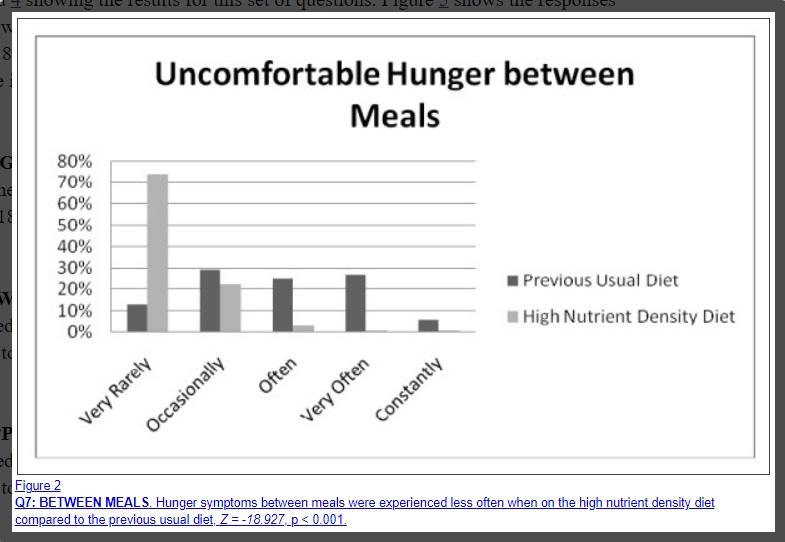

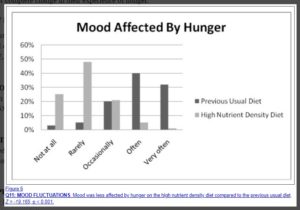

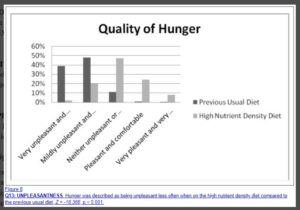

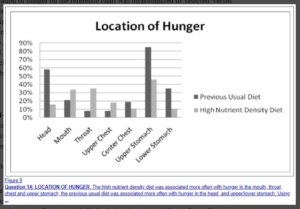

The following charts are pretty self-explanatory, showing significant differences between the experience of hunger when eating either a nutrient-poor or -rich diet:

Frequency of “Hunger Pains”

Uncomfortable Hunger between Meals

Discomfort if Meal is Skipped

Frequency of Hunger

Change in Hunger on High Nutrient Density Diet

Mood Affected by Hunger

Irritability When Hungry

Quality of Hunger

Location of Hunger

Discussion

Society & the cycle of overeating

This study provides important insights into hunger in a society characterised by over-consumption of processed food with an excess of calories and deficiency of micronutrients. Such hunger creates a cycle of overeating leading to obesity and is an obstacle for those who attempt to establish a healthy eating pattern and normal BMI.

- The uncomfortable physical and emotional symptoms of hunger were much less prevalent after a change to the high nutrient density diet.

- Those who are able to make the change to a high nutrient density diet experienced uncomfortable sensations of hunger less often than they experienced on their previous usual diet.

- This may explain the previously reported [18] high levels of compliance and successful weight loss with the high nutrient density diet. Their hunger was less often characterised by classic withdrawal symptoms such as headaches, tremors, stomach cramps, and mood changes. Rather, it was more often felt as a throat sensation that was easily tolerated.

The biochemical processes involved

As soon as the intake, digestion and assimilation of food is complete, the catabolic utilisation of glycogen reserves and fatty acid stores begins. Hunger normally increases in intensity as glycogen stores are diminishing toward the end of glycolysis (the breakdown of glucose by enzymes, thus releasing energy), and should not occur at the start of the catabolic phase when glycolysis begins (see glucose response curve diagram below).

The Glucose Response Curve

Toxic vs real hunger

The contention of the researchers is that the uncomfortable symptoms that drive overeating behaviours early in the catabolic phase should be recognised as withdrawal symptoms from a sub-optimal diet and not true hunger.

After the completion of digestive activity, during catabolism, the mobilisation and elimination of cellular waste products are heightened, thus precipitating symptoms commonly thought to be hunger.

In contrast, true hunger occurs much later when glycogen stores near completion, preventing gluconeogenesis (the utilisation of muscle tissue for needed glucose once glycogen stores have been depleted). True hunger protects lean body mass, but does not fuel fat deposition. It exists to protect lean body mass from utilisation as an energy source.

Support of findings from recent research on the physiology of metabolism

- When a diet is low in dietary antioxidants, phytochemicals and other micronutrients, intra-cellular waste products such as free radicals, advanced glycation end products, lipofuscin, lipid A2E, and others accumulate [9,19].

- Other studies have demonstrated an adverse impact of low-micronutrient foods containing higher amounts of simple carbohydrates, fats and animal products on levels of inflammatory markers, metabolic by-products and oxidative stress in the body [20,21].

- It is well established in the scientific literature that these substances contribute to disease [22-25].

- And that they can be associated with typical withdrawal symptoms, including headaches [26,27].

- Heightened elimination of these waste products may create symptoms that can be experienced similar to withdrawal from drug addiction [28].

- In the absence of an adequate intake of phytochemicals and other micronutrients, cellular detoxification is impaired [29] which elevates cellular free radical activity, priming the body with more substrate to induce withdrawal symptoms when digestion ceases.

When eating relieves uncomfortable symptoms

The theory is that the above uncomfortable symptoms, relieved by eating which halts catabolism and arrests the detoxification process, are widely misperceived as hunger. In a society with an abundance of fast food and high rates of obesity, commonly experienced sensations of hunger may actually be symptoms of withdrawal from a diet that is inadequate in micronutrients.

Such a diet creates an excess of pro-inflammatory metabolic waste products as well as an addiction syndrome.

Food addiction as a clinical condition

- There is growing evidence that food addiction is a clinical pathological condition [30-43].

The results both from this small study and from Dr. Fuhrman’s clinical experience suggest that this addiction is caused by withdrawal symptoms being misread as hunger from pro-inflammatory foods and can be mitigated by consumption of a diet high in anti-inflammatory micronutrients found in vegetables and other micronutrient-rich plant foods.

- Evidence suggests that overweight individuals build up more inflammatory markers and oxidative stress when fed a low nutrient meal compared to normal weight individuals [20,21].

- The heightened inflammatory potential in those with a tendency for obesity is marked by increasing levels of lipid peroxidase (the process by which free radicals “steal” electrons from the lipids in cell membranes, resulting in cell damage) and malondialdehyde (a highly reactive compound that occurs naturally and is a marker for oxidative stress) and reduced activation of hepatic detoxification enzymes (these liver enzymes help neutralise and convert toxins into less harmful byproducts, which can still pose a toxic threat to the body if not removed efficiently).[44].

The vicious cycle

People prone to obesity get more withdrawal/hunger symptoms, preventing them from being comfortable in the non-digestive (catabolic) stage where breakdown and mobilisation of toxins is enhanced.

The resulting uncomfortable symptoms drive them to eat again and over-consume calories. It is a vicious cycle promoting continuous (anabolic) digestion, frequent feedings and increased intake of calories.

Chronically overweight people in the typical American food environment feel “normal” only by eating too frequently or by eating a heavy meal, so that the anabolic process of digestion and assimilation continues right up to the beginning of the next meal. Excess calories are needed in order to feel normal.

- A review of research on companion animals suggested that the introduction of specific micronutrients positively influenced the health status of animals whose natural detoxification systems were compromised, and reduced the accumulation of inflammatory markers [29].

This may explain why those on the high nutrient density diet were able to go for longer periods without feeling “hunger” symptoms.

Relationship between type of foods & hunger intensity/frequency

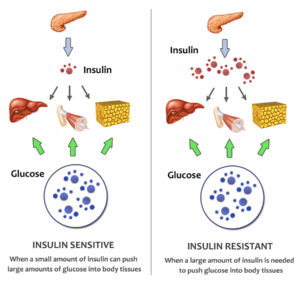

- One theory that has been investigated is the glucostatic theory which links dynamic changes in blood glucose with appetitive sensations [45-48].

- Several studies have explored the relation between the glycaemic index or fibre content of food and satiety, whereas others have examined whether the type or amount of fatty acids, sugars or protein in the diet affect the sense of hunger [49-62].

Results have been inconsistent. This may be due to the unknown variable of micronutrient intake in these studies.

- Some studies have documented a decrease in appetite with ingestion of greater amounts of fibre and/or micronutrients [49,52,56].

- A Canadian study found that fasting and postprandial appetite ratings were reduced in women who were supplemented with multivitamins and minerals [63].

Significance of the findings from this and other similar studies

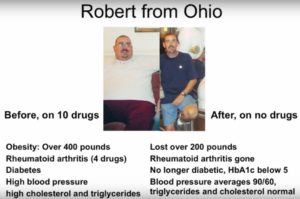

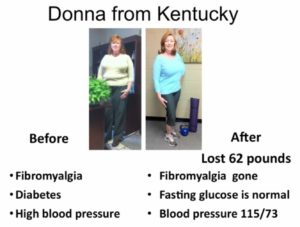

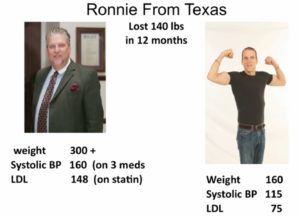

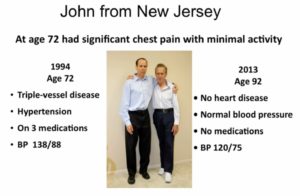

- Highly significant reductions in blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, fasting glucose and body weight have been reported in persons who have made the change to a high micronutrient diet [18].

- There is a vast body of research documenting the protective benefit of a micronutrient-rich diet against cancer and cardiovascular disease [1,8,10,24,25,64-77].

Doctors and obese or chronically ill patients

If clinicians can assure their patients with confidence that they will not experience uncomfortable sensations of hunger after the “detoxification” stage is over, they can keep their patients motivated to withstand the withdrawal symptoms they experience early in the dietary transition.

The outcome will be not only substantial and sustainable weight loss, but prevention of many major chronic diseases in patients.

Future studies

There are limitations in this study, but the number of participants and highly significant test statistics provide leads for future studies that are better controlled and prospective in design. It also provides some important clinical insights that can be studied in more detail.

Further studies should explore:

- The physiological and neurohormonal correlates of “toxic hunger” and of “true hunger“, including measures of oxidative stress and ghrelin levels (nicknamed the ‘hunger hormone’ because it stimulates appetite, increases food intake and promotes fat storage) in people who adhere to the high nutrient density diet and the previous usual diet.

- How long the typical “withdrawal phase” from the previous usual diet lasts as people shift to the high nutrient density diet.

This information would be valuable in clinical efforts to support those who are making the change to healthier eating patterns.

Study conclusions in brief

- Significant differences were found in the symptoms, location and unpleasantness of hunger on the high nutrient density diet compared to the participants’ previous usual diet in a large sample of people who had made the shift to a diet high in micronutrients and lower in calories.

- Hunger is one of the major impediments to successful weight loss.

- It is not simply the caloric content, but more importantly, the micronutrient density of a diet that influences the experience of hunger.

- There is an initial phase of adjustment after transitioning from the usual diet to the high nutrient density diet, during which a person experiences “toxic hunger” due to withdrawal from pro-inflammatory foods.

- A high nutrient density diet can result in a sustainable eating pattern that leads to weight loss and improved health.

- Further studies are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

- These findings may have important implications in the global effort to control rates of obesity and related chronic diseases.

Joe’s final comments

Homeostasis

This study confirms findings from my personal limited research. Namely, that the body craves homeostasis and has all the natural architecture and processes in place to achieve this if, and only if, two conditions are met:

- The toxic load on the body is reduced to as low a level as possible, and

- There is an optimal dietary intake of sufficient antioxidising, anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic micronutrients.

Given the foregoing, I believe that the body will heal itself and maintain optimal health if given appropriate nutrients.

Brain/body battle

However, if the body is bombarded with toxic “food”, then it will be continually struggling to reach homeostasis – resulting in symptoms such as those described in the study. Our brains learn to tell us one thing (that we are hungry) while our body is telling us another (that it’s full of toxins and needs to remove them). In the majority of cases nowadays, it appears that the brain wins this battle – as can be seen by the explosion in cases of obesity and diet-related diseases.

Hunger & the transition to a WFPB diet

I have noticed a change in hunger pangs since transitioning to a WFPB diet. Previously, I would experience cravings that simply had to be satisfied – cakes, ice-cream, takeaways, etc seemed like the only solution to a problem over which I had little conscious control. I now experience almost no hunger pangs like this. Eating has become something calm and therapeutic. This is echoed by what I hear reported by friends, family and clients who have similarly made the transition to a WFPB diet.

When we eat foods that are in harmony with our biochemistry, toxins, cancerous cells and fat deposits no longer build up and linger in the body. We feel healthy and the brain is not therefore sent on a wild goose (or chicken McNugget) chase in search of quick dopamine fixes to relieve the bodily discomfort caused by a low-nutrient/high-toxin diet.

Appendix

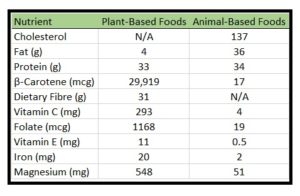

Low- / High-nutrient value foods

The following chart (see here for more details on ANDI scores) gives an idea of what foods are classified as being either high or low in nutrient value:

These are the sort of nutrients being evaluated within the above study:

ANDI measures calcium; the carotenoids – beta carotene, alpha carotene, lutein, zeaxanthin, and lycopene; fibre; folate; glucosinolates; iron; magnesium; niacin; selenium; vitamins B1 (thiamine), B2 (riboflavin), B6, B12, C, and E; and zinc, plus the ORAC (oxygen radical absorbance capacity) score X 2. Most importantly, the ANDI scores are based on calories, not volume or weight of food, so a lower-calorie food with more nutrients scores higher than a calorie-dense food, which is why foods like iceberg lettuce and kale score high.

References

- Chobotova K. Aging and Cancer: Converging Routes to Disease Prevention. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2009;8:115–122. [PubMed]

- Devaraj S, Wang-Polagruto J, Polagruto J, Keen CL, Jialal I, Devaraj S, Wang-Polagruto J, Polagruto J, Keen CL, Jialal I. High-fat, energy-dense, fast-food-style breakfast results in an increase in oxidative stress in metabolic syndrome. Metabolism: Clinical & Experimental. 2008;57:867–870.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Egger G, Dixon J. Inflammatory effects of nutritional stimuli: further support for the need for a big picture approach to tackling obesity and chronic disease. Obesity Reviews. pp. 137–149. [PubMed][Cross Ref]

- Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L. Major dietary patterns in relation to general obesity and central adiposity among Iranian women. Journal of Nutrition. 2008;138:358–363. [PubMed]

- Devaraj S, Mathur S, Basu A, Aung HH, Vasu VT, Meyers S, Jialal I, Devaraj S, Mathur S, Basu A. et al. A dose-response study on the effects of purified lycopene supplementation on biomarkers of oxidative stress. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2008;27:267–273. [PMC free article][PubMed]

- Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L, Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L. Dietary flavonoid intake and cardiovascular mortality. British Journal of Nutrition. 2008;100:695–697. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508945700. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Esmaillzadeh A, Kimiagar M, Mehrabi Y, Azadbakht L, Hu FB, Willett WC. Fruit and vegetable intakes, C-reactive protein, and the metabolic syndrome. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84:1489–1497. [PubMed]

- O’Keefe JH, Gheewala NM, O’Keefe JO, O’Keefe JH, Gheewala NM, O’Keefe JO. Dietary strategies for improving post-prandial glucose, lipids, inflammation, and cardiovascular health. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.016. [PubMed][Cross Ref]

- Bose KS, Agrawal BK, Bose KSC. Effect of lycopene from tomatoes (cooked) on plasma antioxidant enzymes, lipid peroxidation rate and lipid profile in grade-I hypertension. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism. 2007;51:477–481. [PubMed]

- Thompson HJ, Heimendinger J, Haegele A, Sedlacek SM, Gillette C, O’Neill C, Wolfe P, Conry C. Effect of increased vegetable and fruit consumption on markers of oxidative cellular damage. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:2261–2266. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.12.2261. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Bello NT, Hajnal A. Dopamine and binge eating behaviors. Pharmacology Biochemistry and behavior. 2010. in press Corrected Proof. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Berthoud HR. Neural control of appetite: cross-talk between homeostatic and non-homeostatic systems. Appetite. 2004;43:315–317. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.04.009. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- SurveyMonkey.com. Survey Monkey. Palo Alto, CA;

- Friedman MI, Ulrich P, Mattes RD. A Figurative Measure of Subjective Hunger Sensations. Appetite. 1999;32:395–404. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0230. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Karlsson J, Persson LO, Sjostrom L, Sullivan M. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2000;24:1715–1725. [PubMed]

- Lowe MR, Friedman MI, Mattes R, Kopyt D, Gayda C. Comparison of verbal and pictorial measures of hunger during fasting in normal weight and obese subjects. Obesity Research. 2000;8:566–574. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.73. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Gibbons JD. Nonparametric statistics: an introduction. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993.

- Sarter B, Campbell T, Fuhrman J. Effect of a high-nutrient density diet on long-term weight loss: a retrospective chart review. Alternative Therapies Health Med. 2008;14:48–51. [PubMed]

- Thompson HJ, Heimendinger J, Gillette C, Sedlacek SM, Haegele A, O’Neill C, Wolfe P, Thompson HJ, Heimendinger J, Gillette C. et al. In vivo investigation of changes in biomarkers of oxidative stress induced by plant food rich diets. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry. 2005;53:6126–6132. [PubMed]

- Peairs AT, Rankin JW, Peairs AT, Rankin JW. Inflammatory response to a high-fat, low-carbohydrate weight loss diet: effect of antioxidants. Obesity. 2008;16:1573–1578. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.252.[PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Patel C, Ghanim H, Ravishankar S, Sia CL, Viswanathan P, Mohanty P, Dandona P, Patel C, Ghanim H, Ravishankar S. et al. Prolonged reactive oxygen species generation and nuclear factor-kappaB activation after a high-fat, high-carbohydrate meal in the obese. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2007;92:4476–4479. [PubMed]

- Khansari N, Shakiba Y, Mahmoudi M. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age-related diseases and cancer. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2009;3:73–80. doi: 10.2174/187221309787158371. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Federico A, Morgillo F, Tuccillo C, Ciardiello F, Loguercio C, Federico A, Morgillo F, Tuccillo C, Ciardiello F, Loguercio C. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in human carcinogenesis. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;121:2381–2386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23192. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Willcox JK, Ash SL, Catignani GL, Willcox JK, Ash SL, Catignani GL. Antioxidants and prevention of chronic disease. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition. 2004;44:275–295. [PubMed]

- Guo W, Kong E, Meydani M, Guo W, Kong E, Meydani M. Dietary polyphenols, inflammation, and cancer. Nutrition & Cancer. 2009;61:807–810. [PubMed]

- Vives-Bauza C, Anand M, Shirazi AK, Magrane J, Gao J, Vollmer-Snarr HR, Manfredi G, Finnemann SC, Vives-Bauza C, Anand M. et al. The age lipid A2E and mitochondrial dysfunction synergistically impair phagocytosis by retinal pigment epithelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:24770–24780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800706200. [PMC free article] [PubMed][Cross Ref]

- Bockowski L, Sobaniec W, Kulak W, Smigielska-Kuzia J, Bockowski L, Sobaniec W, Kulak W, Smigielska-Kuzia J. Serum and intraerythrocyte antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxides in children with migraine. Pharmacological Reports: PR. 2008;60:542–548. [PubMed]

- Johnson PM, Kenny PJ, Johnson PM, Kenny PJ. Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13:635–641. doi: 10.1038/nn.2519. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Scanlan N. Compromised hepatic detoxification in companion animals and its correction via nutritional supplementation and modified fasting. Alternative Medicine Review. 2001;6(Suppl):S24–37. [PubMed]

- Blumenthal DM, Gold MS, Blumenthal DM, Gold MS. Neurobiology of food addiction. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 2010;13:359–365. [PubMed]

- Cohen DA, Cohen DA. Neurophysiological pathways to obesity: below awareness and beyond individual control. Diabetes. 2008;57:1768–1773. doi: 10.2337/db08-0163. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Corwin RL, Grigson PS, Corwin RL, Grigson PS. Symposium overview–Food addiction: fact or fiction? Journal of Nutrition. 2009;139:617–619. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.097691. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Dagher A. The neurobiology of appetite: hunger as addiction. International Journal of Obesity. 2009;33(Suppl 2):S30–33. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.69. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Davis C, Carter JC. Compulsive overeating as an addiction disorder. A review of theory and evidence. Appetite. 2009;53:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.018. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Del Parigi A, Chen K, Salbe AD, Reiman EM, Tataranni PA. Are We Addicted to Food? Obesity. 2003;11:493–495. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.68. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Gosnell BA, Levine AS. Reward systems and food intake: role of opioids. International Journal of Obesity. 2009;33(Suppl 2):S54–58. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.73. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Ifland JR, Preuss HG, Marcus MT, Rourke KM, Taylor WC, Burau K, Jacobs WS, Kadish W, Manso G. Refined food addiction: a classic substance use disorder. Medical Hypotheses. 2009;72:518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.11.035. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Johnson PM, Kenny PJ. Nat Neurosci. 2010; Dopamine D2 receptors in addiction-like reward dysfunction and compulsive eating in obese rats. advance online publication. [PMC free article][PubMed]

- Liu Y, von Deneen KM, Kobeissy FH, Gold MS, Liu Y, von Deneen KM, Kobeissy FH, Gold MS. Food addiction and obesity: evidence from bench to bedside. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. pp. 133–145. [PubMed]

- Pelchat ML, Pelchat ML. Food addiction in humans. Journal of Nutrition. 2009;139:620–622. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.097816. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Spring B, Schneider K, Smith M, Kendzor D, Appelhans B, Hedeker D, Pagoto S, Spring B, Schneider K, Smith M. et al. Abuse potential of carbohydrates for overweight carbohydrate cravers. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:637–647. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1085-z. [PMC free article][PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Yanover T, Sacco WP. Eating beyond satiety and body mass index. Eating & Weight Disorders: EWD. 2008;13:119–128. [PubMed]

- Yeomans MR, Yeomans MR. Alcohol, appetite and energy balance: is alcohol intake a risk factor for obesity? Physiology & behavior. pp. 82–89. [PubMed]

- Olusi SO. Obesity is an independent risk factor for plasma lipid peroxidation and depletion of erythrocyte cytoprotectic enzymes in humans. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2002;26:1159–1164.[PubMed]

- Arumugam V, Lee JS, Nowak JK, Pohle RJ, Nyrop JE, Leddy JJ, Pelkman CL, Arumugam V, Lee JS, Nowak JK. et al. A high-glycemic meal pattern elicited increased subjective appetite sensations in overweight and obese women. Appetite. 2008;50:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.07.003.[PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Fajcsak Z, Gabor A, Kovacs V, Martos E, Fajcsak Z, Gabor A, Kovacs V, Martos E. The effects of 6-week low glycemic load diet based on low glycemic index foods in overweight/obese children–pilot study. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2008;27:12–21. [PubMed]

- Flint A, Gregersen NT, Gluud LL, Moller BK, Raben A, Tetens I, Verdich C, Astrup A, Flint A, Gregersen NT. et al. Associations between postprandial insulin and blood glucose responses, appetite sensations and energy intake in normal weight and overweight individuals: a meta-analysis of test meal studies. British Journal of Nutrition. 2007;98:17–25. doi: 10.1017/S000711450768297X.[PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Harrington S, Harrington S. The role of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in adolescent obesity: a review of the literature. Journal of School Nursing. 2008;24:3–12. doi: 10.1177/10598405080240010201. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Bosch G, Verbrugghe A, Hesta M, Holst JJ, van der Poel AF, Janssens GP, Hendriks WH. The effects of dietary fibre type on satiety-related hormones and voluntary food intake in dogs. ritish Journal of Nutrition. 2009;102:318–325. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508149194. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Cotton JR, Burley VJ, Weststrate JA, Blundell JE, Cotton JR, Burley VJ, Weststrate JA, Blundell JE. Dietary fat and appetite: similarities and differences in the satiating effect of meals supplemented with either fat or carbohydrate. Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics. 2007;20:186–199.[PubMed]

- Duckworth LC, Gately PJ, Radley D, Cooke CB, King RF, Hill AJ, Duckworth LC, Gately PJ, Radley D, Cooke CB. et al. RCT of a high-protein diet on hunger motivation and weight-loss in obese children: an extension and replication. Obesity. 2009;17:1808–1810. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.95. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Flood-Obbagy JE, Rolls BJ, Flood-Obbagy JE, Rolls BJ. The effect of fruit in different forms on energy intake and satiety at a meal. Appetite. 2009;52:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.001.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Gilbert JA, Drapeau V, Astrup A, Tremblay A, Gilbert JA, Drapeau V, Astrup A, Tremblay A. Relationship between diet-induced changes in body fat and appetite sensations in women. Appetite. 2009;52:809–812. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.04.003. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Lemieux S, Lapointe A, Lemieux S, Lapointe A. Dietary approaches to manage body weight. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice & Research. 2008;69:3. p following 26. [PubMed]

- Lindqvist A, Baelemans A, Erlanson-Albertsson C, Lindqvist A, Baelemans A, Erlanson-Albertsson C. Effects of sucrose, glucose and fructose on peripheral and central appetite signals. Regulatory Peptides. 2008;150:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2008.06.008. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Lyly M, Liukkonen KH, Salmenkallio-Marttila M, Karhunen L, Poutanen K, Lahteenmaki L, Lyly M. Fibre in beverages can enhance perceived satiety. European Journal of Nutrition. 2009;48:251–258. doi: 10.1007/s00394-009-0009-y. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Monsivais P, Perrigue MM, Drewnowski A, Monsivais P, Perrigue MM, Drewnowski A. Sugars and satiety: does the type of sweetener make a difference? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007;86:116–123. [PubMed]

- Niwano Y, Adachi T, Kashimura J, Sakata T, Sasaki H, Sekine K, Yamamoto S, Yonekubo A, Kimura S, Niwano Y. et al. Is glycemic index of food a feasible predictor of appetite, hunger, and satiety? Journal of Nutritional Science & Vitaminology. 2009;55:201–207. [PubMed]

- Parra D, Ramel A, Bandarra N, Kiely M, Martinez JA, Thorsdottir I, Parra D, Ramel A, Bandarra N, Kiely M. et al. A diet rich in long chain omega-3 fatty acids modulates satiety in overweight and obese volunteers during weight loss. Appetite. 2008;51:676–680. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.06.003.[PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Rodriguez-Rodriguez E, Aparicio A, Bermejo LM, Lopez-Sobaler AM, Ortega RM. Changes in the sensation of hunger and well-being before and after meals in overweight/obese women following two types of hypoenergetic diet. Public Health Nutrition. 2009;12:44–50. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008001912. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, Smith SR, Ryan DH, Anton SD, McManus K, Champagne CM, Bishop LM, Laranjo N. et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:859–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804748. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Aston LM, Stokes CS, Jebb SA. No effect of a diet with a reduced glycaemic index on satiety, energy intake and body weight in overweight and obese women. International Journal of Obesity. 2008;32:160–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803717. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Major GC, Doucet E, Jacqmain M, St-Onge M, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Major GC, Doucet E, Jacqmain M, St-Onge M. et al. Multivitamin and dietary supplements, body weight and appetite: results from a cross-sectional and a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. British Journal of Nutrition. 2008;99:1157–1167. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507853335. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Ames BN. Micronutrients prevent cancer and delay aging. Toxicology Letters. 1998;102-103:5–18. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4274(98)00269-0. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Astley SB, Elliott RM, Archer DB, Southon S, Astley SB, Elliott RM, Archer DB, Southon S. Increased cellular carotenoid levels reduce the persistence of DNA single-strand breaks after oxidative challenge. Nutrition & Cancer. 2002;43:202–213. [PubMed]

- Aviram M, Kaplan M, Rosenblat M, Fuhrman B. Dietary antioxidants and paraoxonases against LDL oxidation and atherosclerosis development. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. 2005. pp. 263–300. full_text. [PubMed]

- Collins AR, Harrington V, Drew J, Melvin R, Collins AR, Harrington V, Drew J, Melvin R. Nutritional modulation of DNA repair in a human intervention study. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:511–515. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.3.511. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Ferguson LR, Philpott M, Karunasinghe N, Ferguson LR, Philpott M, Karunasinghe N. Dietary cancer and prevention using antimutagens. Toxicology. 2004;198:147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.01.035. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Joseph JA, Denisova NA, Bielinski D, Fisher DR, Shukitt-Hale B. Oxidative stress protection and vulnerability in aging: putative nutritional implications for intervention. Mechanisms of Ageing & Development. 2000;116:141–153. [PubMed]

- Martin KR, Failla ML, Smith JC Jr. Beta-carotene and lutein protect HepG2 human liver cells against oxidant-induced damage. Journal of Nutrition. 1996;126:2098–2106. [PubMed]

- O’Brien NM, Carpenter R, O’Callaghan YC, O’Grady MN, Kerry JP, O’Brien NM, Carpenter R, O’Callaghan YC, O’Grady MN, Kerry JP. Modulatory effects of resveratrol, citroflavan-3-ol, and plant-derived extracts on oxidative stress in U937 cells. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2006;9:187–195. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2006.9.187. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- O’Brien NM, Woods JA, Aherne SA, O’Callaghan YC. Cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and oxidative reactions in cell-culture models: modulatory effects of phytochemicals. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2000;28:22–26. [PubMed]

- Prior RL, Prior RL. Fruits and vegetables in the prevention of cellular oxidative damage. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;78:570S–578S. [PubMed]

- Schaefer S, Baum M, Eisenbrand G, Janzowski C, Schaefer S, Baum M, Eisenbrand G, Janzowski C. Modulation of oxidative cell damage by reconstituted mixtures of phenolic apple juice extracts in human colon cell lines. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2006;50:413–417. [PubMed]

- Singh M, Arseneault M, Sanderson T, Murthy V, Ramassamy C, Singh M, Arseneault M, Sanderson T, Murthy V, Ramassamy C. Challenges for research on polyphenols from foods in Alzheimer’s disease: bioavailability, metabolism, and cellular and molecular mechanisms. Journal of Agricultural & Food Chemistry. 2008;56:4855–4873. [PubMed]

- Sudheer AR, Muthukumaran S, Devipriya N, Menon VP, Sudheer AR, Muthukumaran S, Devipriya N, Menon VP. Ellagic acid, a natural polyphenol protects rat peripheral blood lymphocytes against nicotine-induced cellular and DNA damage in vitro: with the comparison of N-acetylcysteine. Toxicology. 2007;230:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.10.010. [PubMed] [Cross Ref]

- Tarozzi A, Hrelia S, Angeloni C, Morroni F, Biagi P, Guardigli M, Cantelli-Forti G, Hrelia P. Antioxidant effectiveness of organically and non-organically grown red oranges in cell culture systems. European Journal of Nutrition. 2006;45:152–158. doi: 10.1007/s00394-005-0575-6.[PubMed] [Cross Ref]

-

A rice cooker and slow cooker are useful additions, but the one that I tend to use almost daily is a pressure cooker. Drs Joel Fuhrman and Michael Greger make it clear that eating beans every day is one of the healthiest things you can do – particularly when bean-eating is linked to healthy longevity in several epidemiological studies

A rice cooker and slow cooker are useful additions, but the one that I tend to use almost daily is a pressure cooker. Drs Joel Fuhrman and Michael Greger make it clear that eating beans every day is one of the healthiest things you can do – particularly when bean-eating is linked to healthy longevity in several epidemiological studies  Another piece of kit that I use almost every day is a small coffee/spice grinder. I include a tablespoon of ground flaxseeds and chia seeds in my daily diet (along with 6 halves of walnuts) so that I get enough ALA to make the EPA/DHA long-chain omega-3 fatty acids

Another piece of kit that I use almost every day is a small coffee/spice grinder. I include a tablespoon of ground flaxseeds and chia seeds in my daily diet (along with 6 halves of walnuts) so that I get enough ALA to make the EPA/DHA long-chain omega-3 fatty acids  This is the same when it comes to kitchen tools. It’s always best to spend a bit extra on a really good quality sharp chef’s knife. Not only does it make such a difference in food prep, but it makes it more enjoyable and safer.

This is the same when it comes to kitchen tools. It’s always best to spend a bit extra on a really good quality sharp chef’s knife. Not only does it make such a difference in food prep, but it makes it more enjoyable and safer.

Joel Fuhrman, M.D. is a board-certified family physician, six-time New York Times best-selling author and internationally recognised expert on nutrition and natural healing.

Joel Fuhrman, M.D. is a board-certified family physician, six-time New York Times best-selling author and internationally recognised expert on nutrition and natural healing.