You may never have heard of these two terms, “wholism” and “reductionism”, but the war between them is not just a war of words, it’s a war of paradigms. One of these paradigms is unfortunately winning most of the battles, and the result is an escalating public health crisis.

First, let’s look at what I mean by “paradigm”. A good example is the difference between geocentric and heliocentric world views that came to a head around the 15th-16th centuries. Before the so-called Copernican Revolution (involving intellectual giants such as Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543), Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) and Galileo Galilei (1564-1642), the accepted and, for the most part, unchallenged paradigm was that the Sun and other planets revolved around the Earth, and the stars were all fixed in the heavens, just like it said in the Bible. Post-Revoltion, there was a slow but ultimately complete “paradigm shift” which meant that everyone now accepts that the Earth and other planets revolve around the Sun, and the stars are no longer just pin-pricks in some form of heavenly firmament.

Put simply, in terms of nutrition, wholism (a term adopted by Professor T Colin Campbell from the similar and better-known term “holism”) deals with whole diet and its effects on the whole person; whereas reductionism looks at specific elements of diet and their effect on specific parts of the person (like a specific gene for loving or hating Marmite).

The seemingly unstoppable increase in diet-related chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and obesity, is simply not being addressed by the ever more precise research being undertaken by scientists, whether they are chemists looking at a specific chemical that can target particular cellular behaviour or a geneticist looking at which gene is responsible for the onset of a particular disease.

Of course it’s necessary to narrow one’s visual field to a specific area of investigation when it is appropriate (for instance, using a microscope to distinguish which virus has infected a given tissue sample); but there is a general tendency nowadays within nutritional science to exclusively apply the microscope (metaphorically speaking) to every public health issue.

Let’s look at an example: A recent report revealed that half of our schoolchildren are now dangerously overweight or obese.

A reductionist response could be to look for and try and isolate the gene that causes obesity in children. £millions or even £billions could be poured into expensive genetic research to find this “needle in the haystack”. Whereas a wholistic response could be to look at what societal changes have occurred that might account for this unwelcome change in the health of schoolchildren. You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to see that there has been a significant change in the average diets that schoolchildren are now eating when compared to previous generations.

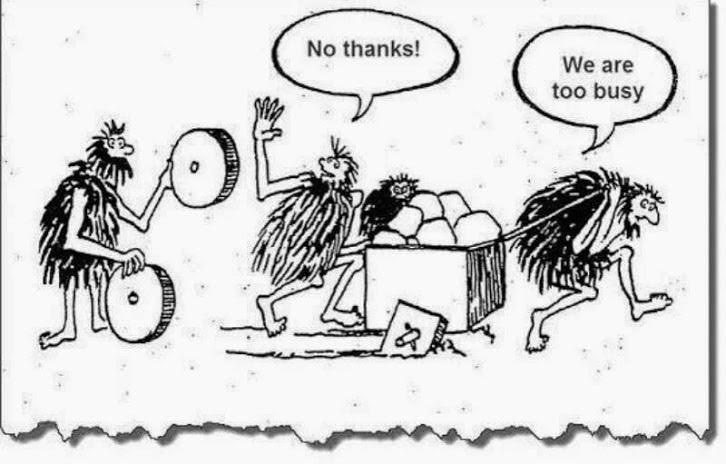

With the reductionist response, one could expect that years and even decades could pass without anything being discovered, and all the while more and more children are likely to become obese.

With the wholistic approach, a solution could theoretically be found very quickly – legislate to improve school meals, increase junk food taxes, ban advertising of unhealthy foods to children, and so forth. The chances are that obesity statistics would start to improve the more practical efforts were made to change laws, educate parents and improve children’s diets. And whilst it might appear that governments do make some moves in this direction, their efforts to implement substantial solutions end up being quasi-wholistic because they are generally hamstrung by the pressure imposed on them by Big Pharma, Big Medicine and Big Agriculture – and the majority of research funding, whether directly or indirectly (e.g. through universities and other institutions), greatly influences which research is most powerfully supported in government circles and reflected in the media to the public.

But even if simple dietary changes could significantly reduce childhood obesity, it would probably not make the reductionists happy. They would still want to delve down into minutiae and find a biological mechanism that could then be controlled somehow, most likely by a drug that could be patented and sold for profit. There is no profit to be made from people simply changing their diets. And there is certainly no profit to be made by pharmaceutical companies or medical organisations from a population full of healthy people.

But let’s say that the geneticists do find a gene that is strongly associated with childhood obesity. It may still take years or decades of research to transfer that information into a fully-tested and certified treatment, probably in the form of a drug. And even if the obesity pill works in the trials they’ve undertaken, there is no guarantee that it will work within the general population, or that it will be free of serious side-effects only apparent years or decades later (remember Thalidomide?), or if it is too expensive for the majority of people to afford or indeed if the percentage improvement attributable to the drug would bear any comparison with the size of improvement made simply by changing dietary intake.

There is nothing wrong with geneticists exploring the fascinating world of genes, nor is there anything wrong with scientists trying to find what makes one person’s personality different from another’s, or any of the other intriguing questions that beg to be researched and answered by the curious and searching human mind.

What IS a problem, though, is when the ONLY approach to solving scientific problems, particularly those directly linked to public health, is an approach which ignores anything that is “fuzzy” and too…well, human! The funding for most of the scientific research that is undertaken nowadays is only available if there is a tangible and clear hope of achieving a binary, black and white result:

- 1. A always precedes B.

- 2. B always follows A.

- 3. There is no C that could also cause B.

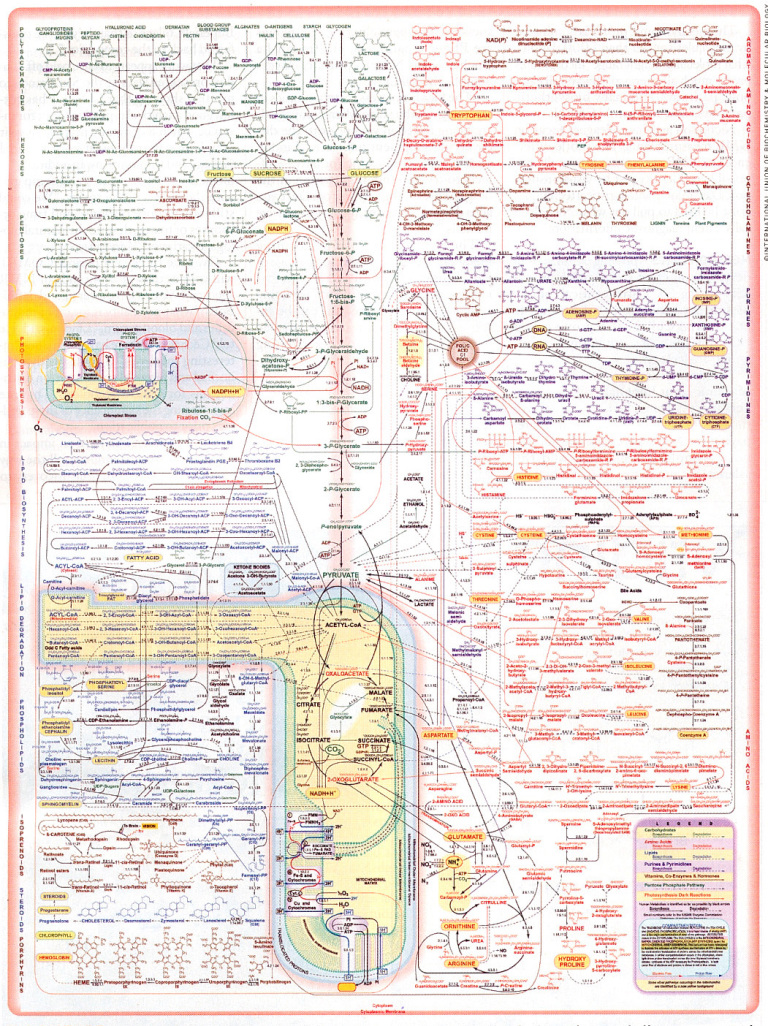

Human behaviour and particularly human nutrition on a population-wide level can never conform to this linear causal pattern. Indeed, even one single cell does not and arguably never can be analysed or understood fully by any amount of analysis – just as can be seen in quantum physics (where electrons can exist in two places at the same time – or cease to exist and reappear elsewhere in ways that can never conform to what we think of as causality), the more we delve into our biochemistry, the more we appreciate how much there is that we can never fully know. Just look at the following diagrammatic representation of just the partial metabolic processes involved in one single cell:

Professor T Colin Campbell explains (1.) the dilemma like this:

“The fact that each nutrient passes through such a maze of reaction pathways suggests that each nutrient also is likely to participate in multiple health and disease outcomes. The one nutrient/one disease relationship implied by reductionism, although widely popular, is simply incorrect. Every nutrient-like chemical that enters this complex system of reactions creates a rippling effect that may extend far into the pool of metabolism. And with every bite of food we eat, there are tens and probably hundreds of thousands of food chemicals entering this metabolism pool more or less simultaneously.”

Whilst it is understandable that the human mind is inquisitive and naturally wants to simplify complexity, is it really essential to map the inter-, intra- and extra-cellular labyrinthine world of the 100 trillion cells comprising the human body before we can identify and apply timely solutions to public health issues?

In any event, our cellular make-up is only one aspect of what constitutes the indefinably complex entity that is a human being. Can we truly ever expect to see a cellular or genetic “cog” that explains what it is to be a friend, a lover, a parent? Why we find beauty in a sunset?

Tackling childhood obesity head-on in the messy “real” world of human populations represents the sort of indeterminate complexity that does not attract large government or institutional funding. More effort goes into producing incomprehensibly complex charts such as the one above than goes into practical measures to help children live full and productive lives. This is not to say that scientists, governments and organisations do not care about the lives of real people – particularly real schoolchildren. Rather, my contention is that they are so wrapped up in doing things the way that things have been done for so long (“stuck inside the paradigm”) that they may, in part, genuinely believe that their way is the ONLY way to solve such public health crises.

This is why I believe it is appropriate to apply the term “paradigm” to the general outlook and approach that science and medicine has been immersed in for at least the past 50 years – probably since the joint effects of two discoveries: the so-called completed list of vitamins and the structure of DNA. It is also the reason why incredibly convincing population studies, such as The China Study, come under attack from reductionist thinkers. They attack such wide-scale population studies because there is no single causal link demonstrated. This is even the case when the study identifies significant differences in health markers (e.g. cancer, heart disease and type 2 diabetes) between those Chinese populations eating the traditional plant-based diets and those Chinese populations that have adopted the Standard American Diet (SAD).

There is good reason for this lack of indisputable causality: and the reason is that it is simply impossible to prove a single causal link between health and diet when, as Professor Campbell indicated above, no single nutritional input ever causes just one single biochemical response. But such linear responses are just what scientists have habitually expected to discover when the overriding world-view they have been exposed to all their academic and professional lives aims to reduce all complexity down to minute and simple mechanics.

You will have heard the saying “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts”. Intuitively obvious, but possibly not so in the majority of research laboratories around the world.

The assumption that it should be possible to find such a causal link is based on a mechanistic reductionist ideal of the Universe. The likes of Ray Kurtzweil et al consider that one day we will be able to understand everything about ourselves – biology, emotions, personality – by drilling down deeper and deeper, smaller and smaller into the world of micro and nano particles until we find all the little “cogs” and see how they are all connected. We will then be able to predict all events in the “macro world” and reproduce them in better ways with far more durable materials than human flesh and blood.

Of course we don’t want to return to an age of religion and mysticism, where all events were caused by unknown and unknowable forces, spirits and demons. Where everything in biology and personality could be accounted for by the four humours – blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm! We all enjoy huge benefits from the application of reductionist approaches to finding causes and cures for TB and smallpox, and without this approach doctors might still be delivering babies with unwashed hands after having chopped up cadavers or been to the toilet, or both.

Also, I can see how a reductionist approach can be very attractive. It’s neat and orderly and avoids that great enemy of the reductionist thinker, namely, uncertainty.

But I propose that the answer to childhood obesity is both complex and simple.

It’s simple because all it requires is that we feed our children the natural diet for our species (ideally consisting completely or in the main part of whole plant foods), while ensuring that they get some regular exercise.

It’s complex because WE – our biochemistry, our personalities, our societies – ARE complex.

But effective and timely solutions to childhood obesity and many other public health crises are much more likely to be found with the help of two eyes rather than the help of a two million pound electron microscope.

Ample evidence already points to dietary change being the major factor needed in order to solve this escalating health problem. So much evidence, indeed, that I have not even bothered to list it in this article. Just scan through the databases of the NCBI or NIHR to see that sufficient research already links obesity to diet. But in spite of this, the main thrust of government and medical policy derives from what is called “Gold Standard” research, where the majority of research funding (and resultant credibility) is assigned to randomised controlled trials (RCT’s) that control all potential extraneous biases. And, clearly, you cannot do with when dealing with the nutritional and behavioural diversity that exists in the wider world of society as a whole.

This situation can be further explained by the analogy of an elephant in a room along with 60,000 blind scientists who are each responsible for describing one individual facet in minute detail. They can talk at length about the life-cycle of one of the thousands of species of bacteria colonising a crack between two toes, or churn out publications on the chemical components of a particular pigment within a hair from its tail. Yes, it’s true that they become incredibly expert in their own field of research, but it takes just one non-visually impaired child running into the room to be able to announce that there’s a bleedin’ great elephant standing there!

And to the surprise of the child, these 60,000 blind researchers with one voice ask “what’s an elephant?”

To those who have their eyes open to the whole picture, they can see that our example of childhood obesity is but one of the many chronic health conditions clearly caused by diet, and it’s always the same diet, the one that contains far too much animal protein, saturated fats, salt, sugar and processed junk, and far too little whole plant foods.

Diet is a “zero-sum” affair. Whenever one unhealthy food item goes into your mouth it means that another more healthy food item didn’t. And it is the cumulative effect of this, meal after meal, day after day, year after year that leads inexorably to the near-epidemic diet-related health issues that are starting to bring our hospitals to a standstill.

A fish is hooked, thrown onto land, flops around for a bit in the air and then escapes back into the water. Eager to tell his fishy buddies about his experience, he starts talking to them about his time out of the water. “What’s water?” they all ask, looking at him as though he’s out of his scaly mind. When water is all that you know, there is no word for it…

You may enjoy another view of this issue by Dr. Michael Greger…

Bibliography

- Campbell, T. Colin. Whole: Rethinking the Science of Nutrition (p. 97). BenBella Books, Inc.. Kindle Edition.