A study nicknamed the Office Candy Dish looked at how our eating choices are affected by how visible and easily available particular foods are. Most of us have a candy dish lurking somewhere – where’s yours?

Dr Brian Wansink’s Study

Questions to answer:

- how does the visibility and proximity (closeness) of a food influence consumption volume?

- are proximate foods consumed more frequently because they are proximate, or are they consumed more frequently because people lose track of how much they eat?

Research methods and procedures:

- 4-week study involving chocolate candy consumption of 40 adult secretaries

- proximity – chocolates placed either on the participant’s desk or 2 m from the desk

- visibility – chocolates placed in covered bowls that were either clear or opaque

- chocolates replenished each evening

- placement conditions rotated once a week

- daily consumption noted and follow-up questionnaires distributed and analysed

So what results do you think were found?

– More visibility led to more or less candy consumption?

– Closer proximity led to more or less candy consumption?

Results

– more candies were eaten each day when they were more visible

– more candies were eaten when they were on the desk rather than 2 m away

– there was a tendency to underestimate daily consumption of candies when on desk

– conversely, there was a tendency to overestimate daily consumption of candies when placed 2 m away

These limited results bring us no great surprises, but they do reinforce the intuitively obvious notions that proximity and visibility of a food can consistently increase a person’s consumption of it. In addition, these results suggest that people may be biased to overestimate the consumption of foods that are further away, and to underestimate those that are closer.

But so what?

Understanding the psychology in this small study can help to throw light on how best we can manage our WFPBD. It is clear as soon as you walk out of your front door that we exist in a nutritionally toxic environment, with a Pizza Hut, McDonald’s or kebab shop on every corner, and almost every supermarket aisle chocked full of sugary, fatty, largely animal-based processed junk – tempting as they may be to the taste sensors that evolution has given us.

Ensuring that we have a favourable nutritional environment in our own homes seems to make good sense.

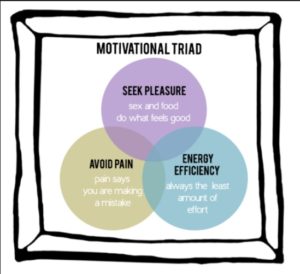

The Motivational Triad & The Pleasure Trap

Doug Lisle PhD explains that the Motivational Triad consists of three basic humans motivations:

- avoid pain

- seek pleasure

- conserve energy

It is, therefore, not difficult to understand that we are simply acting in accordance with our evolved nature when we find it difficult to ignore the tub of ice cream looking at us with its sad eyes every time we go into the freezer to take out the bag of frozen berries; or to avoid hearing the enticing song of the cookie jar that’s loitering on the kitchen shelf next to the organic steel-cut jumbo oats. Dr Lisle calls this dilemma The Pleasure Trap.

It is, therefore, not difficult to understand that we are simply acting in accordance with our evolved nature when we find it difficult to ignore the tub of ice cream looking at us with its sad eyes every time we go into the freezer to take out the bag of frozen berries; or to avoid hearing the enticing song of the cookie jar that’s loitering on the kitchen shelf next to the organic steel-cut jumbo oats. Dr Lisle calls this dilemma The Pleasure Trap.

Our bodies know full well that they can get a bigger hit of calories much more quickly from ice cream and cookies than from a bowl of berries and oats.

What wrong with a bit of self-discipline?

Of course, we can use self-discipline and will-power; but relying on these has never and will never be the best strategy for a successful and enjoyable lifetime of optimal nutrition. Sitting there and struggling with willpower every day for the next 5, 10, 20 or 50 years is not a winning proposition.

What is likely to be more successful and certainly a more pleasurable strategy is to get into mindless habits of achieving and maintaining your nutritional goals. This will then mean that you are letting the motivational triad work for you rather than against you:

What is likely to be more successful and certainly a more pleasurable strategy is to get into mindless habits of achieving and maintaining your nutritional goals. This will then mean that you are letting the motivational triad work for you rather than against you:

- avoiding any painful sense of loss at not letting yourself indulge in foods you would rather not eat

- enjoying the pleasure of just focusing on the foods you do want to eat

- and conserving energy by making it easy on yourself to only do what is in line with your personal dietary goals

So here are a few (pretty obvious) tips

[su_frame] Cookie Convenience #1 – The bad choice should always take a lot more effort. If you need to have a candy jar in the house, store it far away and out of sight – better still, remove it from the house completely.

Fridge Convenience #2 – Keep at least five healthy food options at the front part of the shelf in the fridge, especially at children’s height if you have kids and want them to eat healthily. Make it easy for you and your family to make good choices.

Recipe Convenience #3 – Make sure you have loads of wonderful recipes available, masses of attractively-stored healthy ingredients – frozen, in jars, fresh – and keep readily available all those kitchen gadgets you require to produce really tasty meals as quickly and easily as possible.

Green is Normal – Make it a normal thing to always have green leafy vegetables as a part of every single dinner. So the only choice is which greens to have.

Fruity & Attractive – Don’t stick sad-looking fruit in a dusty Tupperware bowl. Place fresh and varied-coloured fruit in a beautiful and easily reachable glass bowl.

Dishy & Attractive – When you serve up your food, make sure the serving dishes, crockery and cutlery are a pleasure to look at and use, and that the food looks appetising and colourful. Make every meal a special mindful occasion.

Safe Snacking – Keep healthy snacks easily available – fresh or (unsugared) dried fruits, nuts and seeds instead of a biscuit barrel or a tray of candies.

[/su_frame]

More on Dr Lisle’s Pleasure Trap and the Motivational Triad:

[qsm quiz=5]

References

Wansink B, Painter JE, Lee YK. The office candy dish: Proximity’s influence on estimated and actual consumption. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006 May; 30(5): 871-875.

Wansink B. Convenient, attractive, and normative: The CAN approach to making children slim by design. Child Obes. 2013 Aug; 9(4): 277-8.

Painter JE, Wansink B, Hieggelke JB. How visibility, convenience influence candy consumption. Appetite 2002; 38: 237–238.

Chandon P, Wansink B. Does stockpiling accelerate consumption. A convenience-salience framework of consumption stockpiling. J Marketing Res 2002; 39: 321–335.

Wansink B. Environmental factors that increase the food intake and consumption volume of unknowing consumers. Ann Rev Nutr 2004; 24: 455–479.

Wansink B, Sudman S. Consumer Panels, 2nd edn. American Marketing Association: Chicago, 2002.

Wansink B, Cheney MM. Super bowls: serving bowl size and food consumption. JAMA 2005; 293: 1727–1728.

Norcross JC, Mrykalo MS, Blagys MD. Auld lang syne: Success predictors, change processes, and self-reported outcomes of New Year’s resolvers and nonresolvers. J Clin Psychol. 2002; 58: 397-405.

Thomas PR. Improving America’s Diet and Health: From Recommendations to Action. National Academy Press: Washington, DC, 1991.

Glanz K, Basil M, Maibach E, Goldberg J, Snyder D. Why Americans eat what they do: taste, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. J Am Diet Assoc 1998; 98: 1118–1126.

Sporny LA, Contento IR. Stages of change in dietary fat reduction social psychological correlates. J Nutr Educ 1995; 27: 191–199.

Gould SJ. An interpretive study of purposeful, mood self regulating consumption: the consumption and mood framework. Psychol Marketing 1997; 14: 395–426.

Patel KA, Schlundt DG. Impact of moods and social context on eating behavior. Appetite 2001; 36: 111–118.

Oliver G, Wardle J, Gibson L. Stress, food choice: a laboratory study. Psychosomatic Med 2000; 62: 853–865.

Berry SL, Beatty WW, Klesges RC. Sensory, social influences on ice cream consumption by males, females in a laboratory setting. Appetite 1985; 6: 41–45.

Birch LL, Fisher JO. Mother’s child-feeding practices influence daughters’ eating, weight. Am J Clin Nutr 2000; 71: 1054–1061.

Terry K, Beck S. Eating style, food storage habits in the home: Assessment of obese, non-obese families. Behav Modification 1985; 9: 242–261.

Bauer PJ, Wewerk SS. One- to two-year-old’s recall of events: the more expressed, the more impressed. J Exp Child Psychol 1995; 59: 475–496.

Hearn MD, Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Doyle C, Smith M, Lin LS, et al. Environmental influences on dietary behavior among children: availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables. J Health Educ 1998; 29: 26–32.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Personality Social Psychol 1986; 51: 1173–1182.

Collier G, Hirsch E, Hamlin PH. Ecological determinants of reinforcement in rats. Physiol Behav 1972; 9: 705–716.

Levitsky DA. Putting behavior back into feeding behavior: a tribute to George Collier. Appetite 2002; 38: 143–148.

Doug Lisle PhD. Article: Breaking Free of the Dietary Pleasure Trap (https://nutritionstudies.org/breaking-free-dietary-pleasure-trap/)

Lee AY, Sternthal B. The effects of positive mood on memory. J Consumer Res 1999; 26: 115–127.