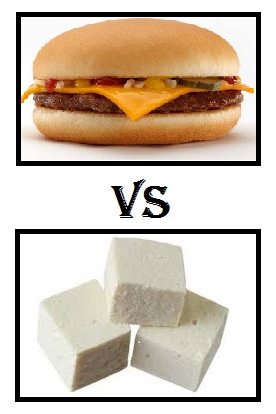

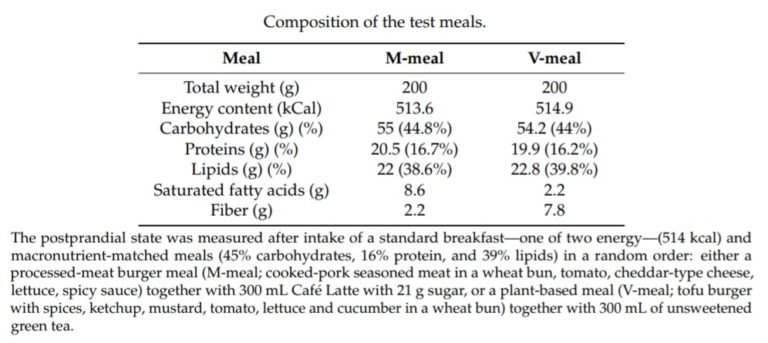

A January 2019 study 1 wanted to analyse how a specific number of postprandial (after eating) physiological indicators were affected in three different population groups by tucking in to either a typical processed-meat cheeseburger meal (CB) or a tofu burger meal (TB).

Study method

The three population groups were 20 each of:

- men with type 2 diabetes (T2D)

- obese men (OM)

- healthy men (HM)

The two meals were matched in terms of energy and macronutrients:

The health indicators being tested were gastrointestinal hormones involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism and satiety (the feeling of feeling ‘full’ from eating food).

Glucose metabolism (how the body was responding to the meal) was assessed at 0, 30, 60, 120 and 180 minutes after the meal via an analysis of each participant’s blood plasma, to check levels of the following hormones:

- glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) 2

- amylin 3 , and

- peptide YY (PYY) 4

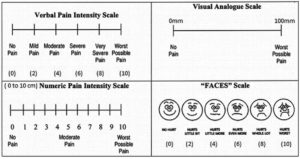

- satiety (the feeling of fullness itself) was assessed through what’s called a ‘visual analogue scale‘ 5

Study findings

After eating the tofu burger meal (when compared with the cheeseburger meal):

- GLP-1 increased in T2D and HM

- amylin increased in all groups

- PYY increased only in HM

- satiety increased in all groups

So what?

Well, this shows there’s a greater increase in glucose metabolising gut hormones and satiety following the consumption of a single plant-based meal with tofu when compared with an energy- and macronutrient-matched processed-meat meat and cheese meal. And what’s more, this happens in all three groups: diabetic, obese and healthy men.

By feeling more satiated, people eat less. By eating less, they avoid piling on extra weight as a result of foods (particularly processed, fatty, animal-based, salty, and sweet foods) ‘fooling’ the body into thinking it needs to consume more. The body treats plant-foods differently from processed and animal foods, releasing different hormones from the gut and affecting the brain differently (partly through satiety signalling).

Study discussion

The following points were raised within this study:

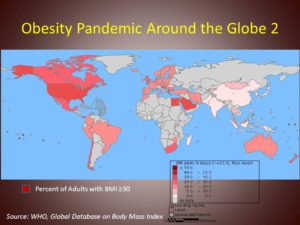

- obesity substantially increases the risk of:

- type 2 diabetes

- cardiovascular disease, and

- certain types of cancer 6

- improving dietary choices represents a primary prevention tool 7 8

- the influence of diet in the development of insulin resistance, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes is well-established 9 10 11

- gastrointestinal hormones are known to be involved in the regulation of glucose metabolism, energy homeostasis, satiety, and weight management 12

- ingestion of food triggers secretion of the incretin hormone GLP-1 from the gastrointestinal tract, which enhances insulin secretion and helps maintain glucose homeostasis 13

- the satiety hormones GLP-1 [9], peptide YY (PYY) [10], pancreatic polypeptide (PP) [11] and amylin [12] regulate appetite and energy homeostasis

- the release of the satiety hormones GLP-1, PYY and amylin can depend on meal composition and differs between impaired and normal glycaemic status 14

- consumption of red meat is associated (and the consumption of processed meat is very strongly associated) with risk of type 2 diabetes 15 16

- consuming any processed meats increases (by 33%) the risk of developing diabetes 17

- saturated fatty acids from meat and other animal products impairs insulin resistance and glucose tolerance 18 9 , and increases the risk of cardiovascular disease 19

- following plant-based diets (vegetarian) reduces risk of diabetes by 50% 20

- insulin sensitivity and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetics improves on a plant-based diet 21 22

Study conclusion

“Our findings indicate that plant-based meals with tofu may be an effective tool to increase postprandial secretion of gastrointestinal hormones, as well as promote satiety, compared to processed meat and cheese, in healthy, obese, and diabetic men. These positive properties may have practical implications for the prevention of type 2 diabetes.”

Final thoughts

The interesting subject of satiety has been covered previously, when we looked at the three mechanisms of satiety 23 .

The study covered in this blog is, of course, just of the many research projects which look at how plant-food compares with animal-food. If you’ve read some of the previous blogs on diabetes 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 and obesity 32 33 , you’ll already know that there’s a mountain of evidence that plant-based meals not only prevent, but also reverse these and many other non-communicable diseases.

The take-home message?

Ditch McDonald’s and get stuck into plant-based foods if, that is, you want optimal health and longevity. Your choice…

…if, that is, you’re lucky enough to be in a family or live in a society where there is any real choice.

References

- Nutrients. 2019 Jan 12;11(1). A Plant-Based Meal Increases Gastrointestinal Hormones and Satiety More Than an Energy- and Macronutrient-Matched Processed-Meat Meal in T2D, Obese, and Healthy Men: A Three-Group Randomized Crossover Study. Klementova M, Thieme L, Haluzik M, Pavlovicova R, Hill M, Pelikanova T, Kahleova H [↩]

- Glucagon-like peptide-1 is a 30 amino acid long peptide hormone. GLP-1 is an incretin; thus, it has the ability to decrease blood sugar levels in a glucose-dependent manner by enhancing the secretion of insulin. Peripherally, GLP-1 is known to affect gut motility, inhibit gastric acid secretion, and inhibit glucagon secretion. In the central nervous system, GLP-1 induces satiety, leading to reduced weight gain. In the pancreas, GLP-1 is now known to induce expansion of insulin-secreting β-cell mass, in addition to its most well-characterised effect: the augmentation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. [↩]

- Amylin is a peptide hormone secreted along with insulin from the pancreatic β-cells. It plays a role in glycaemic regulation by slowing gastric emptying and promoting satiety, thereby preventing postprandial spikes in blood glucose levels. peptide hormone that slows digestion. When carbohydrates stay in the stomach longer, they are converted to glucose and enter the bloodstream in a slower, more gradual manner. It helps to block glucagon secretion. Glucagon is a pancreatic hormone that raises the blood glucose level by stimulating the liver to release stored glucose. Without amylin, most people with diabetes produce extra glucagon when they eat; this can contribute to after-meal blood glucose spikes. By enhancing satiety, amylin helps to limit appetite and thus reduce the amount of food eaten during (and between) meals. [↩]

- Peptide YY s a hormone secreted from endocrine cells called L-cells in the small intestine. It’s secreted alongside the hormone glucagon-like peptide 1. It’s released after eating, circulates in the blood and works by binding to receptors in the brain. Binding of peptide YY to brain receptors decreases appetite and makes people feel full after eating. It also acts in the stomach and intestine to slow down the movement of food through the digestive tract. [↩]

- The visual analogue scale or visual analogue scale is a psychometric response scale which can be used in questionnaires. It is a measurement instrument for subjective characteristics or attitudes that cannot be directly measured. The following is a typical example:

[↩]

[↩] - GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [↩]

- Evert, A.B.; Boucher, J.L.; Cypress, M.; Dunbar, S.A.; Franz, M.J.; Mayer-Davis, E.J.; Neumiller, J.J.; Nwankwo, R.; Verdi, C.L.; Urbanski, P.; et al. Nutrition therapy recommendations for the management of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014, 37 (Suppl. 1), S120–S143. [↩]

- American Heart Association Nutrition Committee; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Appel, L.J.; Brands, M.; Carnethon, M.; Daniels, S.; Franch, H.A.; Franklin, B.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Harris, W.S.; et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation 2006, 114, 82–96. [↩]

- Feskens, E.J.; Virtanen, S.M.; Räsänen, L.; Tuomilehto, J.; Stengård, J.; Pekkanen, J.; Nissinen, A.; Kromhout, D. Dietary factors determining diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance. A 20-year follow-up of the Finnish and Dutch cohorts of the Seven Countries Study. Diabetes Care 1995, 18, 1104–1112. [↩] [↩]

- Fizelova, M.; Jauhiainen, R.; Stanˇcáková, A.; Kuusisto, J.; Laakso, M. Finnish Diabetes Risk Score Is Associated with Impaired Insulin Secretion and Insulin Sensitivity, Drug-Treated Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease: A Follow-Up Study of the METSIM Cohort. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166584. [↩]

- Mann, J.I.; De Leeuw, I.; Hermansen, K.; Karamanos, B.; Karlström, B.; Katsilambros, N.; Riccardi, G.; Rivellese, A.A.; Rizkalla, S.; Slama, G.; et al. Evidence-based nutritional approaches to the treatment and prevention of diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2004, 14, 373–394. [↩]

- Perry, B.; Wang, Y. Appetite regulation and weight control: The role of gut hormones. Nutr. Diabetes 2012, 2, e26. [↩]

- Meier, J.J. The contribution of incretin hormones to the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 23, 433–441. [↩]

- Belinova, L.; Kahleova, H.; Malinska, H.; Topolcan, O.; Vrzalova, J.; Oliyarnyk, O.; Kazdova, L.; Hill, M.; Pelikanova, T. Differential acute postprandial effects of processed meat and isocaloric vegan meals on the gastrointestinal hormone response in subjects suffering from type 2 diabetes and healthy controls: A randomized crossover study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107561. [↩]

- Aune, D.; Ursin, G.; Veierød, M.B. Meat consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2277–2287. [↩]

- Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Bernstein, A.M.; Schulze, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Red meat consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: 3 cohorts of US adults and an updated meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1088–1096. [↩]

- Vang, A.; Singh, P.N.; Lee, J.W.; Haddad, E.H.; Brinegar, C.H. Meats, processed meats, obesity, weight gain and occurrence of diabetes among adults: Findings from Adventist Health Studies. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 52, 96–104. [↩]

- Maron, D.J.; Fair, J.M.; Haskell, W.L. Saturated fat intake and insulin resistance in men with coronary artery disease. The Stanford Coronary Risk Intervention Project Investigators and Staff. Circulation 1991, 84, 2020–2027. [↩]

- Zong, G.; Li, Y.; Wanders, A.J.; Alssema, M.; Zock, P.L.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B.; Sun, Q. Intake of individual saturated fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women: Two prospective longitudinal cohort studies. BMJ 2016, 355, i5796. [↩]

- Tonstad, S.; Butler, T.; Yan, R.; Fraser, G.E. Type of Vegetarian Diet, Body Weight, and Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 791–796. [↩]

- Kahleova, H.; Matoulek, M.; Malinska, H.; Oliyarnik, O.; Kazdova, L.; Neskudla, T.; Skoch, A.; Hajek, M.; Hill, M.; Kahle, M.; et al. Vegetarian diet improves insulin resistance and oxidative stress markers more than conventional diet in subjects with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2011, 28, 549–559. [↩]

- Barnard, N.D.; Cohen, J.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Gloede, L.; Jaster, B.; Seidl, K.; Green, A.A.; Talpers, S. A low-fat vegan diet improves glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in a randomized clinical trial in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1777–1783. [↩]

- The Three Mechanisms of Satiety [↩]

- Diet Reverses Type 2 Diabetes – How Long Have We Known This? [↩]

- Diabetes – Wheat VS Chickpea & Lentil Pasta [↩]

- Vegetarian Diets and the Risk of Diabetes [↩]

- Current Diabetes Treatment – Practice or Malpractice? [↩]

- Turmeric Proven To Fight Cancer & Diabetes [↩]

- Plant-based Diets & Diabetes [↩]

- Low-Fat Plant-Based Diets Help to Prevent Type 2 Diabetes [↩]

- Diabetes – The Medical Facts. WARNING – Disturbing Images [↩]

- Can The UK Government Really Combat Child Obesity? [↩]

- England’s Obesity Hotspots [↩]