I had a recent email asking me whether there really was any problem with swapping nasty old butter for cholesterol-lowering coconut butter. Well, let’s see, shall we?

Saturated Fat Content

- Coconut oil contains around 90-95% saturated fat (765 kcal/100g)

- Coconut butter contains around 60-65% saturated fat (540 kcal/100g)

- Dairy butter contains around 50% saturated fat (450 kcal/100g)

- Beef fat & Lard contain around 40-45% saturated fat (360 kcal/100g)

What’s the problem with saturated fat?

Let’s see what various authorities think…

“Eating a lot of saturated fat can increase the levels of cholesterol in your blood. Having high cholesterol can increase your risk of heart disease, which includes heart attack and narrowed arteries (atherosclerosis).”

Heart UK (The Cholesterol Charity)

“HEART UK advises people who want to lower their blood cholesterol to avoid using coconut oil in cooking and certainly not use it as a dietary supplement. Creamed and desiccated coconut contain around 60-70% coconut fat should also only be consumed occasionally or in small amounts as part of an overall healthy diet….The Cholesterol Charity wishes to correct the misleading claims being made in the press…claiming coconut oil helps lower blood cholesterol and have even suggested taking coconut oil as a dietary supplement. Coconut oil contains about 85% saturated fatty acids mainly as lauric and myristic acid which potently raise both total cholesterol and low density lipoprotein cholesterol more than other fatty acids (1,2,3,4).”

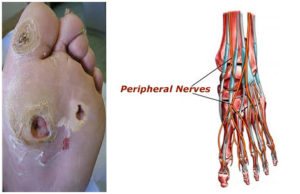

“Saturated fat is considered harmful to health. Studies have shown that high saturated fat intake may raise the risk of:

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Bacterial vaginosis

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery lesions

- Decreased male fertility

- Dementia

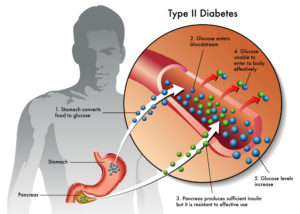

- Diabetes

- Hardening of the arteries

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High cholesterol levels

- Intestinal lining breakdown

- Kidney problems

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- Periodontal disease

- Skin aging and wrinkling

- Stroke…”

Dr Greger goes on to ask

“…coconut oil. Harmful? Harmless? Or, helpful? In terms of what it does to our cholesterol, it is as harmful as butter.”

PCRM (Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine)

“According to the American Heart Association, consuming saturated fat raises cholesterol levels in your blood, increasing risk for cardiovascular problems and Alzheimer’s disease. Setting aside saturated fat can also decrease your risk for obesity, diabetes, and cancer.”

“…replacing dietary saturated fats with ‘good carbs’ such as fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, reduced the risk of cardiovascular disease.”

So, in light of the foregoing, does this mean I consider saturated fat and especially coconut oil/butter to be our number one public enemy?

No, not at all.

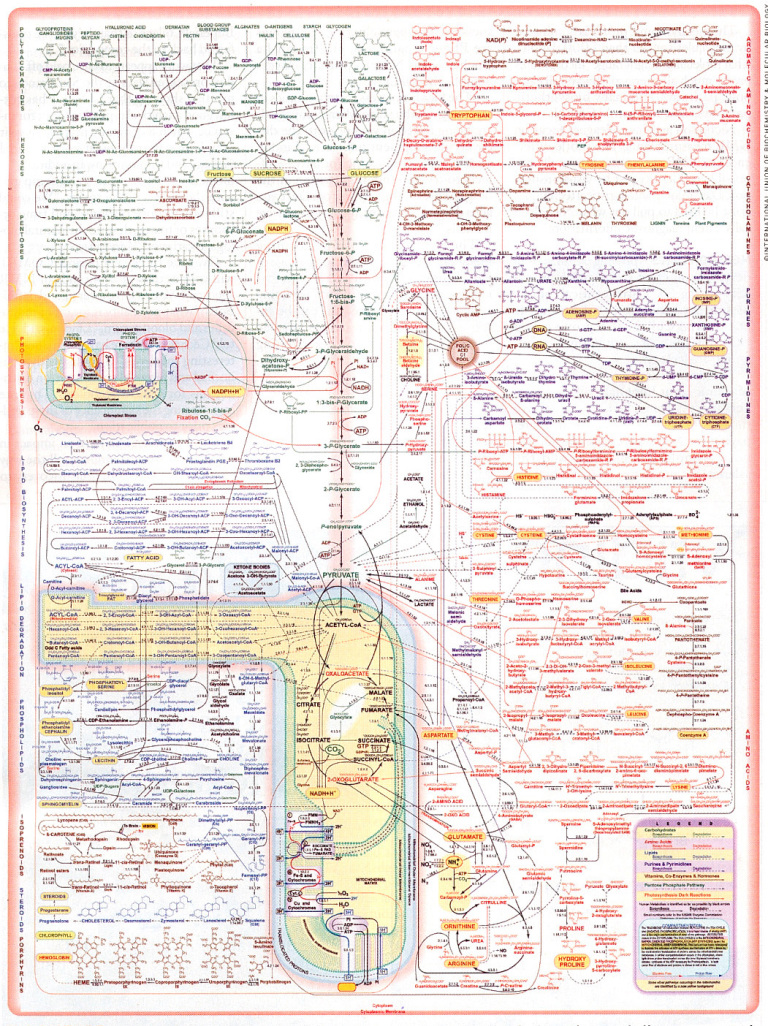

Focusing on any individual food “fragment”, whether it be a vitamin, mineral or an extracted oil from olives or organic Free Trade coconut butter, is a reductionist approach to nutrition that, in my opinion, is simply misguided. Concentrating on the individual harms or benefits of any individual part of our diet at the expense of stepping back and looking at diet as a whole is the reason that we have drifted into the pandemic of obesity and other diet-related chronic diseases.

Of course, if someone held my arm up my back and forced me to decide whether I would recommend eating coconut butter or an animal butter, I would have to say do NOT eat the animal product; but this would be like forcing me to decide whether I would recommend smoking cigars or smoking pipes! Without any doubt, I would say that it is better to smoke neither.

I believe exactly the same when talking about deciding between animal fats/oils and plant fats/oils – eat neither.

Why would I recommend anything to my clients, family or friends other than the diet that has repeatedly been shown to be the optimal diet for human health and longevity – a whole food plant-based diet.

And the emphasis here in on the word “whole”. The whole plant. Not the oil. The human body understands what a whole food is – it has been surviving and evolving on whole plant foods for millions of years. The body simply does not understand what concentrated and isolated components of plants are, let alone what to do with isolated animal or commercially altered and processed components. The body is used to the whole food (macronutrients, micronutrients and fibre) so that it can digest and absorb what it requires and safely excrete toxins and surplus nutrients as it sees fit.

Shock the system with isolated and concentrated saturated fat, or pretty much any other fragment of food, and the body cannot maintain homeostasis without a cost being paid right down at the cellular level – from the endothelial cells lining blood vessels to adipocytes bulking up that adipose fat around your waist (and your heart!)

“People eat food. Studies focusing on the health impact of differing amounts of saturated fat intake often fail to look at what the subjects are actually eating. Many foods that are low in saturated fat are still unhealthy. Therefore, what you eat instead of foods high in saturated fat is also critical…Not surprisingly, when you replace an unhealthy diet with an unhealthy diet, they both look about the same…if you replace saturated fat with plant-based foods, people do better.”

Replacing unhealthy animal foods with unhealthy plant foods might have some benefits, but you just have to look at an overweight and diabetic vegetarian or vegan to know that jumping out of the BBQ into a deep-fried tofu frying pan is no solution if you want optimal health.

“…animal-based protein is more hazardous than lipids (cholesterol and fatty acids)…Unsaturated fats (PUFAs) are susceptible to tissue damaging oxidation, and saturated fat is not…[which] cause aging and increases cardiovascular disease and cancer…plant oils experimentally promote cancer much more than does saturated fats—that’s right. This is an experimental observation that is at least 30-40 years old…this mainly refers to added oils-isolated from plant sources. It does not refer to the oil within those plant-based foods because plants contain lots of antioxidants to keep the tissue damaging effects of ROS [reactive oxygen species] under control. In my opinion, this is a primary reason for avoiding consumption of added oils. Another reason for avoiding these oils is their contribution to total calorie intake which displaces, in effect, the consumption of calorie-containing whole, plant-based foods.”

So, in summary, my considered opinion is that if a person is really concerned about what food they put in their bodies – if they really want to be healthy and do all they can to weigh the balance in favour of a long and useful life – then forget about debating which food fragment is better than another, just transition to the only diet that has been proven to reverse heart disease and many other chronic diseases – one that is based exclusively on whole food plants.

I will leave the final word on added oil (ANY oils, including coconut oil or coconut butter) to Dr Esselstyn:

References

1. Sundram K, Hayes KC, Siru OH (1994) Dietary Palmitic Acid Results in Lower Serum Cholesterol Than Does a Lauric-Myristic Acid Combination in Normolipemic Humans. Am J Clin Nutr 59, 841-846.

2. Temme EHM, Mensink RP, Hornstra G (1996) Comparison of the effects of diets enriched with lauric, palmitic or oleic acids on serum lipids and lipoproteins in healthy men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 1996; 63: 897-903.

3. Zock P L, de Vries J H, Katan M B (1994) Impact of Myristic versus palmitic acid on serum lipid and lipoproteins levels in health men and women Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1994;14:567-575.

4. Sanders TA (2013) Reappraisal of SFA and Cardiovascular Risk. Proc Nutr Soc, 72(4), 1-9.