A recent report in the Daily Telegraph1 reported that GP’s are no longer able to cope with the ‘tidal wave‘ of patients coming to them with multiple diseases. This is symptomatic of what the modern Western diet is doing to our populations – when the dietary intake is unhealthy, the whole body becomes unhealthy.

I have gone into some detail elsewhere2 about the difference between the reductionist and wholistic approach to health care: the former treats individual symptoms of so-called individual diseases with individual pharmaceutical/surgical ‘solutions’, while the latter regards the human organism as a whole and aims to treat all the causes of disease via dietary changes.

The following is a summary of some of the main points made in article interspersed with additional research findings.

- GPs are struggling to cope with a “tidal wave” of ever younger patients with multiple health problems, fuelled by unhealthy lifestyles, experts have warned.

- The Academy of Medical Sciences said the number of older patients with at least two conditions has risen by almost 50 per cent in a decade.

- Diseases “once almost unheard of” at a young age are increasingly being diagnosed:3

- Allergies 4 . While it is possible that parents are increasingly attuned to food allergies, it turns out that hospitalisations for severe food allergies is the main diagnosis that has increased substantially over the last two decades.

- Type 2 diabetes 5 . The rate of this disease has been rising in recent decades, both in the US and in Europe. The disease, if left untreated, is fatal – it is hard to miss or over-diagnose.

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) 6 . Severe bowel disease has been increasing in children, most notably since 1990. Two autoimmune diseases, UC (ulcerative colitis) and CD (Crohn’s disease), appear to be on the rise in children.

- Neurodevelopmental Illnesses 7 . The rates of ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, and neurodevelopmental disability have been increasing. Exposure to certain pesticides and dietary habits during pregnancy are among known risk factors for neurodevelopmental disorders, including lower IQ and impaired motor skills.

- Coeliac Disease 8 . This is another autoimmune disease that has increased in children. In a study that examined blood banked since 1974, it was found that the presence of antibodies characteristic of coeliac disease has, in fact, been doubling every 15 years since that time. This trend began before the introduction of GM food, and has continued since.

- Obesity 9 10 “Obesity is likely to supersede tobacco as the biggest cause of premature death. England has some of the worst figures and trends in obesity compared with the rest of Europe. Rising obesity prevalence is an international crisis that has the potential to overwhelm health care resources as well as creating enormous human suffering and social cost.“

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD)9 . “Overweight and obesity is a major public health concern that includes associations with the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors during childhood and adolescence as well as premature mortality in adults.“

- Prof Stephen MacMahon11 , chairman of The Academy of Medical Sciences working group, said Britain was among countries seeing a “massive increase” in the number of patients suffering multiple conditions.

- Around one in three Britons over the age of 50 are now estimated to suffer from multiple health problems – amounting for at least 15 million people.

- The trend could not just be attributed to the ageing nature of the population, researchers said, warning that increasing levels of obesity were fuelling diseases such as diabetes and heart disease at an ever younger age.

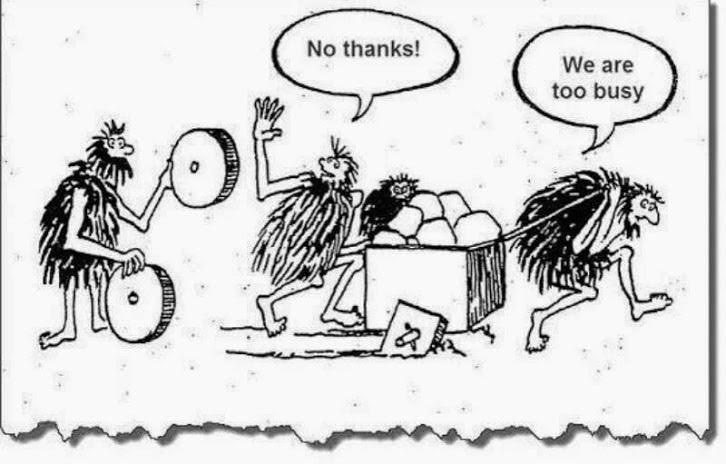

- The average GP consultation is just 10 minutes. This is insufficient to deal with the growing numbers of patients with several health complaints. Prof. MacMahon said “It’s extremely difficult to manage a patient with half a dozen diseases in 10 minutes. What happens is multiple consultations each focusing on the individual diseases.“

- The health service is not set up to care for the needs of rising numbers of patients suffering chronic conditions, often fuelled by unhealthy lifestyles.

- Millennials are set to be the fattest generation on record, with obesity causing nine in ten cases of type 2 diabetes.

- The average person aged 65 is likely to have three or more health conditions – rising to between five and seven among those aged 85 and over.

- Dr Lynne Corner, from the Newcastle University Institute for Ageing and Faculty of Medical Sciences said health services needed to be reorganised around the needs of those with multiple health conditions. “It can be a full time job being a patient,” she said. “It’s not unusual for someone to have five different appointments on five different days with five different teams and that can be really difficult to manage.”

Joe’s Comments

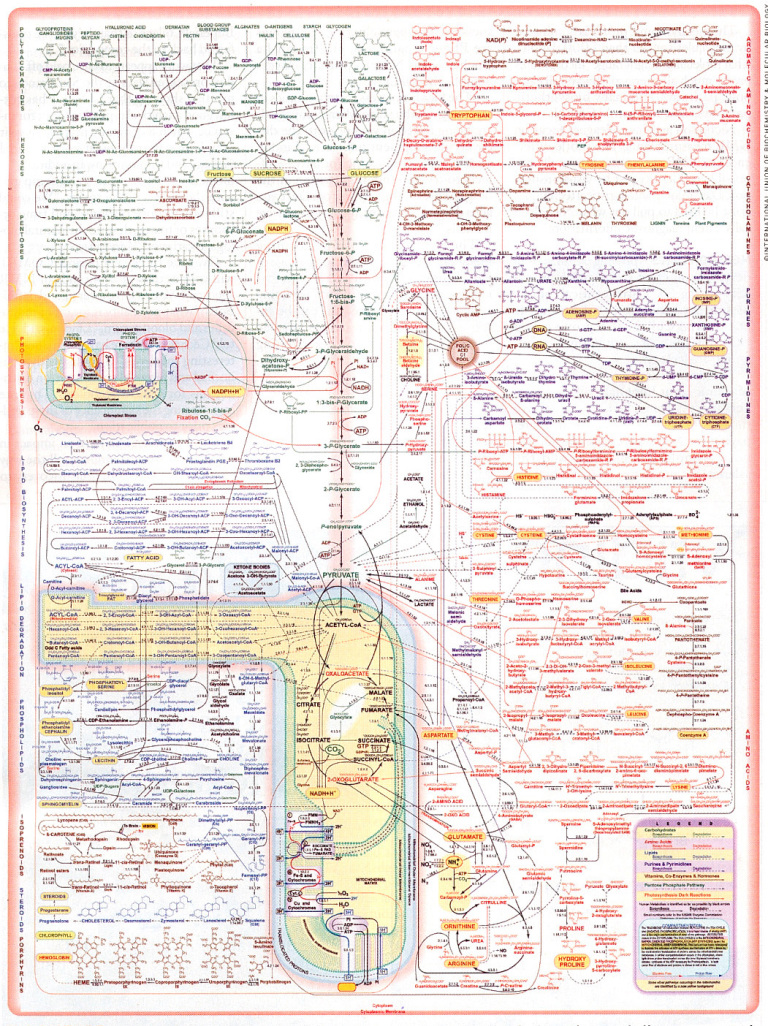

The wholistic approach to the human organism looks at each system, organ, tissue and cell as being linked together in an infinitely complex network. Affecting one part, affects the others. There is no such thing as an isolated health event, and so there is no sense in trying to treat individual and isolated diseases as though they are somehow independent and exist in isolation.

The thing that comes into contact with our bodies in the most intimate way is food and drink. Nothing else touches it for molecule by molecule interaction with us – both physiologically and psychologically. Yes, we can breathe toxic air or smoke and touch toxic substances, but the intimate contact that the food we put into our mouths has with every one of the billions of cells in our bodies (and trillions of bacteria in our guts) is incomparable.

We Are what we EAT – in a very real sense. But when we go to see out doctor, how many of us are asked about what we eat? Not many! And this is at best negligent and at worst criminal, in view of the wealth of research data showing that diet is the leading cause of almost all modern chronic non-communicable diseases.12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

So when a newspaper article like this appears, can we expect the responses of the various sections of society affected by it to be reductionist or wholistic? Let’s see…

The reductionist response (where the aim is to treat individual symptoms rather than the actual cause/s):

- Doctors and Hospitals: Health workers might complain that not enough money is being spent on the health service. Doctors may demand more money and time to see each patient, and hospitals may demand more staff.

- The Public: People might blame the government or say that there needs to be a crack-down on waste in the health service.

- Politicians: Opposition MP’s will say they could sort out this problem with better care systems and larger injections of cash. Government MP’s will claim that it is inefficiencies in the surgeries and hospitals, or make some general remarks about it being a complex issue that requires a costly and gutless public enquiry.

The wholistic response (where the aim is to treat the actual cause/s and not the individual symptoms):

- Doctors and Hospitals: All health workers are educated about the compelling mountain of research data that shows a processed, animal-based diet causes the vast majority of chronic non-communicable diseases while a whole food plant-based diet prevents and cures them. All trainee doctors are given substantial training in nutrition.

- The Public: People visiting their doctors or hospitals with chronic non-communicable diseases are given primary dietary advice before any other pharmaceutical or surgical interventions are suggested.

- Politicians: MP’s advocate for national and international campaigns to educate their citizens about the benefits of WFPB diet and the harm of the SAD (standard American diet). Government health policy responds to the latest factual research findings on the causes of chronic non-communicable diseases and aims to prevent the problems in the first place rather than tinker with ineffective “solutions” once the problems have developed. All fast-food is highly taxed in the same way as is done with tobacco. Governments stop receiving any funding or contributions from Big Pharma (Merck etc) or Big Food (the likes of PepsiCo, Nestlé and Tyson Foods etc).

The fat is hitting the fan now. Before long the fan will stop turning and a solution will have to be found. Whether it will be a dietary solution in the first instance is questionable; but, in the end, truth will out and, if our species is able to continue, a whole food plant-based dietary solution will be accepted as the intelligent norm rather than the weird exception.

References

- GPs can’t cope with ‘tidal wave’ of patients with multiple diseases by Laura Donnelly, health editor. 19 APRIL 2018 [↩]

- Wholism vs Reductionism – Not Just a War of Words [↩]

- Top Five Childhood Diseases on the Rise – GMO Science. [↩]

- Bethell CD, Kogan MD, Strickland BB, Schor EL, Robertson J, Newacheck PW. A national and state profile of leading health problems and health care quality for US children: key insurance disparities and across-state variations. Acad Pediatr. 2011 May-Jun;11(3 Suppl):S22-33 [↩]

- Lipman TH, Levitt Katz LE, Ratcliffe SJ, Murphy KM, Aguilar A, Rezvani I, Howe CJ, Fadia S, Suarez E. Increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes in youth: twenty years of the Philadelphia Pediatric Diabetes Registry. Diabetes Care. 2013 Jun;36(6):1597-603 [↩]

- Malaty HM, Fan X, Opekun AR, Thibodeaux C, Ferry GD.Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among children: a 12-year study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Jan;50(1):27-31 [↩]

- Halfon N, Houtrow A, Larson K, Newacheck PW. The changing landscape of disability in childhood. Future Child. 2012 Spring; 22(1):13-42 [↩]

- Tack GJ, Wieke H, Verbeek M, Schreurs W, Mulder CJJ. The Spectrum of Celiac Disease: Epidemiology, Clinical Aspects and Treatment. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 7, 204 (2010) [↩]

- Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Amna Umer, George A. Kelley, Lesley E. Cottrell, Peter Giacobbi, Jr, Kim E. Innes, Christa L. Lilly. BMC Public Health. 2017; 17: 683. Published online 2017 Aug 29. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4691-z. PMCID: PMC5575877 [↩] [↩]

- The rising prevalence of obesity: part B—public health policy solutions. Maliha Agha, Riaz Agha. Int J Surg Oncol (N Y) 2017 Aug; 2(7): e19. Published online 2017 Jun 22. doi: 10.1097/IJ9.0000000000000019. PMCID: PMC5673155 [↩]

- Professor Stephen MacMahon FMedSci. Principal Director, The George Institute for Global Health; Professor of Medicine and James Martin Professorial Fellow [↩]

- Prev Med. 2017 Apr;97:1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.12.044. Epub 2016 Dec 29. Vegetarian diet and all-cause mortality: Evidence from a large population-based Australian cohort – the 45 and Up Study. Mihrshahi S, Ding D, Gale J, Allman-Farinelli M, Banks E, Bauman AE [↩]

- Food groups and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Lukas Schwingshackl Carolina Schwedhelm Georg Hoffmann Anna-Maria Lampousi Sven Knüppel Khalid Iqbal Angela Bechthold Sabrina Schlesinger Heiner Boeing. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 105, Issue 6, 1 June 2017, Pages 1462–1473, https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.117.153148. [↩]

- Low-Carbohydrate Diets and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Hiroshi Noto , Atsushi Goto, Tetsuro Tsujimoto, Mitsuhiko Noda. Published: January 25, 2013https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055030 [↩]

- Public Health Nutrition: 15(4), 663–672 doi:10.1017/S1368980011002151. A bean-free diet increases the risk of all-cause mortality among Taiwanese women: the role of the metabolic syndrome. Wan-Chi Chang*, Mark L Wahlqvist, Hsing-Yi Chang, Chih-Cheng Hsu, Meei-Shyuan Lee, Wuan-Szu Wang and Chao A Hsiung. Submitted 14 February 2011: Accepted 25 June 2011: First published online 7 September 2011 [↩]

- Heather Fields, Denise Millstine, Neera Agrwal, Lisa Marks. Is Meat Killing Us? The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 2016; 116 (5): 296 DOI: 10.7556/jaoa.2016.059 [↩]

- Mortality – Article on nutritionfacts.org [↩]

- JAMA Intern Med. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 Jul 22. Published in final edited form as: JAMA Intern Med. 2013 Jul 22; 173(14): Fat intake after diagnosis and risk of lethal prostate cancer and all-cause mortality. Erin L. Richman, ScD, Stacey A. Kenfield, ScD, Jorge E. Chavarro, MD ScD, Meir J. Stampfer, MD DrPH, Edward L. Giovannucci, MD ScD, Walter C. Willett, MD DrPH, and June M. Chan, ScD [↩]

- Do Vegetarians Live Longer Than Health Conscious Omnivores? Dr John McDoougall’s Health & Medical Center. [↩]

- Animal Protein Linked to Death. August 1, 2016. By Thomas Campbell, MD [↩]