In Part 2 we will look at the design of scientific studies. Here, in Part 1, we will look at the scientific method.

Part 1 – Scientific Method

As you and I very well know, there are a bewildering range of different opinions about nutrition in general and, in particular, about what constitutes the ideal diet for human beings.

But how do we decide which opinion to trust? How can we be certain about what is just opinion and what is actually true?

I believe that we have to trust in an approach that is well summed up by Professor T Colin Campbell:

“In my realm of thinking, as far as research is concerned, I’d like to talk about science being an art of observation, basically pursuing a truth. Not necessarily ever finding a truth, but pursuing the truth, and in the process actually gathering evidence to a point where we have so much evidence, let’s say, for a certain point of view that then enables us to make decisions about ourselves, or about the society.” (1.)

This would rely on the use of a scientific method that can be duplicated and tested over and over again by other researchers if necessary in order to either verify or falsify the approach used, the data collected and the conclusions drawn.

I would suggest that there are 8 stages involved in a reliable scientific method. And this would then provide us with the sort of results that we could trust more than mere opinions – whether these opinions are expressed by friends and family, in newspapers and magazines, on social media or internet sites, in TV documentaries or news programmes:

The Scientific Method in Eight Stages

Stage 1 – Ask a question

Example: Are UK vegans especially at risk of vitamin D deficiency compared with the general population?

Stage 2 – Conduct background research

This would involve reviewing all published scientific literature for studies that establish a link between the vegan diet and vitamin D deficiency.

Stage 3 – Construct a hypothesis

Example: Make the prediction that it is more likely that vegans will have a vitamin D deficiency than the general population, based on the hypothesis that those who do not eat animal products (considered the major dietary source of vitamin D), and who also do not get enough exposure to sunlight because of the UK climate, may be more at risk.

Stage 4 – Test the hypothesis

The scope of this stage will depend on the amount of grant funding there is available. For instance, blood results might be compared between a cross-section of 50 vegans and 50 non-vegans if funding is low, but the sample might be increased to, say, 10,000 members of each group is funding is high. Naturally, the larger the sample size, the more reliable the results will be.

Stage 5 – Analyse the data and draw conclusions from it

This will require statistical analysis and justifications for whatever conclusions are drawn from the data relating to the populations analysed and the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency.

Stage 6 – Consider the conclusions and, if necessary, construct a new hypothesis

Example: it may be revealed from the data that vegans are much less at risk of vitamin D deficiency than was hypothesised in stage 3. Indeed, let’s say that the data revealed the unexpected finding that there was a widespread vitamin D deficiency within both groups studied – vegans and non-vegans; and that a particular group at risk was found within the females of Asian communities in the north of England and in Scotland. These findings might then suggest to the researchers that further research is needed. This might be research that, for instance, aims to establish a more accurate description of the scale of the problem; aims to discover the best ways of preventing/treating vitamin D deficiency; whether government/NHS campaigns are needed; or whether initial focus needs to be on the groups already identified as most at risk in the north of England and Scotland.

Stage 7 – Share the results of the research

The findings along with every detail of the research (the people who conducted it, the methods used, etc) would be published in a peer-reviewed journal. This would allow other scientists to review and comment on the study.

Stage 8 – Repeat the research

This might happen many times in order to check and re-check aspects of the research and the validity of the conclusions drawn. Eventually, if the research is repeated time and time again, and the same results are found by different researchers from different professional backgrounds and different countries, then it is likely that the findings could be described as proven facts or proven theories, depending on the nature of the research itself.

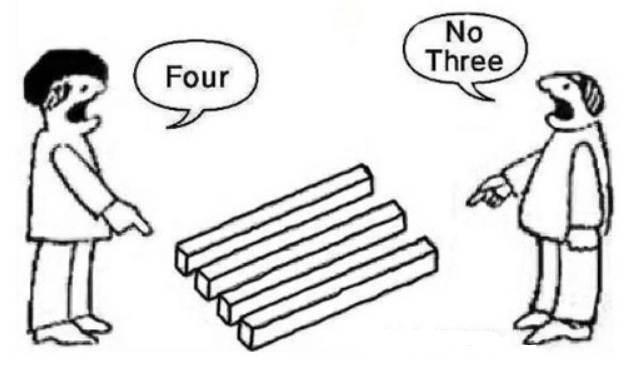

Whilst this is a rather simplistic view of the scientific method, it may help us to decide the reliability of an opinion we may already hold ourselves or that we may come across during our day-to-day life. A rule of thumb is to reserve any claim of certainty about an opinion until, as Dr Greger repeatedly says, it ‘s “put to the test”.

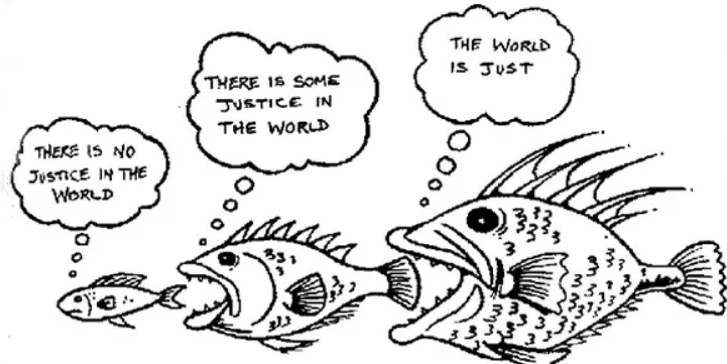

Finally, what is interesting in Professor Campbell’s quote above is that he does not talk about needing to establish “truth”; rather, we just need to know that we have done all we can to honestly and reliably establish the maximum amount of evidence in support of our opinion, even if this involves doing all we can to actively disprove our own opinion.

In my experience, it seems to be only those with strong religious convictions or hidden agendas who claim 100% certainty and will not consider the possibility that they are mistaken.

Thanks to bryanridgley.com for the images

References

- T Colin Campbell, CNS601 – Nutrition and Society, Module 2 Towards a New Paradigm, eCornell Certificate in Plant-Based Nutrition, 2018.