This is a basic overview of the macronutrients that make up a healthy balanced diet. If you know all this stuff already, there’s probably little point in reading this blog; but if you’re new to nutrition or want a refresher course, it might be of some interest.

Blog Contents

The Big Three

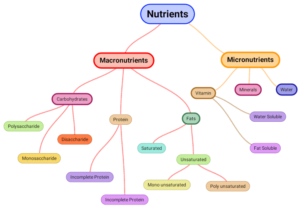

Nutritionists traditionally talk about three macronutrients:

- Carbohydrate

- Fat

- Protein

In addition to these, sufficient and appropriate fluid, micronutrients, minerals and vitamins complete the picture of what constitutes a healthy balanced diet.

Carbohydrate

Carbohydrate is the major energy source for many important bodily functions, including the nervous system, brain and working muscles. It’s a central source of vitamins (for instance, the B vitamins) and provides dietary fibre – important for its role within the digestive system, as well as for helping to control weight and protecting against chronic diseases such as diabetes, certain cancers and cardiovascular disease. See here for why fibre is so important.

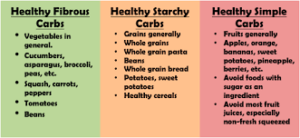

The Three Types of Carbohydrate

- Dietary fibre (soluble and insoluble)

- Starch (polysaccharides – more complex bonding of simpler sugars found in plant food such as bread and rice)

- Sugars (monosaccharides – fructose, galactose, glucose, and disaccharides – lactose, maltose and sucrose).

Galactose and lactose can be found in milk, glucose can be found in honey, and the remaining simple sugars can be found in plant foods – such as fructose in fruit, maltose in bread, glucose in honey and sucrose in small amounts in sugar beets and in unhealthy quantities as an additive to many processed foods.

Starchy foods, rather than foods high in simple sugars, are the ideal basis of our meals since they allow a slow release of sugars that the body can use as energy without having the problems associated with insulin spikes and the conversion of excess glucose (the product of starch digestion) being stored as fat within the adipose tissue.

The UK government recommends around 50% of total calorie intake should come from total carbohydrates. This would mean that a person requiring 1,600 kcals per day would be expected to aim for a daily intake of around 180 g – 260 g of carbohydrate; while one who requires 2000 kcals per day would be expected to aim for a daily intake of somewhere around 225 g – 325 g of carbohydrate. Naturally, these should come from whole plant foods and not from processed foods or as sugar added to homemade meals and beverages.

However, the reality is very different from this in the vast majority of cases. Only in a WFPB diet would you expect to find almost all carbohydrates in their natural state – within the fruit or vegetable, rather than extracted from it and added to “processed concoctions”.

If you are on a healthy and varied non-SOS WFPB diet already, you may notice that you consume considerably more than the UK government recommendations. Personally, I notice that the percentage of carbohydrate in my own diet and that of my clients is usually as much as 70-80%. This is in line with the recommendations of Drs T Colin Campbell, Michael Greger, Nathan Pritikin, Dean Ornish and John McDougall.

What are Carbohydrates?

Carbohydrates are composed of hydrogen, oxygen and carbon, with hydrogen and oxygen usually in the same ratio as in water (i.e. 2:1). The chemical formula for the biological molecule of a carbohydrate can be generalised as Cm(H2O)n, where C is carbon, H is hydrogen, O is oxygen, and the value of m can be different from that of n.

Fat

Fat, found in both plant and animal foods, provides the most energy per gram of the three macronutrients – 9 kcal/g as opposed to protein and carbohydrate which each contain 4 kcal/g. And, by the way, alcohol contains 7 kcal/g, so don’t think that your glass of red wine is going to be a low-fat option!

The UK government recommends daily fat intake should contain no more than 31.5% . Dr T Colin Campbell recommends around 12-15% maximum – and, of course, this is largely unsaturated fats that derive only from whole plant foods. Excess dietary fat intake will generally lead to fat storage within the body (for instance, below the skin, in adipose tissue, in the liver and even in the muscles).

There are two types of dietary fat:

- Saturated

- Unsaturated

There are two major types of unsaturated fat:

- Monounsaturated

- Polyunsaturated

A healthy diet would replace saturated fats, as well as harmful trans-fats, with unsaturated fats; thereby encouraging a healthy ratio of LDL and HDL cholesterol.

Animal foods are by far the largest source of saturated fat (including meat, dairy and fish). Palm oil, cocoa oil, coconut oil and avocados are some of the few plant foods that also contain saturated fat. Trans-fats are a common component of baked goods and fast/processed foods and snacks, being formed from the partial hydrogenation of oils into more solid fats. It is strongly advised that you consume ZERO amounts of added oils (even organic extra virgin olive oil).

Watch this video where Dr Caldwell B Esselstyn talking about why we should consume no added oil.

In relation to fat intake, it is common for nutritionists to recommend that a healthy diet will tend to replace full-fat foods with lower-fat alternatives – such as reduced-fat milk instead of full-fat milk. When it comes to a WFPB diet, there is not so much need to exclude all plant-based saturated fats for most people; however, Drs Ornish, Esselstyn, McDougall etc insist on very low levels of fat (especially saturated fats) in diets for those individuals suffering from diet-related diseases such as CVD, hypertension, obesity and hypercholesterolemia.

Fats are, however, important for health, and an optimal intake of the appropriate quantity and type of fats is essential for many physiological functions, including:

- Digestion and absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K)

- Cell growth

- Thermal insulation

- Organ protection from impact damage

- Production of certain hormones

As with carbohydrates and proteins, a variety of healthy fat sources in appropriate ratios should be consumed in order to ensure that the diet is balanced. This would entail ensuring that the correct ratio between omega-3 fatty acids (for instance, found in flaxseeds and walnuts) and omega-6 fatty acids (for instance, found in nuts and seeds), as well as, to a lesser extent, omega-7 fatty acids (for instance, found in tuna and macadamia nuts) and omega-9 fatty acids (for instance, found in hazelnuts and walnuts).

Dietary fats are mainly composed of triglycerides (complex molecules with a backbone of glycerol and three chains of fatty acids), as well as other components such as carotenoids, cholesterol, phospholipids and sterols. Like carbohydrates, dietary fats consist of carbon, oxygen and hydrogen.

Protein

Proteins are the building blocks of our bodies and are essential for every cell in the body and for the body to be able to grow, maintain and repair itself. Unlike carbohydrate and fat, protein is not stored in large quantities by the body. Also, while protein can be used as an energy source, it’s generally only used for energy production when carbohydrate and fat reserves are depleted or unavailable.

The result of this is that it will represent a much small percentage of the total daily calories that the body needs – Dr T Colin Campbell recommends somewhere between 8 and 12% (around 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight) depending on age, health status and level of physical activity. However, there are other authorities that recommend calories from protein should be as much as 35% of the diet – with the high upper figure only relevant to those individuals who are extremely active – such as athletes, soldiers, etc. While it should be noted that too much protein (specifically animal protein) in the diet can lead to serious health problems – such as bone loss and kidney damage, sufficient protein is essential within a healthy balanced diet. Dr T Colin Campbell is very clear that protein intake above 12% of calories is dangerous to health. He points out, though, that for those starting out on a WFPB diet “I don’t argue for a 10% fat diet as the main starting point, rather, I begin with the view that a plant-based diet is optimal and it just so happens that this diet, when done right (good quality WHOLE vegetables, legumes, fruits and cereals), is low in fat as well as in protein.” (1.)

Found in animal and plant foods, there is normally no difficulty in meeting daily protein requirements if eating a WFPB diet, for instance:

- Dried kidney beans 24% protein

- Peanut Butter 25% protein

- Dried lentils 26% protein

While opinions vary, there appears to be a growing consensus of professional opinion that our total protein intake should include more plant-based sources than is common within the current western diet – a diet that has commonly become dependent on animal-based sources. Just as with carbohydrates and fats, it’s important to ensure that protein sources are varied in order to provide the range of micronutrients contained in different food sources.

I am happy to say that it is becoming less common now that you hear people asking “How do you plant-based eaters get your protein?” The truth about the best type of dietary protein is getting better known – as is the fact that animal protein has been shown again and again to be harmful to human health.

Essential & Non-Essential Amino Acids

Like carbohydrates and fats, proteins are composed of hydrogen, oxygen and carbon but, in addition, they also contain nitrogen. They are created through the combination of the 20 amino acids that the body requires. Of these 20, nine are termed ‘essential’ and the remainder are ‘non-essential’ to varying degrees.

Our body can synthesise non-essential amino acids from essential amino acids – the latter being those that our body cannot make at all or not in the quantities that we require to maintain optimal health; thus, they must be derived from the foods we eat. It has been commonly thought that animal foods contain all the essential amino acids, while only a few plant foods (e.g. soya and buckwheat) contain all the essential amino acids. The result of this is that animal sources are generally termed ‘complete’ with High Biological Value (HBV) and plant sources are generally termed ‘incomplete’ with Low Biological Value (LBV) – in addition, the term ‘limiting amino acid’ is applied to the amino acids that are missing from plant food groups (for instance, legumes are generally considered deficient in methionine, while rice is considered deficient in lysine).

Thus, it has been accepted opinion that those people eating a largely or wholly plant-based diet need to be very careful that they are getting all of the essential amino acids. The established means of achieving this focused on the need to combine different limiting amino acid-containing food groups within the same meal – for instance, combining lentils with rice to provide both methionine and lysine.

However, this “combining myth” is increasingly under attack as an underestimation of the nutrient power of a varied WFPB diet. As Dr Michael Greger and Dr John McDougall pointed out, there really are no plants that lack all the amino acids – except gelatin!

Although amino acids vary in their formulae, the formula of a protein is invariably RCH(NH2)COOH: where R is a group (a ‘side chain’) which can vary in structure and composition, C is carbon, H is hydrogen, N is nitrogen and O is oxygen.

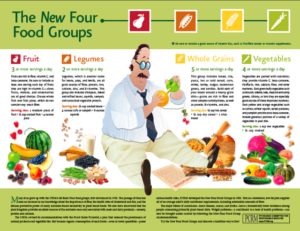

A Healthy Diet is a Varied Diet

There are general guidelines that should be followed to ensure that our diet is healthy: the diet should consist of a variety of different foods from the above macronutrient groups; meals should be eaten at regular times, with breakfast always being included (unless, of course, you are on a water fast or similar for health reasons); salt intake should be reduced to as low as possible (I advise less than 1 g/day and zero added salt); 6-8 glasses of water should be drunk daily; foods high in saturated fat should be monitored carefully; foods/beverages high in added sugar should be avoided altogether; fresh rather than processed foods should always be the chosen option; calorific intake should be in line with our activity levels, health status and age – although there really is less need to restrict calorific intake when on a WFPB diet when compared to all other diets, including vegetarian and vegan which can be highly calorific in the wrong type of calories.

References

- Fat & Plant-Based Diets. December 15, 2009. By T. Colin Campbell, PhD

- Low Carb Hot Air—Again, again and again! October 6, 2014. By T. Colin Campbell, PhD

- Optimum Nutrition Recommendations. September 12th, 2011. By Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

- High Carbohydrate Diets. Nutrition Australian – Nutrition fact Sheet Revised 2006. By Dr Dean Ornish

- The Eatwell Plate. UK Government Dietary Recommendation 2016

- Reference Intakes Explained. NHS Choices 2017

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Health Topic by Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

- Essential Facts about Fats. September 2, 1998. By Alan Goldhamer, D.C.

- Omega-9 in Happy Healthy Long Life. July 4 2008

- The Protein-Combining Myth. April 25th, 2016 Volume 30. By Michael Greger M.D. FACLM

- Plant foods have a complete amino acid composition. Circulation. 2002 Jun 25;105(25):e197; author reply e197. By J McDougall

- Alan Goldhamer, dc: Water Fasting—The Clinical Effectiveness of Rebooting Your Body. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2014 Jun; 13(3): 52–57. PMCID: PMC4684131. PMID: 26770100. Craig Gustafson