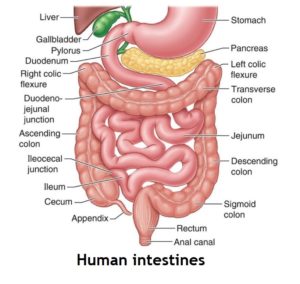

We’ve looked previously 1 at recent research revealing that any amount of alcohol intake is associated with certain types of cancer. We’ve also looked in some detail at how important bacteria (the microbiota 2 ) in our intestines 3 4 5 6 7 8 , bladder 9 and mouth 10 are for our physical and mental health. But what about the effect of alcohol (beer, wine and spirits) on the health of our microbiota?

You can find any amount of industry-funded research extolling the benefits of having a glass of red wine (that it contains polyphenols like resveratrol 11 , for instance). You will hear ‘conventional wisdom’ that it’s good to have “all things in moderation“.

But the microbes 12 within our bodies don’t listen to such pleasant reassurances.

Increasing amounts of research is providing us with a clearer understanding of how our favourite tipple affects the precious microbiota, which in turn has significant effects on our short- and long-term health.

Let’s get the alcoholics out of the way

However you want to define an alcoholic, it’s not going to be a shock to anyone that their microbiota are going to suffer if they consume vast quantities of alcohol, either on a regular basis of moderate to high intake or in less regular ‘binges‘ of high intake. And this is what’s shown in the following research.

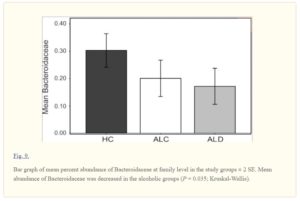

A May 2012 study 13 compared the microbiota composition of groups of a non-alcoholic control group and an alcoholic test group (including individuals with and without alcoholic liver disease).

Study results

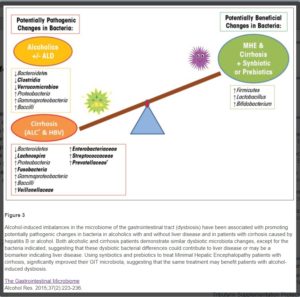

Dysbiosis (also called dysbacteriosis) refers to a microbial imbalance or maladaptation. This study found marked differences in the balance of various species/families of microbiota between the healthy control group (HC), those alcoholics without alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and those alcoholics with liver disease (ALD):

In this particular chart, the bacteria family called Bacteroidaceae, generally thought of as being beneficial to health, can be seen as reduced in the ALC and further reduced in the ALD group. There were additional differences found in the ratio of other dysbiotic and nondysbiotic bacterial communities between members of the two alcoholic groups (ALC and ALD) – including decreases in Clostridia and increases in Bacilli and Gammaprotoebacteria in those alcoholics described as having dysbiotic microbiota.

Study conclusion

“…the community composition of the dysbiotic cases is very different from those within the nondysbiotic cases, suggesting an overall disarray of the gut bacterial microbiome in the dysbiotic cases…we show that chronic alcohol consumption is associated with altered dysbiotic microbiota composition in a subset of alcoholics. We report that the alcoholics with dysbiosis had lower median abundances of Bacteroidetes and higher ones of Proteobacteria 14 . When the study subjects are examined according to study group, the alcoholic groups had a reduction in abundance of Bacteroidaceae.”

Thus, not all alcoholics studied had such unhealthy microbiota that they could be defined as dysbiotic; however, all alcoholics (ALC and ALD) had less ‘good’ and more ‘bad’ bacteria in their guts than the non-alcoholic control group (HC). The health effects of this type of imbalance have been shown in previous blogs (referenced above) to be linked to a wide range of diseases.

Further research on general alcohol consumption

A 2015 review 15 looked at the effect of alcohol consumption on the microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT).

The authors considered that alcohol-induced changes in the composition (quantitative and qualitative) and metabolic function of the GIT microbiota are likely contributors to:

- alcohol-induced oxidative stress

- intestinal hyperpermeability 16 to luminal bacterial products

- endotoxemia 17

- subsequent development of alcoholic liver disease (ALD)

- other organ pathologies

- increased GIT inflammation

- systemic inflammation

- tissue damage

- as well as other diseases

The reviewers recommend that gut-directed interventions, such as probiotic 18 and synbiotic 19 modulation of the intestinal microbiota, are solutions that should be considered and evaluated for the prevention and treatment of alcohol-associated pathologies.

Study conclusions

The researchers state that: “Chronic alcohol consumption causes intestinal dysbiosis in both rodent models and humans. Dysbiosis in the intestinal microbiota may contribute to the pathogenesis of liver disease…”

There’s no precise definition of ‘chronic’ in this study; thus, I’m left uncertain about whether it ranges from those who enjoy a couple of glasses of wine every evening to those who either regularly or occasionally consume vast quantities of alcohol.

Whatever the definition, they conclude that chronic consumption:

- alters intestinal barrier function, which is shown to lead, for example, to

- gut leakiness

- production of proinflammatory & pathogenic microbial products

- negatively-affected liver metabolic pathways 20

“…Thus, understanding the effect of alcohol on intestinal microbiota composition, may lead to a better understanding of its future functional activity, with the ultimate goal to restore intestinal microbiota homeostasis.”

Discussion

How much and how often we need to drink alcohol in order to start causing a leaky gut is something that this study does not specifically cover. Thus, so far, those of us who consider that we are not alcoholics, but simply enjoy a regular or occasional drink, don’t really need to worry about all this stuff. But we still have more research to look at before we can reassure ourselves so easily… After all, the working assumption of WFPB nutrition is that it’s wise to be suspicious of anything that’s not a whole food – and alcoholic drinks are certainly not whole foods.

Since this latter study looked at ways in which probiotics can be manufactured and sold (for profit, of course), it’s worth pointing out that good healthy plant food already contains all the prebiotics and probiotics that most people require. All whole plant food comes with millions of beneficial bacteria which are usually all the probiotics we need; and all unprocessed plants come pre-packed with all the fibre we normally need – and prebiotics are simply types of fibre found only in plant foods, and never in animal foods. Indeed, we saw previously 21 that there are concerns about the safety and efficacy of commercially-prepared probiotics 22 .

Alcohol & Leaky Gut

A 2003 study 23 looked at how alcohol consumption leads to disturbances in the intestinal absorption of nutrients, including several vitamins. The inhibition of the absorption of sodium and water caused by alcohol consumption contributes to the tendency in heavy drinkers to develop diarrhoea.

The study points out that even a single episode of heavy drinking can result in “…duodenal erosions and bleeding and mucosal injury in the upper jejunum [the part of the small intestine between the duodenum and ileum]…The mucosal damage caused by alcohol increases the permeability of the gut to macromolecules. This facilitates the translocation of endotoxin and other bacterial toxins from the gut lumen to the portal blood, thereby increasing the liver’s exposure to these toxins and, consequently, the risk of liver injury.”

They conclude that “..recent experimental studies support the assumption that alcohol significantly modulates the mucosal immune system of the gut.”

These findings on the effects of single episodes of binge drinking (which is defined as having 4 or more alcoholic drinks within a short period of time) have been supported by additional studies 24 .

Discussion

It’s not just chronic alcoholics who can experience leaky gut; it appears that the weakening of the delicate intestinal membrane, and thus the passage of toxins into the bloodstream, can happen after just one heavy drinking session. There’s no indication in this study about the effects of moderate but regular consumption of alcohol, nor of which type of drink (wine, beers, spirits) have the most damaging effects.

Gut microbiota and leaky gut

It appears that a major part of the reason why alcohol consumption can lead to a leaky gut is because of the alterations alcohol makes to the gut microbiota (or gut flora, as it’s also called). This can lead to ‘bacterial translocation’ 25 which, in turn, can cause inflammatory changes in the liver and elsewhere within the body.

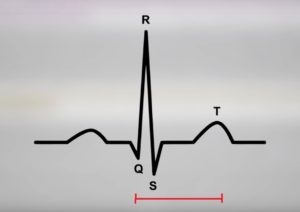

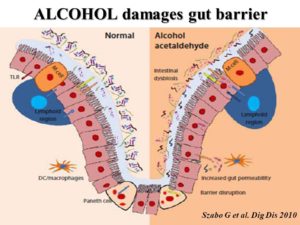

A 2008 study 26 considered the mechanisms involved when alcohol exposure leads to increased intestinal permeability. This is shown in the diagram below:

They point out that alcohol exposure has the ability to promote growth of Gram negative bacteria in the intestine. This is important because it may lead to the accumulation of endotoxins 27 . In addition, alcohol metabolism by Gram negative bacteria and intestinal epithelial cells 28 can result in accumulation of acetaldehyde 29 , which in turn can increase intestinal permeability to endotoxins.

They also point out that alcohol-induced generation of nitric oxide may also contribute to increased permeability to endotoxin. The endotoxin, having permeated the gut membrane, passes to the portal vein which, in turn, carries endotoxin to the liver where it binds to Kupffer cells and initiates a cascade of events leading to teh production of TNF-α (Tumour Necrosis Factor-α is a cell signalling protein (cytokine) involved in systemic inflammation) and subsequent liver injury.

And the damage does not end there. Endotoxin that escapes to the general blood circulation may then induce injury to other organs. For instance, a part of TNF- α produced in the liver may reach to intestine via bile duct or general circulation and further increase intestinal permeability to endotoxin.

Discussion

The health of the liver is closely related to the health of our gut bacteria. The above explains some of the mechanisms involved in liver and other organ damage due to the gut leakage as a result of alcohol consumption. Again, there is no clear definition of the quantity or frequency of alcohol consumption that’s needed in order to trigger these mechanisms.

Location matters

A February 2016 study 30 , discussed in some detail in a Scientific American article 31 adds more information about the process by which alcohol consumption (particularly heavy consumption) negatively affects the microbiome. The study found that: “Disease often depends not on the presence or the total amount of an organism in the gut but rather on location, which in this case is the gut mucosa.”

They did experiments on mice and found that if alcohol is given to the mice, some important genes (Reg3b and Reg3g) are downregulated 32 . The result of this is that they then produce significantly less of the antimicrobial molecules that can protect the gut against gram-negative and gram-positive organisms.

The mice given alcohol developed more (bad) bacteria in their guts and more severe liver disease compared with normal wild-type mice whose Reg3b and Reg3g genes had not been affected by alcohol.

Location is important in humans as well as in mice

The researchers also looked at samples of human gut tissue taken during colonoscopies: “Sure enough, heavy drinkers had more bacteria in their mucosa, just as was seen in the mouse model. That suggested the alcohol was suppressing production of the naturally protective peptides.”

When bacteria gets into the mucosa, they can then leak through the epithelium wall into the bloodstream (leaky gut): “The balance between microbes and immune defenses was upended and more bacteria were able to migrate through the gut wall into the body, eventually traveling through the bloodstream to the liver. T cells attacked the invaders and the resulting inflammation scarred the liver.” They are going to further investigate which type of microbes are most dangerous if they migrate into the bloodstream; at the moment, this study is basically looking at quantity rather than type of microbes in the mucosa.

Study conclusion

“A product delivered to the middle of the gut may have little benefit; it may have to be packaged in a way to hone in on the mucosa. Potential treatments, however, are years if not decades away. Until then the best thing people can do is reduce alcohol consumption to lessen possible damage to the body.”

Discussion

The researchers were looking for some genetic or pharmaceutical means of treating genetic/microbial changes caused by heavy alcohol consumption, and their findings suggest that simply using a treatment that flushes the gut, without being targeted into the mucosa, will have little effect. As you can see from their conclusion, they don’t expect any magic pill to be invented before years, possibly decades, have passed. So their suggestion about erring on the side of caution by reducing alcohol consumption seems sensible.

What they don’t look at is whether diet can reverse or in any way affect the situation where a heavy drinker has inadvertently caused a microbial build up in the mucosa within their gut. My suspicion is that the body is capable of repairing itself if it is given the appropriate nutrients (without continuing with the onslaught of the damaging alcohol, of course) over an extended period of time – weeks to months of a non-SOS WFPB diet.

Study shows a few days of alcohol use causes damage

Plenty of studies 33 have looked at long-term alcohol use, whilst a March 2017 study 34 focused on the changes that would happen if mice were given a controlled amount of alcohol for a period of 10 days.

Akkermansia bacteria reduced by alcohol consumption

The number of Akkermansia bacteria were found to be dramatically reduced by alcohol consumption. Other studies 35 corroborate this finding.

So what?

This genus of bacteria in gut barrier maintenance is disrupted by alcohol.

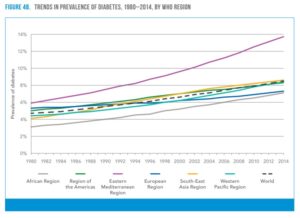

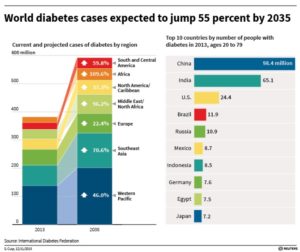

A parallel decrease in population numbers of Akkermansia has also been found to be decreased in mouse models of obesity and type-2 diabetes, while supplementation with this bacteria has been shown to alleviate the burden of metabolic dysfunction 36 .

Study conclusion

“This study supports the hypothesis that the gut microbiota are impacted by alcohol consumption…We conclude that gut microbes influence liver inflammation, neutrophil infiltration 37 and liver steatosis 38 following alcohol consumption and these data further emphasize the gut-liver axis, even in early alcohol-induced inflammation.”

Discussion

The latter study seems to suggest that even relatively short-term heavy alcohol use can start the process of liver damage. The liver appears to be able to repair itself to some extent if alcohol consumption stops, but the latter process causes scarring of liver tissue that cannot be reversed. Over time, this reduces the amount of the liver that can function.

Alcohol consumption and pneumonia susceptibility

It’s not just the liver that becomes damaged when alcohol consumption causes gut dysbiosis. A June 2017 study 39 revealed how the natural defences of the heart and lungs against the bacteria that causes pneumonia (Klebsiella pneumoniae) are greatly weakened by excessive alcohol consumption. Once again, as with so many bodily reactions, this condition originates in changes to the gut microbiota.

Mice on a binge

The tests undertaken on mice showed that binge-drinking over a 48-hour period was sufficient to create a lung burden caused by an increased infection of the K. pneumoniae bacteria.

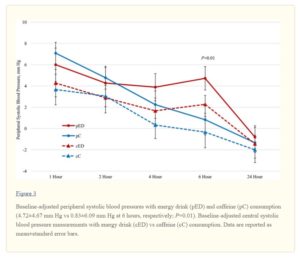

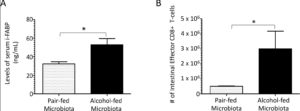

The following chart show the significant differences in specific symptoms of dysbiosis (intestinal fatty acid binding protein and and T-cells) between the pair-fed 40 control group and the alcohol-fed group:

Discussion

The latter study once again emphasises the damage caused when the gut microbiota is altered through even short-term chronic alcohol consumption.

All alcohol in your drinks is ethanol

It’s easy to imagine that one drink is ‘safer’ than another – for instance, those who drink wine consider that it may be less harmful than beer, and those who drink beer might think it’s a healthier option than drinking spirits; however, the alcohol they each contain is the same thing – ethanol.

All chronic alcohol ingestion leads to bacterial overgrowth and dysbiosis in the small and large intestine of animals and humans 41 42 43 44 45 . Studies in mice have shown that ethanol reduces the bacteria phylum Firmicutes 46 and the genus Lactobacillus 44 , while the species Enterococcus 47 , Akkermansia, Corynebacterium, and Alcaligenes increase after alcohol administration 44 45 46 . Chronic ethanol consumption also markedly reduces amino acid metabolism, and perturbs the metabolism of steroid, lipid, carnitine 48 , and bile acid 49 . Additionally, after consuming ethanol, intestinal levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), as well as saturated long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) are lower 50 51 .

Oral microbiota & alcohol

It’s not just the gut microbiota that gets damaged by alcohol, as was demonstrated in an April 2018 study 52 , the bacteria in our mouths also struggle to cope with ethanol intake.

A large number of human subjects were included in this study, and the researchers looked at the effects of all types of alcoholic drink (wine, beer and spirits) and also at different levels of consumption, from non-drinkers, through to infrequent and heavy drinkers.

Study results

They found that: “…alcohol consumption, and heavy drinking in particular, may influence the oral microbiome composition.” In particular, they found that alcohol consumption is associated with decreased abundance of Lactobacillales (‘good’ bacteria), and increased levels of the potentially pathogenic bacteria, Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria (‘bad’ bacteria). They considered that depletion of Lactobacillales, thought to be important for good oral health, may promote growth of other alkaline-tolerant bacteria 53 .

Mechanisms involved

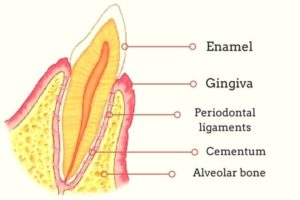

Ethanol may indirectly increase certain bacterial taxa by decreasing Lactobacillales thereby increasing pH, as mentioned above, or by inhibiting the antimicrobial properties of saliva and by disturbing the host-microbial balance. Additionally, alcohol could impair neutrophil function (contributing to bacterial overgrowth and increased bacterial penetration), reduce monocyte production of inflammatory cytokines (allowing for microbial proliferation), and have adverse effects on teeth (stimulating bone resorption and suppressing bone formation) [and the periodontium.

Long- and short-term damage

Both acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) ethanol exposure were considered by this study to lead to functional changes in saliva, including decreased flow rate and impaired output of total protein, amylase, and electrolytes.

Different types of alcoholic drink

Whilst the study found some differences between the oral microbiota of non-drinkers and wine drinkers – specifically, wine-drinkers had a richer and different microbial profile from non-drinkers, with a decreased abundance of the phyla Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, the family Peptostreptococcaceae) – the study concluded that: “Because our study had limited numbers of subjects who exclusively consumed beer, wine, or liquor, further study is required to disentangle the differential effect of each type of alcoholic beverage on oral microbial composition.” They did, however, point out that any variations that may occur between different types of alcoholic drink, probably derive simply from the relative percentage of ethanol contained.

An article in NewsMedical.net 54 pointed out that some of the different species found in drinkers compared with non-drinkers included the species, Actinomyces, Leptotrichia, Cardiobacterium, and Neisseria. “These strains have been known to raise the risk of head and neck cancers as well as a cancers of the food pipe or esophagus and pancreas….heavy drinkers showed more pronounced presence of these bacteria. The bacteria interacted with the alcohol as it was broken down by the body and this led to preferential growth of certain strains of the bacteria. The strains of healthy bacteria Lactobacillales were however much reduced.”

Discussion

It would be interesting to compare the effects of drinking 100% pure ethanol with lower percentages. It would be no surprise to me to find that the changes to microbiota, wherever we are looking within the body, would be to a large degree proportional to the percentage of ethanol consumed. Naturally, there would be some bacterial and other physiological changes caused by added ingredients (such as other chemicals from grapes, barley, hops, rye, etc) within each drink; but the effects of the ethanol may well be relatively consistent, depending on percentage of content.

Psychiatric disorders, alcohol and the microbiome

A July 2018 study 55 confirmed what we have already discussed in a previous blogs 3 4 , namely the essential role that the body’s microbiome plays in our psychological well-being. This particular study considered the growing body of evidence showing that alcohol consumption increases brain levels of certain molecules that signal to our body’s immune system that something is wrong, resulting in neuroinflammation. Similar results had already been found in studies on other animal models 56 .

Our central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord, has certain immune responses when it senses danger. The researchers note that the microbiota play a pivotal role in this process and affect central neurochemistry and behaviour: “Disruption of or alterations in the intimate cross-talk between microbiome and brain may be a significant factor in many psychiatric disorders. Alterations in the composition of the microbiome, so called dysbiosis, may result in detrimental distortion of microbe-host homeostasis modulating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.” Heavy alcohol consumption can play a significant causal role in dysbiosis and, in turn, dysbiosis and psychiatric disorders appear to be strongly linked.

Psychiatric pathologies associated with these changes in the community structure and function of the gut microbiota, include irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, and alcoholism.”

Study conclusion

“…emerging data suggests that alcohol induced alterations of the microbiome may explain reward-seeking behaviors as well as anxiety, depression, and craving in withdrawal and increase the risk of developing psychiatric disorders.”

Discussion

We probably all could have guessed that research would find alcohol can causes short- and long-term psychological changes; but maybe not so many of us knew that the trillions of bacteria within us are so intimately connected with this process.

Effects of just one alcoholic drink

We’ve mainly looked at chronic alcohol consumption, but when we looked above at the 2003 study 23 , we saw that even a single heavy drinking session (a so-called ‘binge’) can cause significant damage, including inducing a leaky gut. However, most of us would assume that negative psychological and psychological effects would be significantly less when we drink only a little alcohol infrequently.

10 symptoms of potential sensitivity to alcohol

Your gut may already be reacting (whether you are aware of it or not) to the quantities of alcohol you consume, if you:

- find it hard to lose weight and/or gain weight easily

- experience frequent constipation and/or diarrhoea

- flush easily, particularly during/after consuming alcohol

- suffer from acid reflux, ulcers, or other stomach acid problems

- have food allergies, seasonal allergies, or histamine issues

- have skin problems, for instance eczema, psoriasis, acne, or rashes

- have a history of hormone problems

- have an existing autoimmune disease, disorder, or other chronic health problem, including thyroid, adrenal, intestinal, digestive, or metabolic

- have an GIT (gastro-intestinal tract) condition, for instance SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth), dysbiosis, leaky gut, or coeliac disease

- have liver problems

The above is by no means meant to be a comprehensive list of possible associated conditions, nor is it meant to be a diagnosis; however, if you do drink alcohol and experience some of these effects, it might be worth taking a closer look at whether alcohol is playing a part.

Final thoughts

This has been a somewhat random and potted look at some of the studies relating to alcohol and the microbiota. For me, the take-home message is that consuming alcohol, in any form, is something we do because of its psychological effects (making us feel relaxed, giving us a buzz, allowing us to act with more confidence, or being able to forget our worries and feel temporarily less stressed).

However, I suspect that none of us would choose to put ethanol into our bodies if it had no effect at all on how we felt. Whilst this might seem an obvious point, it does have some significance. What if our bodies and minds were sufficiently healthy and strong that we didn’t need the effects that alcohol to ‘sustain’ or ‘refresh’ us? What if our diet and lifestyle continually fortified us, so that we could weather the usual stresses of life?

From my research and personal experience, eating the optimal diet, getting plenty of exercise, sleeping well, and finding mindful ways of sailing smoothly through the rough seas of daily life are four lifestyle options that link together and have the potential of providing that fortification. At the core of it, at least in my opinion, is a WFPB diet. It provides all the nutrients we need, while at the same time avoiding all the toxins and empty calories that come part-and-parcel with animal and processed foods. A WFPB diet also brings with it, the psychological benefits of knowing you are taking the most effective step in helping to protect the environment and to reduce animal suffering.

Finally, the very concept of a WFPB diet is that you eat whole plant foods. Alcohol, of course, is not a whole plant food. Thus, whether we choose to drink it or not, it’s worth remembering that a glass of wine, beer or our favourite spirit is, in effect, a processed food. This may not seem such a big issue, but a side-effect of the addictive nature of so many processed foods and drinks also applies to alcohol and, as such, they can easily replace optimally healthy foods and drinks.

It’s no coincidence that the things you crave most after a good drinking session are things like kebabs, crisps, cakes, sweets and not lentils, salad, apples and broccoli!

References

- No Amount of Alcohol Consumption is Safe [↩]

- Brief explanation of the difference between ‘microbiota’ and ‘microbiome’. Microbiota refers to the 100’s of different species of microbes (bacteria, fungi etc), while microbiome refers to the complete set of genes within these microbes. [↩]

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) & Gut Microbiota [↩] [↩]

- Gut Microbiota & Depression [↩] [↩]

- Fibromyalgia, Probiotics & Gut Microbiota [↩]

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS), Serotonin & Gut Microbiota [↩]

- Two Types of Gut Bacteria: Plant Eaters’ & Meat Eaters’ [↩]

- IBD / Crohn’s Disease / Ulcerative Colitis & WFPB Diet Part 5 of 5 [↩]

- Urinary Microbiome & Psychological Issues in Women with Overactive Bladder [↩]

- Oral Microbiota – Meat-Eaters & Plant-Eaters [↩]

- The Best Source of Resveratrol. Video by Michael Greger M.D. FACLM April 2nd, 2018 Volume 41 [↩]

- The human body is home of trillions of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other tiny organisms. These organisms are known as microbes. [↩]

- Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012 May 1; Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. Mutlu EA, Gillevet PM, Rangwala H, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, Engen PA, Kwasny M, Lau CK, Keshavarzian A. [↩]

- Proteobacteria include a wide variety of pathogens, such as Escherichia, Salmonella, Vibrio, Helicobacter, Yersinia, Legionellales, etc. [↩]

- Alcohol Res. 2015;37(2):223-36. The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: Alcohol Effects on the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota. Engen PA, Green SJ, Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Keshavarzian A. [↩]

- Wikipedia: Intestinal permeability. [↩]

- Definition of endotoxemia: The presence of endotoxins in the blood, which, if derived from gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria, may cause haemorrhages, necrosis of the kidneys, and shock. [↩]

- NHS: Probiotics. [↩]

- Definition of synbiotic: The term synbiotic is used when a product contains both probiotics and prebiotics. Because the word alludes to synergism, this term tends to be used for products in which the prebiotic compound selectively favours the probiotic compound. [↩]

- Metabolic pathways are a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell. The reactants, products, and intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are modified by a sequence of chemical reactions catalysed by enzymes. [↩]

- Concerns about processed probiotics. [↩]

- Culture Shock – Questioning the Efficacy and Safety of Probiotics. Michael Greger M.D. FACLM October 25th, 2017 Volume 38 [↩]

- Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003 Aug;17(4):575-92. Effect of alcohol consumption on the gut. Bode C, Bode JC. [↩] [↩]

- PLOS One: Acute Binge Drinking Increases Serum Endotoxin and Bacterial DNA Levels in Healthy Individuals. Shashi Bala , Miguel Marcos , Arijeet Gattu, Donna Catalano, Gyongyi Szabo. Published: May 14, 2014https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096864. [↩]

- Bacterial translocation is the passage of viable bacteria from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to extraintestinal sites, such as the mesenteric lymph node complex (MLN), liver, spleen, kidney, and bloodstream. [↩]

- Vishnudutt Purohit,a, J. Christian Bode,b Christiane Bode,b David A. Brenner,c Mashkoor A. Choudhry,d Frank Hamilton,e Y. James Kang,f Ali Keshavarzian,g Radhakrishna Rao,h R. Balfour Sartor,i Christine Swanson,j and Jerrold R. Turnerk. Alcohol, Intestinal Bacterial Growth, Intestinal Permeability to Endotoxin, and Medical Consequences. Alcohol. 2008 Aug; 42(5): 349–361. [↩]

- Definition of endotoxin: a toxin present inside a bacterial cell that is released when it disintegrates. [↩]

- Difference between epithelial and endothelial cells: Endothelial cells form the endothelium, a thin layer that coats the inner surface of blood vessels. The cells always lie attached to the vessel wall. The inner wall of the entire circulatory system is covered with endothelial cells. They act as an interface between the circulating blood and the vessel wall. The endothelium is one-cell-layer thick and also lies attached to the interior of the heart chambers. On the other hand, epithelial cells form the epithelium. This covers the outside portion of the body (the three layers of skin or epidermis), and also coats all the internal organs – including the liver, stomach, intestine, lungs, urethra, urinary bladder, and other organs of the body. Thus, epithelial cells provide a protective coating to the surface of the body and its internal tissues. [↩]

- Acetaldehyde is a product of alcohol metabolism which is more toxic than the alcohol itself. Acetaldehyde is created when the alcohol in the liver is broken down by an enzyme called alcohol dehydrogenase. The acetaldehyde is then attacked by another enzyme, acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, and another substance called glutathione, which contains high quantities of cysteine (a substance that is attracted to acetaldehyde). Together, the acetaldehyde dehydrogenase and the glutathione form the nontoxic acetate (a substance similar to vinegar). [↩]

- “Intestinal REG3 Lectins Protect against Alcoholic Steatohepatitis by Reducing Mucosa-Associated Microbiota and Preventing Bacterial Translocation.” Wang et al., Cell Host & Microbe 19, 1–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.003 [↩]

- Scientific American February 2016: Drinking Causes Gut Microbe Imbalance Linked to Liver Disease [↩]

- Definition of downregulation: Downregulation is the process by which a cell decreases the quantity of a cellular component, such as RNA or protein, in response to an external stimulus. [↩]

- Bull-Otterson L, Feng W, Kirpich I, Wang Y, Qin X, Liu Y, et al. Metagenomic analyses of alcohol induced pathogenic alterations in the intestinal microbiome and the effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53028. Epub 2013/01/18. pmid:23326376 [↩]

- PLOS One. Alcohol-related changes in the intestinal microbiome influence neutrophil infiltration, inflammation and steatosis in early alcoholic hepatitis in mice. Patrick P. Lowe , Benedek Gyongyosi , Abhishek Satishchandran, Arvin Iracheta-Vellve, Aditya Ambade, Karen Kodys, Donna Catalano, Doyle V. Ward, Gyongyi Szabo. Published: March 28, 2017https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174544. [↩]

- Wang L, Fouts DE, Starkel P, Hartmann P, Chen P, Llorente C, et al. Intestinal REG3 Lectins Protect against Alcoholic Steatohepatitis by Reducing Mucosa-Associated Microbiota and Preventing Bacterial Translocation. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19(2):227–39. Epub 2016/02/13. pmid:26867181 [↩]

- Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(22):9066–71. Epub 2013/05/15. pmid:23671105 [↩]

- Definition of neutrophil infiltration: Neutrophils are important disease-fighting white blood cells. Neutrophil infiltration is the diffusion or accumulation of neutrophils in tissues or cells in response to a wide variety of substances released at the sites of inflammatory reactions. [↩]

- Definition of liver steatosis: the infiltration of liver cells with fat, associated with disturbance of the metabolism by, for example, alcoholism, malnutrition, pregnancy, or drug therapy. [↩]

- PLOS Pathogens: Alcohol-associated intestinal dysbiosis impairs pulmonary host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Derrick R. Samuelson , Judd E. Shellito, Vincent J. Maffei, Eric D. Tague, Shawn R. Campagna, Eugene E. Blanchard, Meng Luo, Christopher M. Taylor, Martin J. J. Ronis, Patricia E. Molina, David A. Welsh. Published: June 12, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006426 [↩]

- Definition of Pair-feeding: This is a technique where the amount of food provided to a control group of mice is matched to that consumed by the experimental group, so as to determine the extent to which the effect of a treatment on body weight or body composition occurred independently of changes of energy intake. [↩]

- Bode JC, Bode C, Heidelbach R, Durr HK, Martini GA. Jejunal microflora in patients with chronic alcohol abuse. Hepatogastroenterology. 1984;31(1):30–4. Epub 1984/02/01. pmid:6698486 [↩]

- Casafont Morencos F, de las Heras Castano G, Martin Ramos L, Lopez Arias MJ, Ledesma F, Pons Romero F. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41(3):552–6. Epub 1996/03/01. pmid:8617135. [↩]

- Engen PA, Green SJ, Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Keshavarzian A. The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: Alcohol Effects on the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota. Alcohol Res. 2015;37(2):223–36. Epub 2015/12/24. pmid:26695747; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4590619. [↩]

- Hartmann P, Chen P, Wang HJ, Wang L, McCole DF, Brandl K, et al. Deficiency of intestinal mucin-2 ameliorates experimental alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58(1):108–19. Epub 2013/02/15. pmid:23408358; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3695050. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Yan AW, Fouts DE, Brandl J, Starkel P, Torralba M, Schott E, et al. Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53(1):96–105. Epub 2011/01/22. pmid:21254165; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3059122. [↩] [↩]

- Bull-Otterson L, Feng W, Kirpich I, Wang Y, Qin X, Liu Y, et al. Metagenomic analyses of alcohol induced pathogenic alterations in the intestinal microbiome and the effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53028. Epub 2013/01/18. pmid:23326376; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3541399. [↩] [↩]

- MCC C , NL L , CM F , JL G , D A , C G , et al. Comparing the effects of acute alcohol consumption in germ-free and conventional mice: the role of the gut microbiota. BMC Microbiology. 2014;14(1):240. pmid:25223989 [↩]

- Xie G, Zhong W, Zheng X, Li Q, Qiu Y, Li H, et al. Chronic ethanol consumption alters mammalian gastrointestinal content metabolites. J Proteome Res. 2013;12(7):3297–306. Epub 2013/06/15. pmid:23763674. [↩]

- Xie G, Zhong W, Li H, Li Q, Qiu Y, Zheng X, et al. Alteration of bile acid metabolism in the rat induced by chronic ethanol consumption. Faseb j. 2013;27(9):3583–93. Epub 2013/05/28. pmid:23709616; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3752538. [↩]

- Chen P, Torralba M, Tan J, Embree M, Zengler K, Starkel P, et al. Supplementation of saturated long-chain fatty acids maintains intestinal eubiosis and reduces ethanol-induced liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(1):203–14.e16. Epub 2014/09/23. pmid:25239591; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4274236. [↩]

- Ronis MJ, Korourian S, Zipperman M, Hakkak R, Badger TM. Dietary saturated fat reduces alcoholic hepatotoxicity in rats by altering fatty acid metabolism and membrane composition. J Nutr. 2004;134(4):904–12. Epub 2004/03/31. pmid:15051845. [↩]

- Microbiome. 2018 Apr 24;6(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0448-x. Drinking alcohol is associated with variation in the human oral microbiome in a large study of American adults. Fan X, Peters BA, Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM, Purdue MP, Freedman ND, Alekseyenko AV, Wu J, Yang L, Pei Z, Hayes RB, Ahn J. [↩]

- Bull-Otterson L, Feng W, Kirpich I, Wang Y, Qin X, Liu Y, Gobejishvili L, Joshi-Barve S, Ayvaz T, Petrosino J, et al. Metagenomic analyses of alcohol induced pathogenic alterations in the intestinal microbiome and the effect of lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53028. [↩]

- NewsMedical.net April 2018: Alcohol damages microbiome in the mouth [↩]

- Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018 Jul 13;85:105-115. Alcohol, microbiome, and their effect on psychiatric disorders. Hillemacher T, Bachmann O, Kahl KG, Frieling H. [↩]

- Am J Pathol. 2006 Apr; 168(4): 1335–1344. Alcohol Abuse Enhances Neuroinflammation and Impairs Immune Responses in an Animal Model of Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Encephalitis. Raghava Potula, James Haorah, Bryan Knipe, Jessica Leibhart,*Jesse Chrastil, David Heilman, Huanyu Dou, Rindha Reddy, Anuja Ghorpade, and Yuri Persidsky. [↩]