A 2019 Taiwanese study 1 recently reported on the results of two large-scale cohort studies which were analysed in order to establish whether following a vegetarian diet reduces the risk of developing gout, when compared with following a non-vegetarian diet.

Blog Contents

What is gout?

This subject has been covered extensively in a previous blog 2 so, in brief terms:

- gout is the most common inflammatory joint disease and is an important risk factor for hypertension, diabetes, kidney diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality 3 4 5 6

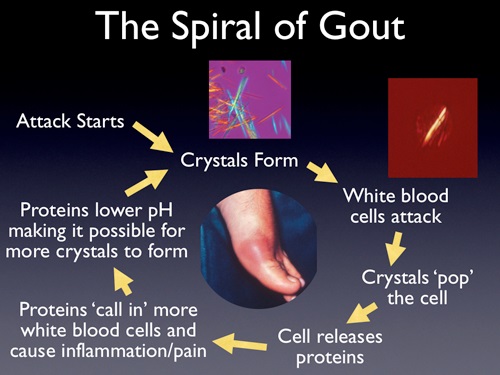

- gout pathogenesis begins with excess serum urate that forms monosodium urate crystals – a salt or ester of uric acid – in the joints, triggering gouty inflammation and resulting in excruciating pain 78

- cases of gout have doubled or tripled in many countries in the past decades 9 10 making it a serious public health threat which desperately requires preventive strategies

- Taiwan is particularly affected, with one of the highest incidences and prevalences of gout in the world 11

The study

Two cohort groups, representing almost 14,000 Taiwanese, were followed for between 7 and 9 years. They were divided into vegetarians (n=4684) and non-vegetarians (n=9251), and appropriate tests were undertaken to establish gout occurrence.

Study assumptions

- the standard therapeutic diet aimed at preventing/managing gout restricts purine intake which is metabolised into urate and contributes to one-third of the body’s total urate pool 12

- however, purine exclusion diets have only moderate urate-lowering effects and are generally regarded as an insufficient remedy 13

- the researchers considered that the ideal diet for gout prevention/management should be able to simultaneously reduce uric acid and inflammation, while preventing gout-associated comorbidities

- they conjectured that a vegetarian diet may be a promising dietary pattern to target multiple pathways in the gout pathogenesis, since:

- vegetarians avoid purine-rich meat/seafood, while consuming increased amounts of vegetables, whole grains, seeds and nuts 14 15

- plant foods contain polyphenols which potentially reduce uric acid via both an inhibition of xanthine oxidase16 activities and the enhancement of uric acid excretion 17

- plant foods contain phytochemicals which potentially attenuate the NLRP3 18 inflammatory pathway 19 20

- vegetarian diets have already been shown to reduce gout associated comorbidities, such as cardiovascular diseases 21 , diabetes 22 23 , and hypertension 24 25

Study results

“In these two prospective cohort studies, a Taiwanese vegetarian diet is associated with lower risk of gout. This association persists after controlling for demographic, lifestyle, cardiometabolic risk factors, and baseline hyperuricemia. This finding does not differ across subgroups of sex, lifestyle factors, or comorbidities.”

- it’s most likely that vegetarians experienced a lower risk of gout simply because they had lower uric acid levels since their diets avoid purine-rich meat and seafood – a diet which in prospective studies has been shown to increase gout incidence and recurrence26 27 28 29

- the results appear to go beyond the single effects of uric acid levels, since they were not consistently wide apart between all vegetarians and all non-vegetarians. The other potential factors influencing the reduction of gout in vegetarians may also be accounted for by the following:

- vegetarian diets have higher alkalinity which has been shown to facilitate more effective uric acid excretion than an acidic diet – i.e. one that is fish/meat-based 30

- vegetarian diets usually contain lower saturated fat, higher unsaturated fat and phytochemical-rich plant foods 14 15 31

- the latter may prevent inflammatory responses which trigger gout attacks by dampening the inflammatory activation of NLRP3 inflammasome 32

- fibre (high in plant-based diets) on its own, and when metabolised into short chain fatty acids by gut microbiota, has been shown to resolve inflammatory responses involved in gout attacks in mice 33 and in humans 34

Final thoughts

We saw in the previous gout blog 2 that there’s plenty of strong evidence to suggest that the best possible dietary option for gout-avoidance is a WFPB diet (with zero alcohol!). Of course, any diet which favours plant over animal foods will be of some benefit, and the more the latter is replaced with the former, the better in terms of gout-avoidance.

One interesting finding from this Taiwanese study relates to soy. Taiwanese vegetarian diets replace meat and seafood with soy products. But there appears to be a paradox here. Soy has a high purine content and has attracted an infamous reputation – even amongst health professionals – for causing gout 35 . However, contrary to this widely-held belief, the vegetarian diets with high soy content covered in this present Taiwanese study appear to lower gout risk.

And this is not the only study to show this. The researchers’ findings are consistent with the “Singapore Chinese Health Study” which found that soy was protective toward gout 27 .

A potential explanation for this rests in the fact that the potential of soy purines – mainly adenosine 36 and guanine 37 – to raise uric acid levels is considerably lower than those in meat and fish, which have a higher proportion of their purines in the form of hypoxanthine 38 39 40

A 2012 prospective study 41 of gout patients found that the impact of plant purine on gout attacks was significantly less than the purine from animal sources.

Finally, research suggests 42 that soy may have the ability to prevent gout through the inhibition of both the above-mentioned NLRP3 inflammatory pathway and the activity of the caspase-1 enzyme. The latter is an essential effector of inflammation, pyroptosis 43 , and septic shock 44 .

So, hurrah for the plants, boo hiss for meat and seafood, and don’t be shy about eating soy…

References & Notes

- Vegetarian diet and risk of gout in two separate prospective cohort studies. Chiu THT, Liu CH, Chang CC, Lin MN, Lin CL. Clin Nutr. 2019 Mar 27. pii: S0261-5614(19)30129-3. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2019.03.016. [↩]

- Gout, Uric Acid, Urea, Purines & Plant-Based Diets [↩] [↩]

- Bardin T, Richette P. Impact of comorbidities on gout and hyperuricaemia: an update on prevalence and treatment options. BMC Med 2017;15:123. [↩]

- Kuo CF, See LC, Luo SF, Ko YS, Lin YS, Hwang JS, et al. Gout: an independent risk factor for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:141e6. [↩]

- Choi HK, Curhan G. Independent impact of gout on mortality and risk for coronary heart disease. Circulation 2007;116:894e900. [↩]

- Teng GG, Ang LW, Saag KG, Yu MC, Yuan JM, Koh WP. Mortality due to coronary heart disease and kidney disease among middle-aged and elderly men and women with gout in the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:924e8. [↩]

- Desai J, Steiger S, Anders HJ. Molecular pathophysiology of gout. Trends Mol Med 2017;23:756e68. [↩]

- So AK, Martinon F. Inflammation in gout: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2017;13:639e47. [↩]

- Roddy E, Doherty M. Epidemiology of gout. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:223. [↩]

- Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Zhang W, Doherty M. Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:649e62. [↩]

- Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, See LC, Yu KH, Luo SF, Zhang W, et al. Epidemiology and management of gout in Taiwan: a nationwide population study. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:13. [↩]

- Fam AG. Gout: excess calories, purines, and alcohol intake and beyond. Response to a urate-lowering diet. J Rheumatol 2005;32:773e7. [↩]

- Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, Bae S, Singh MK, Neogi T, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1431e46. [↩]

- Chiu TH, Huang HY, Chiu YF, Pan WH, Kao HY, Chiu JP, et al. Taiwanese vegetarians and omnivores: dietary composition, prevalence of diabetes and IFG. PLoS One 2014;9:e88547. [↩] [↩]

- Orlich MJ, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Sabate J, Fan J, Singh PN, Fraser GE. Patterns of food consumption among vegetarians and non-vegetarians. Br J Nutr 2014;112:1644e53. [↩] [↩]

- Xanthine oxidase is a type of enzyme that generates reactive oxygen species. These enzymes catalyse the oxidation of hypoxanthine to xanthine and can further catalyse the oxidation of xanthine to uric acid. [↩]

- Mehmood A, Zhao L, Wang C, Nadeem M, Raza A, Ali N, et al. Management of hyperuricemia through dietary polyphenols as a natural medicament: a comprehensive review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017:1e23. [↩]

- J Inflamm Res. 2018 Sep 25;11:359-374. doi:10.2147/JIR.S141220. eCollection 2018. Spotlight on the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Groslambert M1,2,3,4,5, Py BF [↩]

- Joseph SV, Edirisinghe I, Burton-Freeman BM. Fruit polyphenols: a review of anti-inflammatory effects in humans. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2016;56:419e44. [↩]

- Tozser J, Benko S. Natural compounds as regulators of NLRP3 inflammasomemediated IL-1beta production. Mediat Inflamm 2016;2016:5460302. [↩]

- Crowe FL, Appleby PN, Travis RC, Key TJ. Risk of hospitalization or death from ischemic heart disease among British vegetarians and nonvegetarians: results from the EPIC-Oxford cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:597e603. [↩]

- Chiu THT, Pan W-H, Lin M-N, Lin C-L. Vegetarian diet, change in dietary patterns, and diabetes risk: a prospective study. Nutr Diabetes 2018;8:12. [↩]

- Tonstad S, Stewart K, Oda K, Batech M, Herring RP, Fraser GE. Vegetarian diets and incidence of diabetes in the adventist health study-2. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2013;23:292e9. [↩]

- Yokoyama Y, Nishimura K, Barnard ND, Takegami M, Watanabe M, Sekikawa A, et al. Vegetarian diets and blood pressure: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:577e87. [↩]

- Chuang SY, Chiu TH, Lee CY, Liu TT, Tsao CK, Hsiung CA, et al. Vegetarian diet reduces the risk of hypertension independent of abdominal obesity and inflammation: a prospective study. J Hypertens 2016;34:2164e71. [↩]

- Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med 2004;350: 1093e103. [↩]

- Teng GG, Pan A, Yuan JM, Koh WP. Food sources of protein and risk of incident gout in the Singapore Chinese health study. Arthritis Rheum 2015;67:1933e42. [↩] [↩]

- Williams PT. Effects of diet, physical activity and performance, and body weight on incident gout in ostensibly healthy, vigorously active men. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1480e7. [↩]

- Zhang Y, Chen C, Choi H, Chaisson C, Hunter D, Niu J, et al. Purine-rich foods intake and recurrent gout attacks. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1448e53. [↩]

- Kanbara A, Miura Y, Hyogo H, Chayama K, Seyama I. Effect of urine pH changed by dietary intervention on uric acid clearance mechanism of pHdependent excretion of urinary uric acid. Nutr J 2012;11:39. [↩]

- Rizzo NS, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Sabate J, Fraser GE. Nutrient profiles of vegetarian and nonvegetarian dietary patterns. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113:1610e9. [↩]

- Ralston JC, Lyons CL, Kennedy EB, Kirwan AM, Roche HM. Fatty acids and NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammation in metabolic tissues. Annu Rev Nutr 2017;37:77e102. [↩]

- Vieira AT, Galvao I, Macia LM, Sernaglia EM, Vinolo MA, Garcia CC, et al. Dietary fiber and the short-chain fatty acid acetate promote resolution of neutrophilic inflammation in a model of gout in mice. J Leukoc Biol 2017;101:275e84 [↩]

- Lyu LC, Hsu CY, Yeh CY, Lee MS, Huang SH, Chen CL. A case-control study of the association of diet and obesity with gout in Taiwan. Am J Clin Nutr

2003;78:690e701. [↩] - Messina M, Messina VL, Chan P. Soyfoods, hyperuricemia and gout: a review of the epidemiologic and clinical data. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011;20:347e58. [↩]

- Adenosine is a chemical that is present in all human cells. It readily combines with phosphate to form various chemical compounds including adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP). [↩]

- Guanine is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine. [↩]

- Hypoxanthine is a naturally occurring purine derivative. It is occasionally found as a constituent of nucleic acids, where it is present in the anticodon of tRNA in the form of its nucleoside inosine. [↩]

- Kaneko K, Aoyagi Y, Fukuuchi T, Inazawa K, Yamaoka N. Total purine and purine base content of common foodstuffs for facilitating nutritional therapy for gout and hyperuricemia. Biol Pharm Bull 2014;37:709e21. [↩]

- Clifford AJ, Riumallo JA, Young VR, Scrimshaw NS. Effect of oral purines on serum and urinary uric acid of normal, hyperuricemic and gouty humans. J Nutr 1976;106:428e50. [↩]

- Zhang Y, Chen C, Choi H, Chaisson C, Hunter D, Niu J, et al. Purine-rich foods intake and recurrent gout attacks. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1448e53. [↩]

- Bitzer ZT, Wopperer AL, Chrisfield BJ, Tao L, Cooper TK, Vanamala J, et al. Soy protein concentrate mitigates markers of colonic inflammation and loss of gut barrier function in vitro and in vivo. J Nutr Biochem 2017;40:201e8. [↩]

- (Pyroptosis is a highly inflammatory form of programmed cell death that occurs most frequently upon infection with intracellular pathogens and is likely to form part of the antimicrobial response. [↩]

- Septic shock is a potentially fatal medical condition that occurs when sepsis, which is organ injury or damage in response to infection, leads to dangerously low blood pressure and abnormalities in cellular metabolism. [↩]