Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD’s), such as ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), are autoimmune conditions where your immune system attacks your intestines. It’s thought that there’s no cure for Crohn’s disease, so all you can do is try to keep it in remission as long as possible between attacks. But can a plant-based diet help this debilitating disease? This is a complex topic, so it has been covered in three parts. This is part 1 of 5.

(See Further Notes, below, for a more detailed explanation of IBD, UC & CD)

Blog Contents

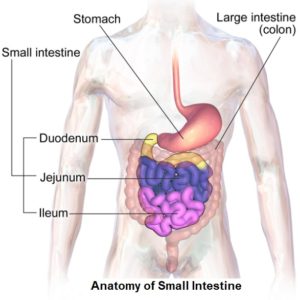

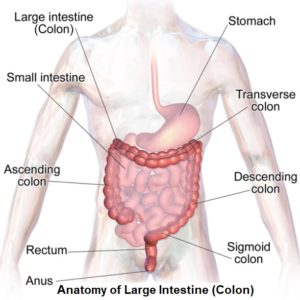

The Anatomy of the Intestines

Traditional Treatments

Sufferers are often put on anti-inflammatory corticosteroid drugs – e.g. prednisone, prednisolone, hydrocortisone, budsonide and mesalamine 1 2 as well as immunosuppressive drugs – e.g. azathioprine3 (Azasan, Imuran). mercaptopurine (Purinethol, Purixan), infliximab4 5 6 (Remicade, Inflectra, Remsima), adalimumab7 (Humira), certolizumab pegol8 9 (Cimzia), methotrexate (Trexall), natalizumab10 (Tysabri), vedolizumab (Entyvio), ustekinumab (Stelara).

When the drugs and (questionable) dietary changes – such as cutting out fibre and eating more protein – don’t work anymore 11 , sufferers can then find themselves in and out of the hospital, getting chunks of their intestines surgically removed.

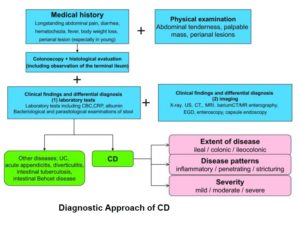

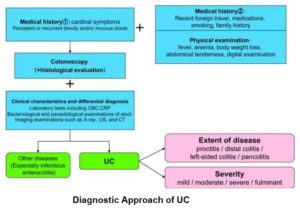

The following are the two diagnostic approaches for establishing the presence of CD and UC:

Inflammation

Since it’s the intestine itself that’s inflamed- and food travels through the intestines – it would seem ideal for researchers to see if intestinal inflammation can be treated by changing the diet.

Research12 13 has already clearly shown that many foods, including meat, cheese, fish, and animal protein in general increase the risk of developing IBD’s such as CD, while it’s been shown14 15 that plant foods reduce the risk.

Semi-Vegetarian Diets & CD

But what about research that looks at whether the anti-inflammatory power of plants can also treat conditions like CD and not just help to prevent them in the first place?

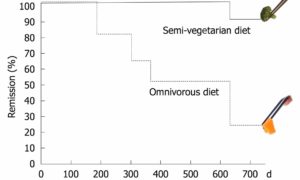

For two years, Japanese researchers16 followed a a number of CD patients who were in remission. The patients were split into two groups. One group was asked to continue eating their standard (omnivorous) diet, while the other group was asked to eat a semi-vegetarian diet—meaning in this case, vegetarian, except for half a serving of fish a week, and half a serving of other meat once every two weeks. N.B. this is not a WFPB no-SOS (added sugar, oil and salt) diet and they were only asked and not forced to follow the diet.

The results at 200 days into the study:

- 100% of the semi-vegetarian diet group were still in remission from any CD symptoms.

- Around 20% of the standard diet group had relapsed.

The results after 1 year:

- 100% of the semi-vegetarian diet group were still symptom free.

- 50% of the standard diet group had relapsed.

The results after 2 years:

- 92% of the semi-vegetarian diet group remained without any disease at all.

- Over 80% of the standard diet group had relapsed into the cycles of drugs, hospitalisations and surgery.

This was a significant finding and, remember, that this was only a marginally plant-based diet with no controls over whether the semi-vegetarian group members ate more animal foods or consumed unhealthy processed plant foods. Indeed, a sample menu within their research literature shows cow’s milk yogurt and eggs were still a part of the diet, and the protein level of 16% of caloric intake was higher than would be expected on a WFPB diet. Furthermore, the researchers could only rely on the individual testimonials about what and how much they ate – and, as we know, these are not always reliable indicators of an individual’s actual behaviour.

Nevertheless, the researchers claim that this is the best result in CD relapse prevention ever reported. And this includes all pharmaceutical and surgical interventions to date.

The following chart represents the relapse rates of the semi-vegetarian group and the standard (omnivorous) diet group:

Standard Results on Standard Diets

It’s thought17 that relapse rate in the above standard diet group is standard on standard diets, with most Crohn’s sufferers relapsing within a year or two. As Dr Greger says: “Most Crohn’s sufferers relapse within a year or two–unless, it seems, they start eating healthier.” 18

For Dr Michael Greger’s view19 , see the following video:

Part 2 will take a detailed look at research into dietary factors associated with IBD (CD & UC).

Further Notes20 on Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD), Crohn’s Disease (CD) & Ulcerative Colitis (UC)

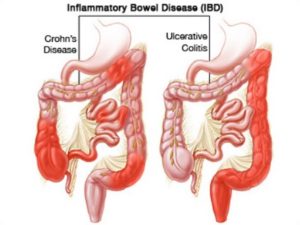

IBD refers to diseases of a chronic or remitting/relapsing intestinal inflammation. This guideline describes UC and CD as the major forms of inflammatory bowel diseases of unknown cause (aetiology). Both diseases develop complicated pathology, again with unknown causes, and mainly affect the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in various clinical symptoms.

UC and CD are collectively referred to as IBD because the two diseases share common or similar features; however, disease location, morphology (form and structure), and pathophysiology (physiological changes associated with a disease) are clearly different between them, and they are considered to be independent diseases. Moreover, it is necessary to classify them because diagnostic procedures, therapeutic interventions, and follow-up observation are somewhat different. Notably, it is called ‘IBD unclassified’ when colonic lesions have the features of IBD which cannot be classified as UC or CD.

Patients with IBD often experience impaired daily quality of life (QOL) since both diseases can appear at young ages and progress into repeated cycles of chronic relapse and remission throughout life.

UC is a diffuse non-specific inflammatory disease of unknown cause that continuously affects the colonic mucosa proximal from the rectum and often forms erosions and/or ulcers. It frequently repeats cycles of relapse and remission during its course and may be accompanied by extraintestinal complications. When it extensively affects the large intestine for a long period of time, a risk of developing cancer increases [a].

CD is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown cause, although there are theories: one theory suggests an abnormal immune response to gut bacteria; another suggests processed foods or recently emerged allergens may be responsible; additionally, there appears to be a genetic factor (gene NOD2) running in families.21 Other causal factors may include certain viral or bacterial infections, ethnicity, smoking and even the use of a treatment for acne scars (isotretinoin – although there are strong objections22 to this drug being responsible).

CD is characterised by discontinuously affected areas with transmural granulomatous inflammation (where intestinal walls are breached, resulting in an accumulation of immune cells called histiocytes – a type of tissue macrophage) and/or fistula (an abnormal connection between an organ and another structure). This is often referred to as a ‘leaky gut’, and as intestinal contents spill into the blood, and get attacked by white blood cells, the result may be all sorts of additional and serious health problems.

It can affect any region in the digestive tract from the mouth to the anus, but is more likely to involve the small intestine (the ileum) and large intestines (the colon and especially the ileocaecal valve) and the area around the anus (perianal region) [b]. The inflamed tissues become thick and swollen, and the inner surfaces of the digestive system may develop open sores (ulcers). Generally speaking it’s found in the colon some 30% of the time and 30% in the ileum/small intestine. Both sites have been shown, when taken together, to have an occurrence rate of approximately 40%.

CD is less common than UC. Both men and women are equally affected. CD can occur at any age but there may be peaks at 15 to 30 years old and between 50 and 70 years old. Even very young children can develop the disease. In fact, 20 per cent of CD patients are diagnosed before the age of 20. It has also been established that CD is more common among smokers. There are many more potential symptoms in CD than in many gastrointestinal diseases. Signs and symptoms tend to flare up multiple times throughout life.

The most common features of CD this condition are:

- Persistent diarrhoea

- Abdominal pain and cramping

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Anal problems

- Anaemia

- Fever

Some people with CD have blood in the stool from inflamed tissues in the intestine; over time, chronic bleeding can lead to a low number of red blood cells (anaemia). The inflammation in CD extends through the bowel wall leading to abscess formation or scarring and narrowing of the bowel known as stricture formation. In addition, it may develop extraintestinal complications in systemic organs such as the liver, joints, the skin, and the eyes. This makes CD a ‘multi-system’ or generalised disease.

In addition, symptoms will depend on the severity of the disease and which part of the bowel is affected.

Traditional nutritional opinion has been that there is no specific diet recommended for all patients with CD. Nutritionists and medical professionals have historically considered that general nutrition should concentrate on providing adequate macro- and micro-nutrients in an easily-absorbed form, especially after intestinal surgery. The object of management of the disease to date has been to treat periods of relapse in order to produce remission. The task then has been to maintain the disease in an inactive state. If complications develop they would then need to be treated specifically. The treatment of CD has always complex, difficult and has required specialist medical advice. Treatment has usually focused on a combination of dietary intervention and drugs. Because of the relative ineffectiveness of this approach, surgery has been required for the majority of patients.

The disease is named after Dr Burrill B Crohn, a New York doctor, who reported cases in the 1930’s.

The incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) is significantly increased in UC patients who have extensive lesions for a long period of time, and it is also known that the incidence of cancers in the small and large intestines, especially in the rectum and anal canal region, is high in CD patients. Therefore, an efficient surveillance strategy for cancer development is normally expected to be established by the patient’s doctor. IBD is considered to be a disease that does not significantly affects the patients’ life prognosis, although IBD patients have slightly shorter life prognosis compared to normal individuals.

This is a must-watch video ‘Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Crohns, and Colitis with Pamela A. Popper‘.

- Thomsen OO, Cortot A, Jewell D, et al: A comparison of budesonide and mesalamine for active Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 1999;340:370-374. [↩]

- Sandborn WJ, Löfberg R, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Campieri M, Greenberg GR. Budesonide for maintenance of remission in patients with Crohn’s disease in medically induced remission: a predetermined pooled analysis of four randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Aug;100(8):1780–7. [↩]

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. SONIC Study Group Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 15;362(15):1383–95. [↩]

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. SONIC Study Group Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 15;362(15):1383–95. [↩]

- Present DN, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al: Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1398-1405. [↩]

- Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al: Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:876-885. [↩]

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al: Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: The CHARM trial. Gastroenterology 2007;132:52-65. [↩]

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Stoinov S, et al: Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2007;357:228-238. [↩]

- Schreiber S, Khaliq-Kareemi M, Lawrance IC, et al: Maintenance therapy with certolizumab pegol for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 2007;357:239-250. [↩]

- Targan SR, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, et al. Natalizumab for the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: Results of the ENCORE Trial. Gastroenterology 2007;132:1672-1683. [↩]

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/crohns-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353309 [↩]

- Watzl B. Anti-inflammatory effects of plant-based foods and of their constituents. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2008 Dec; 78(6):293-8. [↩]

- Cundiff DK, Agutter PS, Malone PC, Pezzullo JC. Diet as prophylaxis and treatment for venous thromboembolism? Theor Biol Med Model. 2010 Aug 11; 7:31. [↩]

- Jantchou P, Morois S, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Carbonnel F. Animal protein intake and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: The E3N prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Oct; 105(10):2195-201. [↩]

- Maconi G, Ardizzone S, Cucino C, Bezzio C, Russo AG, Bianchi Porro G. Pre-illness changes in dietary habits and diet as a risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease: A case-control study. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep 14; 16(34):4297-304. [↩]

- Chiba M, Abe T, Tsuda H, Sugawara T, Tsuda S, Tozawa H, Fujiwara K, Imai H. Lifestyle-related disease in Crohn’s disease: Relapse prevention by a semi-vegetarian diet. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 May 28; 16(20):2484-95. [↩]

- Nash RA, McDonald GB. Crohn disease: remissions but no cure. Blood. 2010 Dec 23;116(26):5790-1. [↩]

- Treating Crohn’s Disease With Diet. Michael Greger M.D. FACLM. September 13th, 2012 [↩]

- https://nutritionfacts.org/video/achieving-remission-of-crohns-disease/ [↩]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5847182/ [↩]

- Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, et al: A frameshift mutation in NOD2 is associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature 2001;411:603-606. [↩]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3995201/ [↩]