Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD’s), such as ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), are autoimmune conditions where your immune system attacks your own intestines. It’s thought that there’s no cure for such diseases, so all you can do is try to stay in remission for as long as possible between attacks. But can a plant-based diet help to both prevent and treat these debilitating conditions? This is a complex topic, so it has been covered in three parts. This is part 3 of 5.

(See Further Notes, below, for a more detailed explanation of IBD, UC & CD)

This article will look at:

- Exclusion diets and IBD

- Fasting & CD

- Low-residue Diet and IBD (CD)

- Novel Anti-Inflammatory Diet Therapies and IBD (IBD-AID)

- Fibre Supplement Diets and IBD (UC & CD)

- a. Oat Bran

- b. Wheat Bran

- c. Psyllium

- d. Germinated Barley Boodstuff

- The Specific Carbohydrate Diet™ and IBD

- The Paleo Diet and IBD

- Modulen™ IBD and CD

- The Mediterranean Diet (MedD) & CD

- Historical Diets vs Modern Diets & IBD

- Global Incidence of IBD

Blog Contents

Exclusion Diets & IBD

Dr John McDougall states1 that “…considerable evidence indicates that introducing certain foods (including cow’s milk) too soon into an infant’s diet, at the time when its intestinal tract and immune systems are still immature, may provoke responses in its tissues that will lead to symptoms of allergy later in life…The ultimate and best test for identifying the substance suspected of causing an allergy is to eliminate the substance (whether it is a food, or a pollen, or a chemical compound), and then to note if the symptoms disappear and the patient’s health is improved. Confirmation of the diagnosis is made by adding the offending substance back to the patient’s diet or environment and observing if the illness returns. Don’t overlook the obvious truth that elimination of the villainous allergen is also the ultimate- and only-treatment for “curing” the allergy…

…Although countless substances can cause allergies, the foods he eats should be the first suspects that an allergic person should investigate. This is true for two reasons. First, whatever we eat is 100 percent within our control. Therefore, once the cause of a food allergy is identified, you can decide to remove that item from your diet. Second, suspecting your food is a good bet: foods represent one of our most frequent, intimate, and diversified contacts with our environment. Molecule for molecule, we interact with the components in our foods more than with air or water, and, obviously, the complexity of the substances we contact through our foods is many times greater than is that of compounds found in air or water.”

He goes on to advise sufferers of allergies of any sort to “[e]liminate entirely, or reduce significantly, the allergens in your environment, whether in air, or drinks, or foods. Most people will resolve their food allergies by simply adopting a starch-based diet as taught in the McDougall Program, for the simple reason that five of the leading causes of food allergies are eliminated immediately when this change is made: Gone are the dairy products, eggs, chocolate, nuts, shellfish, and fish. If your problems persist, then the next suspects to eliminate are wheat, corn, citrus fruits, tomatoes, and strawberries – the most frequent causes of allergy among the foods in the vegetable kingdom.”

A 19932 exclusion study found that “Food intolerances discovered were predominantly to cereals, dairy products, and yeast. Diet provides a further therapeutic strategy in active Crohn‘s disease.”

For decades, physicians based dietary counseling for IBD patients on restrictive criteria. This was because the so-called “bowel rest” was considered as a sine qua non to induce disease remission. However, controlled trials clearly demonstrated that drug-induced IBD remission was not influenced by the type of nutritional support (i.e., enteral, parenteral or oral conventional foods)3 4 5 Thus, the concept of “bowel rest” has been abandoned, and IBD patients are now advised to eat a diet as unrestricted as possible.6

Fasting & CD

When CD sufferers fast, their symptoms appear to get better.7 There are conflicting views on this method of dealing with CD and it is vital that your doctor is consulted before considering intermittent, 5:2, or long-term fasting. This is partly because some CD sufferers are already underweight because of poor nutrient absorption and/or elective reduction of caloric intake because of the adverse symptoms of their condition when consuming food.8 9 10 11

A renowned expert on water fasting, Dr Michael Klaper, talks in the following radio interview12 about how fasting can improve health, including for those with IBD and related diseases:

In a documented interview13 with the IMCJ, Dr Alan Goldhamer, another internationally-respected expert in fasting, discusses the benefits of this method in dealing with inflammatory disease and diseases of dietary excess. In the following video14 “Prolonged Water Fasting Q&A Dr. Alan Goldhamer”, Dr Goldhamer goes into more detail on why fasting works, dealing with its positive influence on microbiota, hypertension and other chronic diseases.

Low Residue Diet and IBD (CD)

A low-residue diet was often recommended for the management of an acute flare up of IBD, especially in patients with intestinal strictures or narrowing. Although the low-residue diet can be prescribed for short-term use, in clinical practice, patients often followed the diet long-term. The primary purpose of a low residue diet is to reduce the frequency and volume of stools and reduce the risk for intestinal obstruction, usually in preparation for colonoscopy, so that nothing obstructs the camera’s internal view.

A 2015 study 15 concluded that: “…there is insufficient evidence to further justify the clinical use of a low-residue diet. On the basis of this literature review, we suggest redefining a low-residue diet as a low-fiber diet and to quantitatively define a low-fiber diet as a diet with a maximum of 10 g fiber/d. A low-fiber diet can be applied in both diagnostic and therapeutic situations. Diagnostically, a low-fiber diet is used in the preparation for a colonoscopy. Therapeutically, a low-fiber diet is part of the treatment in acute relapses of IBS, inflammatory bowel diseases, or diverticulitis. Upon achieving remission, the amount of fiber should be systematically increased until achieving the recommended amount of fiber in a healthy diet.”

In the literature, there have been discrepancies as to the actual composition/definition of low-residue and low-fibre diets. A low-residue diet requires the elimination of whole grains, legumes and all fruits and vegetables (except for bananas and skinless potatoes), dairy and fibrous meats.16 This is not the same as a low-fibre diet which excludes only insoluble fibre.

A 1985 prospective study17 in subjects with active CD compared a low-residue diet to an unrestricted diet. It found no differences in outcome including symptoms, need for hospitalisation, need for surgery, new complications, nutritional status, or postoperative recurrence.

Due to lack of evidence, there appears to be no reason to restrict residue from the diet, however anecdotally CD patients with obstructive symptoms and strictures report improvement in symptoms when following a diet reduced in fibre (total daily fibre intake < 10 g) 15 18

The side-effect of reducing residue/fibre in the colon is that there is then little or no “food” for the gut bacteria – and this should be a great cause of concern if maintained for a medium- to long-period of time. We saw the importance of gut microflora (microbiota) in part 2.

A small pilot study 19 in CD reported a marked decrease in microbial diversity with a low-residue diet. This is concerning considering that low diversity of the microbiota has been linked to a variety of chronic diseases. 20 Furthermore, improvements in inflammatory markers have not been demonstrated with a low-residue diet in CD. 21

As in the vast majority of these matters, more research is required; however, it is clear at this stage that a low-residue diet could potentially have negative consequences on IBD, and, therefore, prolonged avoidance of fibre is to be discouraged. 22

Novel Anti-Inflammatory Diet Therapies and IBD (IBD-AID)

While the exact aetiology of IBD remains unclear, increasing evidence suggests that the gastrointestinal microbiome plays a critical role in disease pathogenesis (the manner in which a disease develops). This was mentioned above and supported by evidence in part 2. In addition, a 2006 study concluded that: “…tissue-associated flora of UC patients is broadly similar to that of healthy individuals and significantly different from that of CD patients [and so] may indicate that, beyond its obvious role in fuelling inflammation, the commensal [intimate and mutually-beneficial] flora has profoundly different roles in the aetiologies of these diseases. Furthermore, since the differences in microflora between CD and UC patients appear relatively large and well-defined, this study should be followed by quantitative phylum level assessment in tissue-associated and fecal microbiotas of a large group of patients to establish their generality in multiple ethnic backgrounds and nutritional regimens. These differences could be used to diagnose cases of indeterminate colitis and perhaps even identify people with potential CD susceptibility before they become symptomatic, as well as to enable the design of future means of prevention.” 23

A 2004 study 24 concluded that: “Mucosal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease is associated with loss of normal anaerobic bacteria.”

The fact that over 99% of the trillions of gut bacteria are anaerobic (that is, they exist in oxygen-free conditions) means that it has only recently become possible to study them with new methods. This is explained in a 2014 publication: 25 “Studies on strictly anaerobic microorganisms represent one of the most challenging areas of research, because anaerobic conditions (oxygen-free) need to be reconstructed to understand microbial activities and to obtain enrichments and pure culture…Microbial community studies using 16S rRNA gene, as well as various functional genes, have offered new insights into anaerobic microbial ecology. Furthermore, numerous new lines of evidence offered by recent omics-driven and high-throughput sequencing studies provide a new vision of the anaerobic microbial world.”

Manipulation of the gastrointestinal microbiome through diet interventions, in attempt to reduce systemic inflammation, is increasingly recommended as adjuncts to ongoing medical therapy. The Anti-Inflammatory Diet (IBD-AID) is a nutritional approach designed to address nutrient adequacy, malabsorption and symptoms [45].

A 2014 study 26 emphasised: “…the importance of dietary manipulation as an adjunct to the limited existing management options for IBD…” And that the study of the IBD-AID: “…would benefit from the rigorous analysis provided by a randomized clinical trial, with evaluation of mucosal healing and assessment of change in gut flora to examine the exact mechanism(s) of benefit.” More research is, of course, needed in order to persuade doctors to look further than the poorly-performing current methods.

Indeed, the latter study considered that: “Physicians are not provided with specific dietary treatments to offer their IBD patients27 , and recommendations for normal diet are often based upon a philosophy of ‘if it hurts, don’t do it’.”

IBD-AID restricts the intake of particular carbohydrates (lactose, refined and processed complex carbohydrates), includes the ingestion of pre- and probiotic foods, and modifies dietary fatty acid intake specifically decreasing the total fat, saturated fats, the elimination of hydrogenated oils, and encouraging the increased intake of foods rich in n-3 PUFA (omega-3).

Fibre Supplement Diets and IBD (UC & CD)

The use of fibre in IBD treatments are more commonly seen for the use of supplements rather than diet interventions and for the management of UC and CD rather than its prevention or the permanent elimination of symptoms. A 2014 study 28 considered that, while mainstream practitioners generally still consider that they are not presented with sufficient clear and definitive research results, interventions with the use of fibre do appear to have the potential to relieve symptoms and/or to maintain disease remission in IBD patients. The type of fibre may be an important consideration, of course. The researchers went on to say: “The potential anti-inflammatory role of fiber is intriguing and merits further investigation in adequately powered clinical trials. Excluding overt gastrointestinal obstruction, there was no evidence that fiber intake should be restricted in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.”

It is a surprise to me that there is so little understanding of the vital role played by fibre. Indeed, it was quite revealing of how cutting-edge research is in terms of the benefits of fibre when one looks at the Wikipedia search29 for “List of macronutrients”, the following is what appears:

a. Oat Bran and UC

A controlled intervention study 30 adding 60 grams/day of oat bran (equivalent to 20 grams oat fibre/day) to the diet of subjects with quiescent (in a state or period of inactivity or dormancy) UC reported no signs or symptoms of UC relapse after 12 weeks. A subgroup of subjects noted a decrease in abdominal pain, reflux and diarrhoea. The greatest impact of the oat bran intervention was seen on the faecal short chain fatty acid (SCFA – including acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, valeric acid, and isovaleric acid) concentrations found in the stool. Fifteen subjects demonstrated a 36% increase in faecal butyrate concentrations within four weeks of intervention which was maintained throughout the 12-week intervention. This finding is important as increasing evidence suggests SCFA’s play an essential role in maintaining the health of colonic mucosa as butyrate is the main energy substrate for colonocytes (epithelial cells of the colon.)31

Butyrate also plays an important role in the prevention and treatment of distal UC – left-sided (distal) colitis is a form of UC that begins at the rectum and extends up to the left colon. 32 The researchers conclude that: “The supplementation with oat bran in this population warrants further investigation with a larger sample size, over a longer-term to determine the overall benefit as a maintenance therapy for UC.”

b. Wheat Bran and CD

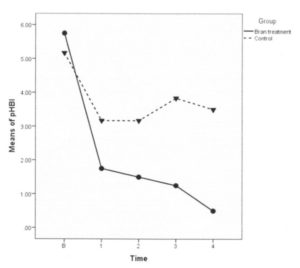

A randomised control trial 33 in CD where subjects were instructed to consume a high fibre diet, including consumption of whole wheat bran cereal (1/2 cup daily) and restrict refined carbohydrates, reported improved health-related quality of life as measured by the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) 34 . Significant improvements were seen in the clinical disease activity scores, as measured by partial Harvey-Bradshaw index (pHBI) – see chart below. A much larger sample size, over a longer term, including subjects receiving a variety of medications, is needed to verify the results of this study.

The above pHBI Graph measures CD symptoms (general well-being, abdominal pain, and liquid stools). This graph shows the results of the above study, namely that the high fibre (bran) treatment group and the control group mean scores were close at baseline. Mean scores for both groups dropped during the first week, the intervention group dropping more steeply. From week 1 until the end of the study, the control group means did not drop further and in fact increased slightly. All participants in the high fibre group scored a ‘zero’ on the pHBI at week 4.

c. Psyllium and UC

Taking psyllium (also known by the trade name Metamucil) is not something that I would recommend. Eating prunes (dried plums) has been shown to be much more effective. 35 36 37 38 39 40 Watch this video 41 by Dr Michael Greger for further details on the latter research.

A randomised control trial 42 in subjects with UC in remission comparing psyllium fibre versus mesalamine (a 5-aminosalicylic acid which is an aminosalicylate anti-inflammatory drug used to treat IBD) versus psyllium fibre plus mesalamine reported continued remission at 12 months and slightly lower relapse rates in the mesalamine plus psyllium fibre group. Probability of continued remission was similar between all three groups.

A 1991 randomised control trial43 with UC in remission over four months found psyllium to be superior to placebo in relieving gastrointestinal symptoms , especially for diarrhoea and constipation.

A 2017 report44 states that only: “…weak evidence suggests that psyllium fibre may be efficacious in maintaining remission in UC. So, as stated above, my personal suggestion is to follow what Gr Greger suggests – eat real wholefood!

d. Germinated Barley Foodstuff and UC

Germinated barley foodstuff is an insoluble dietary fibre made by milling and sieving brewer’s spent grain 45 . Germinated barley foodstuff has prebiotic [a.] properties, containing glutamine-rich protein and hemicellulose-rich [b.] fibre which has been shown to reduce clinical activity and prolong remission in UC.

An open-label trial 46 with UC in remission received 30 grams (three times daily) of germinated barley foodstuff in addition to conventional medication for two months. A statistically significant reduction in mean CRP [c.] was seen in the germinated barley foodstuff intervention group, as well as a significant reduction in abdominal pain and cramping. The researchers concluded that: “…the consumption of GBF [germinated barley foodstuff ] along with routine medication…attenuates the inflammation and appears to be an effective and safe treatment in UC.” They continued to say that; “…it can prolong the remission course with an improvement in clinical signs.”

[a.] Prebiotic food ingredients induce the growth or activity of beneficial microorganisms which can alter the composition of organisms in the gut microbiome).

[b.] Hemicellulose is any of a class of substances which occur as constituents of the cell walls of plants and are polysaccharides of simpler structure than cellulose.

[c.] CRP (C-reactive protein) is a substance produced by the liver in response to inflammation. A high level of CRP in the blood is a marker of inflammation.

A similar designed study46 found that 20 grams of germinated barley foodstuff reduced levels of TNF-α [d.], IL-6 [e.] and IL-8 [f.], with significant reductions in IL-6 nd IL-8. Length of remission has also been prolonged with long-term administration (12 months) of 20 grams of germinated barley foodstuff [58]. Germinated barley foodstuff appears to be a safe and effective maintenance therapy to prolong remission in patients with UC.

[d.] TNF-α (Tumour necrosis factor) is a cell signalling protein involved in systemic inflammation.

[e.] IL-6 (Interleukin 6) is interleukin (any of a class of glycoproteins produced by leucocytes for regulating immune responses) that acts as both a pro-inflammatory cytokine (cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins that are important in cell signalling). and an anti-inflammatory myokine. (a type of cytokine).

[f.] IL-8 (Interleukin 8) is a chemokine (a small cytokine, or signalling protein ) produced by macrophages (mobile white blood cells) and other cell types such as epithelial cells (one of the four types of cells from which animal tissues are constructed – epithelial, nervous, muscle, and connective), airway smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells (specialised epithelial cells lining blood vessels.). Endothelial cells store IL-8 in their storage vesicles.

The Specific Carbohydrate Diet™ (SCD) and IBD

I do not recommend this diet, partly because of its inclusion of many foods that a WFPB diet would avoid. However, I have included it because there is some research showing positive effects in relation to IBD (UC & CR).

The SCD diet is one of the most popular diets in the lay literature used by patients with IBD, even though there is a lack of evidence-based published data on this diet. To date, what evidence exists is based on retrospective surveys and case reports. Based on the book “Breaking the Viscous Cycle” by Elaine Gloria Gottschall, this diet is a strict grain free, sugar-free and complex carbohydrate-free diet regimen. There is a list 47 of permitted and non-permitted foods which are referred to as “Legal/Illegal” foods. The author explains that: “The allowed carbohydrates are monosaccharides and have a single molecule structure [fructose, glucose, galactose] that allow them to be easily absorbed by the intestine wall. Complex carbohydrates which are disaccharides (double molecules) [e.g. sucrose, lactose and maltose] and polysaccharides (chain molecules) [e.g. starch, glycogen, cellulose] are not allowed. Complex carbohydrates that are not easily digested feed harmful bacteria in our intestines causing them to overgrow producing by products and inflaming the intestine wall. The diet works by starving out these bacteria and restoring the balance of bacteria in our gut.”

My personal opinion is that both this diet and the above underlined parts of the author’s statement do not fit in with reliable research findings. This becomes even more apparent when one looks at the sorts of foods that are encouraged (“legal”) in this diet: “Staples of the diet then become fresh or frozen meats, certain cheeses and yogurts, eggs and some fruits and vegetables, making it paleo-esque in many ways.” 48 A WFPB diet addresses the needs of the body as an infinitely complex, dynamic and interrelated whole. Any dietary intervention which introduces foods that may improve a limited number of health factors (e.g. reduced diarrhoea, blood pressure, blood sugar levels etc) should both increase factors which improve overall health and decrease factors which damage overall health. An dietary intervention should not introduce foods that have been clinically proven to cause harm, such as animal protein and animal fat.49

Some research and surveys50 51 52 53 54 have produced positive results. But, as is usual in these cases of commercially-motivated/derived dietary “cure alls”, one needs to look carefully at the research methods – in particular, the nature of the control groups against which the control group was compared. As one review study 55 stated in conclusion regarding SCD: “Rigorous prospective, RCTs [randomised control trials] in pediatrics and adults are needed to determine the merits of this diet for management of IBD.”

The Paleo Diet and IBD

The paleo (or Palaeolithic) diet56 is another popular diet amongst patients with IBD. It recommends avoidance of processed food, refined sugars, legumes, dairy, grains and cereals, and instead it advocates for grass-fed meat, wild fish, fruit, vegetables, nuts and “healthy” saturated fat. While it makes sense that a diet that promotes avoidance of refined and extra sugars and processed energy dense food would have health effects, I have not found any peer-reviewed clinical trials that have examined the efficacy of this diet for IBD. The only source57 I could find that advocates the paleo diet for CD appears to have link that do not work and bases its hypothesis on one undocumented case study.

Dr Greger has clear views 58 on the paleo diet:

- “It might be reasonable to assume our nutritional requirements were established in the past, but why the Paleolithic period? Why only the last two million years of human evolution? We have been evolving for about 20 million years since we split off from our last common great ape ancestor, during which time our nutrient requirements and digestive physiology were relatively set and likely little affected by our hunter-gatherer days at the tail end. So what were we eating for the first 90 percent of our time on Earth? What the rest of the Great Apes were eating: more than 95 percent plants. Indeed, for the vast majority of our evolution, it appears we, like our Great Ape cousins, ate primarily leaves, stems, and shoots (in other words, vegetables), and fruit, seeds, and nuts.

- In modern times, populations where many of our deadliest diseases were practically unknown, such as rural China and rural Africa, were reportedly eating huge amounts of whole plant foods, up to 100 grams of fiber every day, which is what researchers have estimated our Paleolithic ancestors were getting…today in the United States, we tend to get fewer than 20 grams of daily fiber, which is about half the minimum recommended intake and only one-fifth the amount of rural Chinese and Africans, and our Paleolithic ancestors.

- Advocates of the Paleo diet are certainly right in railing against the consumption of dairy and refined, processed junk, as well as encouraging high fruit, nut, and vegetable intake, but do they fail in promoting excess meat-eating, particularly products that bear little resemblance to the flesh of prehistoric wild animals? A review published in Meat Science [ 59 ] , for example, catalogued the laundry list of contaminants, including arsenic, mercury, lead, cadmium, and veterinary drugs such as antibiotic residues.

- There have been some studies published in the last two decades that have shown health benefits of Paleo-type diets [I will soon be publishing a blog specifically dealing with the paleo diet and exercise], but questions have been raised regarding their methodology. For example, some were conducted without a control group, for an extremely short duration, with very few participants, or on pigs instead of humans.“

Modulen™ IBD and CD

Modulen60 is a milk (casein) drink with chemicals and fragments of macronutrients added. Just to give you an idea of this, here is a list of the ingredients of Modulen IBD:

- glucose syrup

- casein (milk)

- sucrose

- milk fat

- medium chain triglycerides

- minerals

- potassium citrate

- calcium phosphate

- sodium citrate

- calcium carbonate

- magnesium chloride

- potassium hydroxide

- potassium chloride

- ferrous sulphate

- zinc sulphate

- magnesium oxide

- manganese sulphate

- copper sulphate

- sodium molybdate

- potassium iodide

- chromium chloride

- sodium selenate

- corn oil

- emulsifier:soy lecithin

- vitamins

- C

- E

- niacin

- pantothenic acid

- B6

- B1

- A

- B2

- folic acid

- K

- biotin

- D

- B12

- choline bitartrate

Regarding supplements in general (and the above liquid is basically baby calf growth fluid 61 62 with masses of “essential” supplements added) Dr John McDougall makes his position very clear:

“Nature’s foods are complete. To make a profit, manufacturers isolate out and concentrate nutrients, like vitamins and minerals, and sell them as expensive pills. The consequence is to create serious imbalances within the workings of your cells, and then diseases follow (including cancer, heart disease, and earlier death). Don’t risk your life and waste your money on these gimmicks. The only supplement I routinely recommend is vitamin B12.” 63

Dr T Colin Campbell 64 considers that:

“Consuming either animal based foods or vitamin supplements is not necessary to achieve ‘vitamin’ health. At best, they can only fill some gaps, when we choose not to do the right thing.”

Dr Michael Greger says65 :

“Generally speaking, Mother Nature’s powers cannot be stuffed into a pill.”

Dr Caldwell B Esselstyn says 66 :

“If eating copious amounts of leafy green vegetables, a multi vitamin is unnecessary.”

Naturally, supplementation is a method that makes sense if “proper” food is not being consumed at all (as in the Modulen IBD diet), but to make the assumption that individuals with IBD (UC or CD) should consider using this casein-based drink in place of trying a balanced WFPB diet is, in my opinion, questionable at the very least. For those who for medical reasons either cannot or have been advised should not consume any solid food, it is clear that supplementation in some liquid form would be necessary. At this stage, I have not come across research comparing fortified liquid drinks such as Modulen with smoothies/drinks made with whole foods. This would be an interesting area of research to follow.

Nestlé have successfully marketed Modulen to countless medical service providers and it is gaining ground as an alternative to steroidal treatment for children >5 and some adults. There is plenty on the Nestlé website that extols its benefits but, when compared with “real food” and when the negatives of cow’s milk are taken into consideration, I would not personally recommend this product unless I was to see more compelling research data which would have to satisfy two criteria:

- negate the plethora of research that vilifies cow’s milk, and

- demonstrate that this form of supplementation of fragmented foods elements is more effective than plant-based alternatives in achieving optimal health in humans.

The Mediterranean Diet (MedD) & CD

Whilst the MedD is not ideal, since it is not a non-SOS WFPB diet, evidence67 suggests that its increased emphasis on fresh fruits and veg, nuts and seeds and reduced animal and processed food intake (as compared with the SAD – Standard American Diet) results in a reduced incidence of IBD, including CD and UC.

Research in 2014 confirms that elements of the the MedD are associated with significant improvements in health status in general, with the researchers concluding that “High adherence to a MD [MedD] is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of overall cancer mortality (10%), colorectal cancer (14%), prostate cancer (4%) and aerodigestive cancer (56%).” 68 . Since colorectal cancer is strongly associated with UC, it makes sense that elements of the MedD will also be good for preventing UC which, in turn, may prevent the development of cancer.

In 2015, the latter research was updated, with the researchers concluding that “…the present update of our systematic review and meta-analyses provided additional important evidence for a beneficial effect of high adherence to MedD with respect to primary prevention overall cancer risk and specific types of cancer, especially colorectal cancer. These observed beneficial effects are mainly driven by higher intakes of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. [Notice that no mention is made of the often- (and mistakenly-) heralded benefits of olive oil.] Moreover, we report for the first time a small decrease in breast cancer risk (6%) with the pooling seven cohort studies. To further elucidate the relationship between Mediterranean dietary patterns and cancer types, future studies should adopt a precise definition of a MedD.”69

A precise definition of the MedD is something that’s worth establishing when deciding whether benefits are actually to be found in the current 21st Century versions . Having spent some time living next to the Mediterranean, I can vouchsafe that the once-relatively healthy MedD (as it may have been in previous decades and centuries) is almost unrecognisable in the day-to-day diets of many individuals currently living in Mediterranean countries.

Historical Diets vs Modern Diets & IBD

Records show that many chronic conditions such as asthma, general allergies and IBD have increased in recent times. As one study reported55 after looking at previous research:70 “The diet of today is considerably different from the traditional diet of previous generations, when the prevalence of IBD was considerably lower. The Western diet pattern is dominated by increased consumption of refined sugar, omega-6 polyunsaturated fats and fast food, combined with a diet deficient in fruit, vegetables, and fibre.” They continue: “Much of today’s food supply has been processed, modified, stored and transported great distances, in contrast to the traditional diet, where food that was produced locally was consumed shortly after harvest. This shift to the Western diet pattern is hypothesized to increase pro-inflammatory cytokines [proteins involved in communication within the immune system], modulate intestinal permeability, and alter the intestinal microbiota promoting a low-grade chronic inflammation in the gut.”71

The authors concluded that: “…encouraging intake of more anti-inflammatory dietary factors, such as plant-based foods rich in fibre and phytochemicals, and reducing intake of pro-inflammatory factors, such as fried or processed foods rich in trans-fatty acids, could be a potential strategy for reducing risk of UC [in particular, but this also applies to other IBD’s such as CD]. ..Overall, this suggests that the Western diet pattern is a risk factor for IBD.”

A 2010 study 72 made it clear that childhood cases of IBD were rising at an alarming rate.

There are several large scale studies that have attempted to elucidate the dietary components that are associated with IBD risk:

- A review of the relevant literature.73 Researchers concluded that: “High dietary intakes of total fats, PUFAs, omega-6 fatty acids, and meat were associated with an increased risk of CD and UC. High fiber and fruit intakes were associated with decreased CD risk, and high vegetable intake was associated with decreased UC risk.”

- A study of dietary fibre intake.74 . Researchers concluded that: “Based on data from the Nurses’ Health Study, long-term intake of dietary fiber, particularly from fruit, is associated with lower risk of CD but not UC. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanisms that mediate this association.“

- A study on dietary intake of linoleic acid (Omega 6).75 Researchers concluded that: “The data support a role for dietary linoleic acid in the aetiology of ulcerative colitis. An estimated 30% of cases could be attributed to having dietary intakes higher than the lowest quartile of linoleic acid intake.” Foods high in omega-6 include: vegetable oils, salad dressings, crisps and chips, fried fast food, cookies, pastries, crackers, pork, sausages, bacon, chicken, dairy, eggs, nuts. The researchers explain the reason why omega-6 is harmful: “Dietary linoleic acid, an n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, is metabolised to arachidonic acid, a component of colonocyte membranes. Metabolites of arachidonic acid have pro-inflammatory properties and are increased in the mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis.“

Global Incidence of IBD

IBD has traditionally been thought of as a disease of the Western hemisphere, however there is an increasing incidence in Japan, Hong Kong, Korea and Eastern Europe 76 77 . Although still rarer, an increasing incidence of IBD is also being identified in South Africa, South America and Saudi Arabia78 79 80 . The dramatic rise in incidence of IBD, particularly in South Asia, India and Japan, where traditionally there was a low incidence, suggests that environmental factors, such as the Western diet pattern, play an important role in disease pathogenesis81 82 83 . This hypothesis is further confirmed by the increasing incidence of the disease in immigrants to the Western hemisphere. Migration from a country with a history of low-incidence to a country of a higher incidence increases the risk of developing IBD, particularly in the first generation children84 . Diet composition has long been suspected to contribute to IBD. Thus, dietary patterns and nutrients are important environmental factors to consider in the aetiology of IBD73 85

Dr John McDougall points out86 that “Inflammatory bowel diseases occur almost exclusively in parts of the world where the diet is high in meat and dairy foods, and are rare in countries where people still consume starch based, almost entirely vegetarian meals. Severe “allergic-type” reactions to some of those rich foods have been suspected as being the causes of these conditions. Some clustering of cases in a family occurs, which is consistent with the fact that we learn our food preferences from our parents.”

Astonishingly, research back in 197587 showed that up to that year, only 18 cases of UC had ever been reported in the whole of the black populations of sub-Saharan Africa.

In part 4 of 5 we will look at the the Harvey-Bradshaw Index & CD, one of the tools used for monitoring CD symptomatic responses when selectively removing and then reintroducing sensitive foods to the diet.

Further Notes88 on Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD), Crohn’s Disease (CD) & Ulcerative Colitis (UC)

IBD refers to diseases of a chronic or remitting/relapsing intestinal inflammation. This guideline describes UC and CD as the major forms of inflammatory bowel diseases of unknown cause (aetiology). Both diseases develop complicated pathology, again with unknown causes, and mainly affect the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in various clinical symptoms.

UC and CD are collectively referred to as IBD because the two diseases share common or similar features; however, disease location, morphology (form and structure), and pathophysiology (physiological changes associated with a disease) are clearly different between them, and they are considered to be independent diseases. Moreover, it is necessary to classify them because diagnostic procedures, therapeutic interventions, and follow-up observation are somewhat different. Notably, it is called ‘IBD unclassified’ when colonic lesions have the features of IBD which cannot be classified as UC or CD.

Patients with IBD often experience impaired daily quality of life (QOL) since both diseases can appear at young ages and progress into repeated cycles of chronic relapse and remission throughout life.

UC is a diffuse non-specific inflammatory disease of unknown cause that continuously affects the colonic mucosa proximal from the rectum and often forms erosions and/or ulcers. It frequently repeats cycles of relapse and remission during its course and may be accompanied by extraintestinal complications. When it extensively affects the large intestine for a long period of time, a risk of developing cancer increases [a].

CD is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown cause, although there are theories: one theory suggests an abnormal immune response to gut bacteria; another suggests processed foods or recently emerged allergens may be responsible; additionally, there appears to be a genetic factor (gene NOD2) running in families.89 Other causal factors may include certain viral or bacterial infections, ethnicity, smoking and even the use of a treatment for acne scars (isotretinoin – although there are strong objections90 to this drug being responsible).

CD is characterised by discontinuously affected areas with transmural granulomatous inflammation (where intestinal walls are breached, resulting in an accumulation of immune cells called histiocytes – a type of tissue macrophage) and/or fistula (an abnormal connection between an organ and another structure). This is often referred to as a ‘leaky gut’, and as intestinal contents spill into the blood, and get attacked by white blood cells, the result may be all sorts of additional and serious health problems.

It can affect any region in the digestive tract from the mouth to the anus, but is more likely to involve the small intestine (the ileum) and large intestines (the colon and especially the ileocaecal valve) and the area around the anus (perianal region) [b]. The inflamed tissues become thick and swollen, and the inner surfaces of the digestive system may develop open sores (ulcers). Generally speaking it’s found in the colon some 30% of the time and 30% in the ileum/small intestine. Both sites have been shown, when taken together, to have an occurrence rate of approximately 40%.

CD is less common than UC. Both men and women are equally affected. CD can occur at any age but there may be peaks at 15 to 30 years old and between 50 and 70 years old. Even very young children can develop the disease. In fact, 20 per cent of CD patients are diagnosed before the age of 20. It has also been established that CD is more common among smokers. There are many more potential symptoms in CD than in many gastrointestinal diseases. Signs and symptoms tend to flare up multiple times throughout life.

The most common features of CD this condition are:

- Persistent diarrhoea

- Abdominal pain and cramping

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Anal problems

- Anaemia

- Fever

Some people with CD have blood in the stool from inflamed tissues in the intestine; over time, chronic bleeding can lead to a low number of red blood cells (anaemia). The inflammation in CD extends through the bowel wall leading to abscess formation or scarring and narrowing of the bowel known as stricture formation. In addition, it may develop extraintestinal complications in systemic organs such as the liver, joints, the skin, and the eyes. This makes CD a ‘multi-system’ or generalised disease.

In addition, symptoms will depend on the severity of the disease and which part of the bowel is affected.

Traditional nutritional opinion has been that there is no specific diet recommended for all patients with CD. Nutritionists and medical professionals have historically considered that general nutrition should concentrate on providing adequate macro- and micro-nutrients in an easily-absorbed form, especially after intestinal surgery. The object of management of the disease to date has been to treat periods of relapse in order to produce remission. The task then has been to maintain the disease in an inactive state. If complications develop they would then need to be treated specifically. The treatment of CD has always complex, difficult and has required specialist medical advice. Treatment has usually focused on a combination of dietary intervention and drugs. Because of the relative ineffectiveness of this approach, surgery has been required for the majority of patients.

The disease is named after Dr Burrill B Crohn, a New York doctor, who reported cases in the 1930’s.

The incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) is significantly increased in UC patients who have extensive lesions for a long period of time, and it is also known that the incidence of cancers in the small and large intestines, especially in the rectum and anal canal region, is high in CD patients. Therefore, an efficient surveillance strategy for cancer development is normally expected to be established by the patient’s doctor. IBD is considered to be a disease that does not significantly affects the patients’ life prognosis, although IBD patients have slightly shorter life prognosis compared to normal individuals.

This is a must-watch video ‘Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Crohns, and Colitis with Pamela A. Popper‘.

References

- Dr John McDougall: Allergic Reactions to Food. [↩]

- Riordan, A. Treatment of active Crohn’s disease by exclusion diet: East Anglian Multicenter Controlled trial. Lancet 342:1131, 1993 [↩]

- Del Pinto R., Pietropaoli D., Chandar A.K., Ferri C., Cominelli F. Association Between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Vitamin D Deficiency: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2708–2717. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000546. [↩]

- Meckel K., Li Y.C., Lim J., Kocherginsky M., Weber C., Almoghrabi A., Cohen R.D. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration is inversely associated with mucosal inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016;104:113–120. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.123786. [↩]

- Torki M., Gholamrezaei A., Mirbagher L., Danesh M., Kheiri S., Emami M.H. Vitamin D Deficiency Associated with Disease Activity in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015;60:3085–3091. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3727-4. [↩]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3413052/ [↩]

- Indian J Gastroenterol. 2008 Nov-Dec;27(6):239-41. Ramadan fasting and inflammatory bowel disease. Tavakkoli H1, Haghdani S, Emami MH, Adilipour H, Tavakkoli M, Tavakkoli M. [↩]

- Crohns Disease and Fasting.mov. [↩]

- Crohns Disease and fasting. [↩]

- Healing Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Through Natural Means. [↩]

- Cured Crohn with fasting. [↩]

- Dr. Michael Klaper: Water Fasting for Better Health – Episode 54 [↩]

- Integr Med (Encinitas). 2014 Jun; 13(3): 52–57. PMCID: PMC4684131. PMID: 26770100. Alan Goldhamer, dc: Water Fasting—The Clinical Effectiveness of Rebooting Your Body. Craig Gustafson [↩]

- Prolonged Water Fasting Q&A Dr. Alan Goldhamer [↩]

- Vanhauwaert E., Matthys C., Verdonck L., De Preter V. Low-Residue and Low-Fiber Diets in Gastrointestinal Disease Management. Adv. Nutr. 2015;6:820–827. doi: 10.3945/an.115.009688. [↩] [↩]

- Vanhauwaert E., Matthys C., Verdonck L., De Preter V. Low-Residue and Low-Fiber Diets in Gastrointestinal Disease Management. Adv. Nutr. 2015;6:820–827. doi: 10.3945/an.115.009688. [↩]

- Levenstein S., Prantera C., Luzi C., D’Ubaldi A. Low residue or normal diet in Crohn’s disease: A prospective controlled study in Italian patients. Gut. 1985;26:989–993. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.10.989. [↩]

- Nutrients. 2017 Mar; 9(3): 259. Published online 2017 Mar 10. doi: 10.3390/nu9030259. An Examination of Diet for the Maintenance of Remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Natasha Haskey and Deanna L. Gibson. [↩]

- Walters S.S., Quiros A., Rolston M., Grishina I., Li J., Fenton A., Nieves R. Analysis of Gut Microbiome and Diet Modification in Patients with Crohn ’ s Disease. SOJ Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014;2:1–13. doi: 10.15226/sojmid/2/3/00122. [↩]

- Zhang Y.-J., Li S., Gan R.-Y., Zhou T., Xu D.-P., Li H.-B. Impacts of gut bacteria on human health and diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:7493–7519. doi: 10.3390/ijms16047493. [↩]

- Bartel G., Weiss I., Turetschek K., Schima W., Puspok A., Waldhoer T., Gasche C. Ingested matter affects intestinal lesions in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008;14:374–382. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20295. [↩]

- Hwang C., Ross V., Mahadevan U. Popular exclusionary diets for inflammatory bowel disease: The search for a dietary culprit. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014;20:732–741. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000438427.48726.b0. [↩]

- Gophna U., Sommerfeld K., Gophna S., Doolittle W.F., Van Zanten S.J.O. Differences between tissue-associated intestinal microfloras of patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:4136–4141. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01004-06. [↩]

- Ott S.J., Musfeldt M., Wenderoth D.F., Hampe J., Brant O., Fölsch U.R., Schreiber S. Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:685–693. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.025403. [↩]

- Microbes Environ. 2014 Dec; 29(4): 335–337. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME2904rh. PMCID: PMC4262355. PMID: 25743613. The Challenges of Studying the Anaerobic Microbial World. Koji Mori1, and Yoichi Kamagata [↩]

- Olendzki B.C., Silverstein T.D., Persuitte G.M., Ma Y., Baldwin K.R., Cave D. An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: A case series report. Nutr. J. 2014;13:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-5. [↩]

- Dig Dis Sci. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 May 1. Published in final edited form as: Dig Dis Sci. 2013 May; 58(5): 1322–1328. Published online 2012 Aug 26. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2373-3. PMCID: PMC3552110. Dietary Patterns and Self-Reported Associations of Diet with Symptoms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aaron B. Cohen, MD, Dale Lee, MD, Millie D. Long, MD, MPH, Michael D. Kappelman, MD, MPH, Christopher F. Martin, MSPH, Robert S. Sandler, MD, MPH, and James D. Lewis, MD, MSCE [↩]

- Wedlake L., Slack N., Andreyev H.J., Whelan K. Fiber in the treatment and maintenance of inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014;20:576–586. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000437984.92565.31. [↩]

- List of Macronutrients. Wikipedia. [↩]

- Hallert C., Bjorck I., Nyman M., Pousette A., Granno C., Svensson H. Increasing fecal butyrate in ulcerative colitis patients by diet: Controlled pilot study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2003;9:116–121. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200303000-00005. [↩]

- Roediger W.E. Utilization of nutrients by isolated epithelial cells of the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:424–429. [↩]

- Vernia P., Marcheggiano A., Caprilli R., Frieri G., Corrao G., Valpiani D., Torsoli A. Short-chain fatty acid topical treatment in distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995;9:309–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00386.x. [↩]

- Brotherton C.S., Taylor A.G., Bourguignon C., Anderson J.G. A high-fiber diet may improve bowel function and health-related quality of life in patients with Crohn disease. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2014;37:206–216. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000047. [↩]

- A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, Singer J, Williams N, Goodacre R, Tompkins C. Gastroenterology. 1989 Mar; 96(3):804-10. [↩]

- A. Attaluri, R. Donahoe, J. Valestin, K. Brown, S. S. C. Rao. Randomised clinical trial: Dried plums (prunes) vs. Psyllium for constipation. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011 33(7):822 – 828 [↩]

- V. Stanghellini, R. F. Cogliandro. Dried plums vs. psyllium. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011 33(10):1180 – 1 – author – reply – 1181 – 2 [↩]

- M. A. Sanjoaquin, P. N. Appleby, E. A. Spencer, T. J. Key. Nutrition and lifestyle in relation to bowel movement frequency: a cross sectional study of 20 630 men and women in EPIC-Oxford. Public Health Nutrition 2004 7(1):77-83 [↩]

- E. P. Halmos, P. R. Gibson. Dried plums, constipation and the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Aug;34(3):396-7; author reply 397-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04719.x. [↩]

- J. W. McRorie. Prunes vs. psyllium for chronic idiopathic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Jul;34(2):258-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04713.x. [↩]

- S. Lau, C. F. Donnellan, A. C. Ford. Do dried plums really help constipation? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Jun;33(11):1258-9; author reply 1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04649.x. [↩]

- “Prunes vs. Metamucil vs. Vegan Diet” by Dr Michael Greger [↩]

- Fernandez-Banares F., Hinojosa J., Sanchez-Lombrana J.L., Navarro E., Martinez-Salmeron J.F., Garcia-Puges A., Gine J.J. Randomized clinical trial of Plantago ovata seeds (dietary fiber) as compared with mesalamine in maintaining remission in ulcerative colitis. Spanish Group for the Study of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU) Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1999;94:427–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.872_a.x. [↩]

- Hallert C., Kaldma M., Petersson B.G. Ispaghula husk may relieve gastrointestinal symptoms in ulcerative colitis in remission. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1991;26:747–750. doi: 10.3109/00365529108998594. [↩]

- Nutrients. 2017 Mar; 9(3): 259. Published online 2017 Mar 10. doi: 10.3390/nu9030259. An Examination of Diet for the Maintenance of Remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Natasha Haskey and Deanna L. Gibson. [↩]

- Kanauchi O., Suga T., Tochihara M., Hibi T., Naganuma M., Homma T., Andoh A. Treatment of ulcerative colitis by feeding with germinated barley foodstuff: First report of a multicenter open control trial. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;37:67–72. doi: 10.1007/BF03326417. [↩]

- Faghfoori Z., Shakerhosseini R., Navai L., Somi M.H., Nikniaz Z., Abadi A. Effects of an Oral Supplementation of Germinated Barley Foodstuff on Serum CRP Level and Clinical Signs in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Health Promot. Perspect. 2014;4:116–121. [↩] [↩]

- Legal/Illegal List of Foods. Breaking The Vicious Cycle. [↩]

- USA News. What Is the Specific Carbohydrate Diet? by Anna Medaris Miller. [↩]

- The Problem With Protein. [↩]

- Suskind D.L., Wahbeh G., Cohen S.A., Damman C.J., Klein J., Braly K., Lee D. Patients Perceive Clinical Benefit with the Specific Carbohydrate Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016;61:3255–3260. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4307-y. [↩]

- Nieves R., Jackson R.T. Specific carbohydrate diet in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Tenn. Med. 2004;97:407. [↩]

- Kakodkar S., Farooqui A.J., Mikolaitis S.L., Mutlu E.A. The Specific Carbohydrate Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case Series. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015;115:1226–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.04.016. [↩]

- Obih C., Wahbeh G., Lee D., Braly K., Giefer M., Shaffer M.L., Suskind D.L. Specific carbohydrate diet for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice within an academic IBD center. Nutrition. 2015;32:418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.08.025. [↩]

- Burgis J.C., Nguyen K., Park K.T., Cox K. Response to strict and liberalized specific carbohydrate diet in pediatric Crohn’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22:2111–2117. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i6.2111. [↩]

- Nutrients. 2017 Mar; 9(3): 259. Published online 2017 Mar 10. doi: 10.3390/nu9030259. An Examination of Diet for the Maintenance of Remission in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Natasha Haskey and Deanna L. Gibson. [↩] [↩]

- The Paleo Diet. Loren Cordain. [↩]

- Crohn’s disease successfully treated with the paleolithic ketogenic diet. August 8 2016 by Dr. Andreas Eenfeldt, MD in Digestive issues, Paleo diets. [↩]

- Paleolithic Diets by Dr Michael Greger. [↩]

- United States Department of Agriculture Food Safety and Inspection Service Meat Science. [↩]

- Modulen IBD Ingredients and Datasheet [↩]

- Cow’s Milk – But It Looks So Innocent… [↩]

- Casein in Dairy = Cancer in Humans? [↩]

- Hot Topics: Supplements by Dr John McDougall [↩]

- Do You Need Vitamin Supplements? February 1, 1996. By T. Colin Campbell, PhD [↩]

- Supplements by Dr Michael Greger. [↩]

- Vitamins – What Vitamins should I take? By Dr Caldwell B Esselstyn. [↩]

- Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD). Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, Fear N, Price A, Carpenter L, van Blankenstein M Gut. 1996 Nov; 39(5):690-7. [↩]

- Schwingshackl L., Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;135:1884–1897. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28824. [↩]

- Schwingshackl L., Missbach B., König J., Hoffmann G. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:1292–1299. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014001542. [↩]

- Review The increase in the prevalence of asthma and allergy: food for thought. Devereux G. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006 Nov; 6(11):869-74. [↩]

- Review The role of diet in triggering human inflammatory disorders in the modern age. Huang EY, Devkota S, Moscoso D, Chang EB, Leone VA. Microbes Infect. 2013 Nov; 15(12):765-74. [↩]

- Malaty HM, Fan X, Opekun AR, Thibodeaux C, Ferry GD.Rising incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among children: a 12-year study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Jan;50(1):27-31 [↩]

- Hou J.K., Abraham B., El-Serag H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;106:563–573. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.44. [↩] [↩]

- Ananthakrishnan A.N., Khalili H., Konijeti G.G., Higuchi L.M., De Silva P., Korzenik J.R., Chan A.T. A prospective study of long-term intake of dietary fiber and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:970–977. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.050. [↩]

- Tjonneland A., Overvad K., Bergmann M.M., Nagel G., Linseisen J., Hallmans G., Palmqvist R., Sjodin H., Hagglund G., Berglund G., et al. Linoleic acid, a dietary n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and the aetiology of ulcerative colitis: A nested case-control study within a European prospective cohort study. Gut. 2009;58:1606–1611. [↩]

- Ng S.C., Tang W., Ching J.Y., Wong M., Chow C.M., Hui A.J., Li M.F. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn’s and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:158 e2–165 e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.007. [↩]

- Lovasz B.D., Golovics P.A., Vegh Z., Lakatos P.L. New trends in inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology and disease course in Eastern Europe. Dig. Liver Dis. 2013;45:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2012.08.020. [↩]

- Ukwenya A.Y., Ahmed A., Odigie V.I., Mohammed A. Inflammatory bowel disease in Nigerians: Still a rare diagnosis? Ann. Afr. Med. 2011;10:175–179. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.82067. [↩]

- Al-Mofarreh M.A., Al-Mofleh I.A. Emerging inflammatory bowel disease in saudi outpatients: A report of 693 cases. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2013;19:16–22. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.105915. [↩]

- Archampong T.N., Nkrumah K.N. Inflammatory bowel disease in Accra: What new trends. West Afr. J. Med. 2013;32:40–44. [↩]

- Ng S.C. Emerging leadership lecture: Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: Emergence of a “Western” disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;30:440–445. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12859. [↩]

- Holmboe-Ottesen G., Wandel M. Changes in dietary habits after migration and consequences for health: A focus on South Asians in Europe. Food Nutr. Res. 2012;56:1–13. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v56i0.18891. [↩]

- Pugazhendhi S., Sahu M.K., Subramanian V., Pulimood A., Ramakrishna B.S. Environmental factors associated with Crohn’s disease in India. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2011;30:264–269. doi: 10.1007/s12664-011-0145-1. [↩]

- Legaki E., Gazouli M. Influence of environmental factors in the development of inflammatory bowel diseases. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016;7:112–125. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i1.112. [↩]

- Lee D., Albenberg L., Compher C., Baldassano R., Piccoli D., Lewis J.D., Wu G.D. Diet in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1087–1106. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.007. [↩]

- Colitis (Severe), Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Ulcerative Colitis, Crohn’s Disease [↩]

- Segal, I. The rarity of ulcerative colitis in South African Blacks. Am J Gastroenterology 74:332, 1980 [↩]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5847182/ [↩]

- Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, et al: A frameshift mutation in NOD2 is associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature 2001;411:603-606. [↩]

- Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013 Nov; 9(11): 752–755. PMCID: PMC3995201. PMID: 24764796. Isotretinoin, Acne, and Crohn’s Disease: A Convergence of Bad Skin, Bad Science, and Bad Litigation Creates the Perfect Storm [↩]