We’ve already seen that inflammation and depression appear to be linked when we were looking at the relationship of our gut microbiota to depression and other comorbid conditions1 , but there’s additional and clear evidence that wherever you find depression in a person, you’ll also find inflammation, and probably the other way around, too.

It’s traditionally thought that depression resulted from monoamine neurotransmitter deficiency, causing low levels of the neurotransmitters serotonin and norephrinephrine in the brain. But new evidence is pointing towards inflammation as a major culprit. What’s interesting is what causes the inflammation in the first place. The following research studies suggest potential causal factors which can be linked, I believe, to both the “unnatural” stresses and dietary habits of our modern way of life.

What’s really encouraging is that both of the latter potential causes are environmental/lifestyle factors, and that means they are to some extent within our own power as individuals to address and control. We will now look at some research dealing with the potential mechanisms involved in the suggested relationship between depression and inflammation.

Blog Contents

Cytokines, stress, inflammation & depression

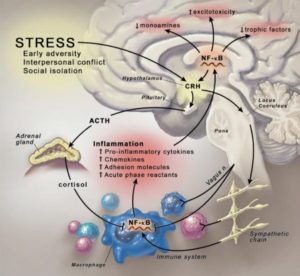

A 2009 study2 looked at the role of cytokines in major depression. When the body feels it is under threat, cytokines are innately released as urgent messengers, warning our immune system to be on alert for foreign invaders. The result of this can be varying levels of inflammation within the body and brain. Whilst the processes are rather complex, the following diagram (and key) provides an idea of the mechanisms involved.

Explanation of above diagram: Stress-induced activation of the inflammatory response. Psychosocial stressors activate central nervous system stress circuitry, including CRH and ultimately sympathetic nervous system outflow pathways via the locus coeruleus. Acting through alpha and beta adrenergic receptors, catecholamines released from sympathetic nerve endings can increase NF-κB DNA binding in relevant immune cell types, including macrophages, resulting in the release of inflammatory mediators that promote inflammation. Proinflammatory cytokines, in turn, can access the brain, induce inflammatory signaling pathways including NF-κB, and ultimately contribute to altered monoamine metabolism, increased excitotoxicity, and decreased production of relevant trophic factors. Cytokine-induced activation of CRH and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, in turn, leads to the release of cortisol, which along with efferent parasympathetic nervous system pathways (e.g., the vagus nerve) serve to inhibit NF-κB activation and decrease the inflammatory response. In the context of chronic stress and the influence of cytokines on glucocorticoid receptor function, activation of inflammatory pathways may become less sensitive to the inhibitory effects of cortisol, and the relative balance between the proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory actions of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, respectively, may play an increasingly important role in the neural regulation of inflammation. CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B.

Crossing the blood-brain barrier

The researchers report that patients with major depression have been found to exhibit increased peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers, including inflammatory cytokines. The latter have been shown to cross the blood-brain barrier and access the brain, interacting with virtually every aspect involved in depression, including:

- neurotransmitter metabolism

- neuroendocrine function

- neural plasticity

Characteristic features of depressive disorders

When these inflammatory pathways within the brain are activated, they appear to contribute to well-known factors that characterise depressive disorders, including:

- decreased neurotrophic support (relating to the growth of nervous tissue)

- oxidative stress (our brain contains millions of mitochondria which are vulnerable to attack from free radicals. Oxidative stress caused by out of control free radicals is now recognised as a major contributor to ageing and is thought to be the primary cause of all neurodegenerative disorders

- altered glutamate release/reuptake (glutamate is a powerful excitatory neurotransmitter that is released by nerve cells in the brain. It is responsible for sending signals between nerve cells, and under normal conditions it plays an important role in learning and memory)

- loss of glial elements (glia are dynamic elements of the nervous system, performing a variety of other essential functions. and can collectively be considered as supporting and protecting neurons in the healthy brain and also defending it in all forms of pathological insult)

The foregoing can all lead to excitotoxicity (the pathological process by which nerve cells are damaged or killed by excessive stimulation by neurotransmitters such as glutamate and similar substances).

Psychosocial stress & inflammation

Psychosocial stress is regarded as an established precipitant of mood disorders, being capable of stimulating inflammatory signalling molecules, for instance in factor kappa B (a transcription factor induced in many tissues by inflammation and immune responsiveness). It does this partly through activation of sympathetic nervous system (SNS) outflow pathways.

Resistance to treatment for depression linked to inflammation

Depressed patients who have increased inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), tend to have more resistance to traditional pharmacological treatments. However, there is some evidence that when antidepressants are effective, it may in part be because they are decreasing inflammatory responses to some extent – albeit that this may not have been considered as a targeted result when prescribing the particular antidepressant.

Conclusion

The researchers consider that: “…preliminary data from patients with inflammatory disorders, as well as medically healthy depressed patients, suggest that inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines or their signalling pathways may improve depressed mood and increase treatment response to conventional antidepressant medication.”

Cytokines in other studies

Other studies3 4 5 on the psychological effects of cytokines when they are administered to humans are very interesting. Symptoms of anxiety, irritability, and hyperarousal are also apparent following cytokine administration to humans (sometimes referred to as cytokine-induced depression). These symptoms were seen after acute administration of endotoxins (toxins present inside bacterial cells that are released when they disintegrate) as well as chronic treatment with interferon alpha (IFN-alpha). Multiferon is the trademark of a form of interferon used as a pharmaceutical drug. It’s composed of natural interferon alpha obtained from the leukocyte fraction of human blood following induction with Sendai virus.

Indeed, a 2005 study6 reported that hypomanic (a mild form of mania, marked by elation and hyperactivity) and even manic features, such as marked irritability, inability to sleep, and hyperactivity, were seen in a significant percentage of patients who were treated with IFN-alpha therapy.

Proinflammatory cytokines, gut microbiota and stress

A 2013 review7 looked at the mounting evidence for the involvement of inflammatory cytokines in the development of neuropsychiatric symptoms and depression.

Inflammation & stress in medical illness

They point out that during a medical – non-psychological – illness, inflammatory cytokines are elevated. [It would, therefore, explain why depression can so often accompany (be comorbid with) medical illnesses, since inflammation will be involved in both systems, physiological (fighting infections, etc) and psychological.] The reviewers state that cytokines are produced both centrally and systematically (partly within the gut and adipose tissue) following stress. [Medical illness would arguably produce a level of stress which, in turn, could accentuate the degree of inflammatory responses occurring with the individual.]

Microbiota, inflammatory cytokines and depression

The reviewers explain how the gut is a source of inflammatory cytokines and how gut microbiota influences our immune responses8 . Each person’s complex and dense community of gut microbiota may be influenced by genetic and environmental factors, and the balance between protective and harmful bacteria species may be important for general health9 .

The intestinal lining harbours immune cells, including dendritic cells and T cells10 11 , and may serve as a source of circulating cytokines.

Increased exposure to toxins, food allergens, and stress may promote a loss of protective microorganisms and increase inflammation in the gut, thus contributing to behavioural symptoms associated with increased inflammatory cytokines12 13 .

Gut microbiota of mice were manipulated and resulted in altered behaviour and hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) which indicated a potentially direct gut to brain connection that can influence behaviour14 .

The reviewers conclude by future research is need to “…determine whether drugs that target inflammatory molecules will be as efficacious as current antidepressant therapies, while remaining safe and well tolerated.” [Even though the composition of the gut microbiota is stated by the reviewers as being partly responsible for the production of cytokines (hence inflammation and thus depression), it is no great surprise that the solution of simply changing one’s diet and other lifestyle factors are sidelined in favour or the more profitable (copyrightable) pharmaceutical solution.]

Gut microbiota make-up has immunological importance

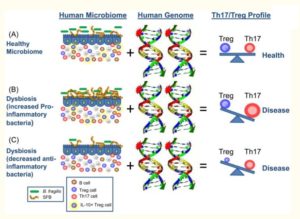

A 2010 review15 considered the role of the gut microbiota in the evolution of the adaptive human immune system. Whilst their focus is not primarily on the relationship between inflammation and depression, they do make some interesting remarks about the importance of the balance of bacteria in the gut: “Altered diets, widespread antibiotic use and other societal factors in developed countries may result in an unnatural shift in the community composition of a ‘healthy’ microbiota, leading to altered microbial colonization known as dysbiosis.” They include the following diagram showing the importance of the correct balance of tolerogenic (capable of producing immunological tolerance) and proinflammatory members within the microbiota. The key below explains the diagram in some detail.

Key to diagram: How the microbiome and the human genome contribute to inflammatory disease. In a simplified model, the community composition of the human microbiome helps to shape the balance between immuneregulatory (Treg) and pro-inflammatory (Th17) T cells. The molecules produced by a given microbiome network work with the molecules produced by the human genome to determine this equilibrium. (A) In a healthy microbiome, there is an optimal proportion of both pro- and anti-inflammatory organisms (represented here by SFBs and B. fragilis), which provide signals to the developing immune system (controlled by the host genome) that leads to a balance of Treg and Th17 cell activities. In this scenario, the host genome can contain ‘autoimmune specific’ mutations (represented by the stars), but disease does not develop. (B, C) The genome of patients with multiple sclerosis, type I diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease contain a spectrum of variants that are linked to disease by genome wide association studies (reviewed in (61)). Environmental influences, however, are risk factors in all of these diseases. Altered community composition of the microbiome due to lifestyle, known as dysbiosis, may represent this disease modifying component. An increase in pro-inflammatory microbes, for example SFBs in animal models, may promote Th17 cell activity to increase and thus predispose genetically susceptible people to Th17-mediated autoimmunity (B). Alternatively, a decrease or absence in anti-inflammatory microbes, for example B. fragilis in animal models, may lead to an under-development of Treg cell subsets (C). The imbalance between Th17 cells and Tregs ultimately leads to autoimmunity.

Inflammation, depression & the common cold

As far back as studies in 199616 , 199917 and 200018 it was confirmed that when your body is in an inflammatory state fighting off the common cold or flu, you can experience symptoms overlapping with depression— disrupted sleep, depressed mood, fatigue, foggy-headedness, and impaired concentration.

Depression as a psychoneuroimmunological dysfunction

A 2016 study19 looked at major depressive disorder (MDD) being due to psychoneuroimmunological dysfunction. As we have seen above, studies have already shown that there are increased levels of a variety of inflammatory mediators in people suffering from depression. This study supports the premise that increased inflammation does indeed play a role in depression; and, although it was only able to establish an association and not causation, it did confirm that there is a strong association of depression with high levels of inflammation as measured through CRP (C-reactive protein).

Some ways to reduce inflammation and, hopefully thereby, depression

An article in Psychology Today20 makes the observation that, when depression is viewed as a psychoneuroimmunological disorder, it helps to explain why reducing chronic inflammation in the body also improves and helps prevent depression.

The author lists five “scientifically proven ways” to help reduce inflammation:

- Reduce overall stress levels. “Even when things are hectic, find ways to take care of yourself and reduce stress. It’s not just good for your mind, but your body as well“

- Eat better: more anti-inflammatory foods, less inflammatory foods. Specifically, avoid those foods that worsen inflammation: “fried foods, soda, white bread and pastries, margarine, lard, and red meat…Foods that are anti-inflammatory include tomatoes, olive oil, green leafy vegetables, nuts like almonds, walnuts, fish, and berries.” [There is strong evidence that it is simply inaccurate to talk about olive oil21 and fish22 as being optimal foods to reduce inflammation.]

- Exercise: “...regular exercise 2-3 times a week…Aging is associated with increased inflammation, and many studies show that you can fight age-related inflammation with regular exercise, even light walking for 2-4 hours a week.” [Suggestions about the optimal amount of daily exercise differ. My opinion (which is in line with Dr Greger’s) is expressed elsewhere23 ]

- Mind-body exercises like yoga. “Yoga has been shown to boost natural antioxidants in the body that fight off inflammation.” [The benefits of mindfulness/meditation are looked at by one Dr Greger video24 and the benefits of meditation for the ageing process are discussed in another25 ]

- Breathing exercises for 10-20 minutes a day. “Simple calming breathing exercises both reduce stress and has an actual physical impact on your body. One study showed you can lower inflammatory markers in your body just after 20 minutes of yoga breathing.” [Seems pretty much linked to number 4]

High fat diets – microbiota, inflammation, depression & obesity

Taking up the above-mentioned relationship of inflammation and depression to diet, a 2017 review26 states that depression involves environmental, genetic and psychological factors, and one of the environmental factors mentioned is diet – specifically, the consumption of a high-fat diet.

Consumption of a high-fat diet leads to obesity (mentioned in a previous blog1 in more detail) and chronic systemic inflammation: “The gut microbiota mediates many effects of a high-fat diet on human physiology and may also influence the mood and behavior of the host.” The reviewers look in more detail at those recent studies that confirm the likely connection between obesity, gut microbiota and depression, paying particular attention to the mechanisms involved in a high-fat diet effects on chronic inflammation and brain physiology.

They conclude: “This body of research suggests that modulating the composition of the gut microbiota using prebiotics and probiotics may produce beneficial effects on anxiety and depression.” [As discussed elsewhere27 , there are concerns about the effectiveness and safety of probiotics. My research suggests that a whole food plant-based diet is the safest and most sensible means of providing all the pre- and probiotics that the vast majority of people need in order to maintain an optimally healthy gut.]

We are not alone in our bodies

A December 2017 review28 pointed out that the etiopathogenesis (the cause and subsequent development of an abnormal condition or of a disease) of psychiatric disorders is still not completely understood. However, they state that growing evidence supports the hypothesis that mental illness and related disturbances in brain neurobiology (the study of cells of the nervous system and the organisation of these cells into functional circuits that process information and mediate behaviour) do not necessarily originate in the brain. The suggestion that appears to be gaining ground is that inflammation plays a central role in psychiatric disorders, and in line the above-mentioned study, altered levels of peripheral cytokines, in particular, seem to have an important role.

Gut microbiota does appear to modulate low-grade inflammation, as well as high-order brain functions, including mood and behaviour. The microbiota is a large population comprising 40,000 bacterial species and 1,800 phila (a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class) involved in key processes important to maintain body homeostasis (the stable state of an organism and of its internal environment).

The reviewers conclude that: “Altered composition and functioning of gut microbiota have been reported in psychiatric disorders, and recent findings suggest that gut bacteria could be involved in modulating the efficacy of psychotropic medications [a chemical substance that changes brain function and results in alterations in perception, mood, consciousness or behaviour].”

A February 2018 study29 discusses the role of the microbiome and inflammation in liver disease. You may ask yourself what liver disease has to do with our discussion of inflammation and depression? Well, the authors of the study point out that both depression and inflammation are closely associated with liver disease.

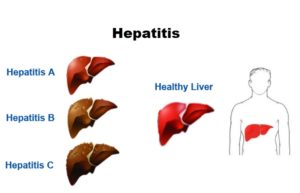

Hepatitis: Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver: Viruses cause most cases of hepatitis. The type of hepatitis is named for the virus that causes it; for example, hepatitis A, hepatitis B or hepatitis C. Drug or alcohol use can also cause hepatitis.

Hepatitis: Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver: Viruses cause most cases of hepatitis. The type of hepatitis is named for the virus that causes it; for example, hepatitis A, hepatitis B or hepatitis C. Drug or alcohol use can also cause hepatitis.

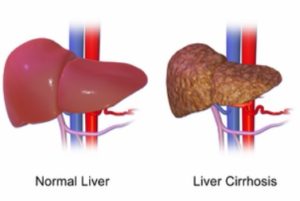

Liver cirrhosis: Liver cirrhosis is a condition where the liver doesn’t function properly due to long-term damage. This damage is typified by the replacement of normal liver tissue by scar tissue. It is most commonly caused by alcohol, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Liver cirrhosis: Liver cirrhosis is a condition where the liver doesn’t function properly due to long-term damage. This damage is typified by the replacement of normal liver tissue by scar tissue. It is most commonly caused by alcohol, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Every third patient with hepatitis or liver cirrhosis shows depressive symptoms. On the other hand, every third patient with depressive disorder develops an alcohol disorder at some point during his / her life.

They point out that a crucial link between hepatic disease and depression appears to be inflammatory processes where the microbiome and increased intestinal permeability of the intestine play a central role.

A few definitions before we continue:

- Metabolites: the intermediate end products of metabolism, which are usually small molecules

- Endotoxins: toxins present inside a bacterial cell that is released when it disintegrates

- Gram-negative bacteria: bacteria that don’t retain the crystal violet stain used in the gram-staining method of bacterial differentiation

- Cytokine cascade (also known as a cytokine storm): an autoimmune response in which the body’s immune system gets caught in a positive feedback loop leading to a runaway and potentially fatal autoimmune response

- Lipopolysaccharides (also known as lipoglycans and endotoxins): the major components of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria

Various elements disturb the delicate balance of the microbiota:

- depression

- liver disease

- alcohol consumption

- stress

- the ageing processes

These can all lead to increased intestinal permeability.

And the result of this is that bacteria and their metabolites (such as the endotoxin lipopolysaccharide) of Gram-negative bacteria can thus reach the blood circulation, resulting in inflammation in the liver and the brain via a cytokine cascade. This, in turn, can lead to liver changes, depression, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.

The reviewers conclude, therefore, that: “…liver values, blood glucose levels, and metabolic parameters should be closely monitored in patients with depressive disorders, and in the case of patients with hepatic diseases, increased attention should be given to depressive symptoms, diabetes and obesity.”

Joe’s comments

The above research clearly indicates that proinflammatory cytokines are linked to the symptoms of depression and anxiety. When these break through the intestine walls and get released into the bloodstream, they can cause significant, even fatal, damage. Perhaps the simplest and most sensible way to maintain healthy intestinal walls is through eating a non-inflammatory diet – and the best diet for this consists of unprocessed food plants in as close to their natural state as possible.

The links between depression, inflammation, stress and a variety of diseases (hepatic diseases and obesity are just two of those mentioned here) are pretty clear and convincing. We live in a period which is unique in the whole of human history. Never before have we been subjected the the unnatural and virtually continuous stresses imposed on us by our 24-hour, globally-connected society. Mobile phones, emails, TV, websites, books and magazines never stop calling on our attention. The results is that our bodies are primed for action like they would have been only very rarely throughout the vast majority of our history – for instance, when there was a genuine physical threat from an animal, another human or from some environmental event.

The flight or fight response is switched on all the time and this results in a low-grade inflammation that gradually – not immediately- but month by month, year by year causes chronic damage to our bodies. And the irony is that we are offered solutions to the stresses of our modern life – alcohol, “comfort” food, pharmaceuticals, surgical interventions – that then cause an exacerbation of the damage. And when the body finally breaks down, we are given more of the same solutions until we are so weakened that our poor bodies can no longer sustain us.

Depression, inflammation,disease – perhaps it’s overstating the already overstated, but a really healthy solution consists of eating the right foods, exercising regularly, getting plenty of sleep, and finding ways (such as mindfulness, yoga etc) to avoid as much stress as you possibly can.

References

- Gut Microbiota & Depression [↩] [↩]

- Biol Psychiatry. Biol Psychiatry. 2009 May 1; 65(9): 732–741. Published online 2009 Jan 15. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029. Inflammation and Its Discontents: The Role of Cytokines in the Pathophysiology of Major Depression. Andrew H. Miller, Vladimir Maletic, and Charles L. Raison. [↩]

- Capuron L, Gumnick JF, Musselman DL, Lawson DH, Reemsnyder A, Nemeroff CB, et al. Neurobehavioral effects of interferon-alpha in cancer patients: Phenomenology and paroxetine responsiveness of symptom dimensions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:643–652. [↩]

- Reichenberg A, Yirmiya R, Schuld A, Kraus T, Haack M, Morag A, et al. Cytokine-associated emotional and cognitive disturbances in humans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:445–452. [↩]

- Miller AH. Mechanisms of cytokine-induced behavioral changes: Psychoneuroimmunology at the translational interface. Brain Behav Immun. 2008 [↩]

- Constant A, Castera L, Dantzer R, Couzigou P, de Ledinghen V, Demotes-Mainard J, et al. Mood alterations during interferon-alfa therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C: Evidence for an overlap between manic/hypomanic and depressive symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1050–1057. [↩]

- Neuroscience. 2013 Aug 29; 246: 199–229. NIHMSID: NIHMS487915. Inflammatory Cytokines in Depression: Neurobiological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Jennifer C. Felger and Francis E. Lotrich [↩]

- Has the microbiota played a critical role in the evolution of the adaptive immune system? Lee YK, Mazmanian SK. Science. 2010 Dec 24; 330(6012):1768-73. [↩]

- Gut microbiota in health and disease. Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Physiol Rev. 2010 Jul; 90(3):859-904. [↩]

- Dendritic cells in intestinal immune regulation. Coombes JL, Powrie F. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008 Jun; 8(6):435-46. [↩]

- Adaptive immune regulation in the gut: T cell-dependent and T cell-independent IgA synthesis. Fagarasan S, Kawamoto S, Kanagawa O, Suzuki K. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010; 28():243-73.., 2010. [↩]

- Alterations in intestinal permeability. Arrieta MC, Bistritz L, Meddings JB. Gut. 2006 Oct; 55(10):1512-20. [↩]

- How stress induces intestinal hypersensitivity. Buret AG. Am J Pathol. 2006 Jan; 168(1):3-5. [↩]

- The intestinal microbiota affect central levels of brain-derived neurotropic factor and behavior in mice.

Bercik P, Denou E, Collins J, Jackson W, Lu J, Jury J, Deng Y, Blennerhassett P, Macri J, McCoy KD, Verdu EF, Collins SM Gastroenterology. 2011 Aug; 141(2):599-609, 609.e1-3. [↩] - Science. 2010 Dec 24; 330(6012): 1768–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1195568. PMCID: PMC3159383.

PMID: 21205662. Has the microbiota played a critical role in the evolution of the adaptive immune system? Yun Kyung Lee and Sarkis K. Mazmanian. [↩] - Hall S, Smith AP. Investigation of the effects and aftereffects of naturally occurring upper respiratory tract illnesses on mood and performance. Physiol Behav 1996;59: 569-577. [↩]

- Capuron L, Lamarque D, Dantzer R, Goodall G. Attentional and mnemonic deficit associated with infectious disease in humans. Psychol Med 1999;29: 291-297. [↩]

- Yirmiya R. Depression in Medical Illness: The Role of the Immune System. West J Med. 2000 Nov; 173(5): 333–336. [↩]

- Soledad Cepeda, M., Stang, P., & Makadia R. (2016) Depression Is Associated With High Levels of C-Reactive Protein and Low Levels of Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide: Results From the 2007-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Clin Psychiatry. 1666-71. [↩]

- New Research Shows Depression Linked with Inflammation Plus 5 Ways You Can Fight Inflammation. By Marlynn Wei M.D., J.D. Posted Jan 08, 2017. [↩]

- Olive Oil Injures Endothelial Cells [↩]

- Inflammation. Article by Dr Michael Greger. [↩]

- Physical Activity for Disease Prevention & Healthy Gut Microbiome [↩]

- How to Strengthen the Mind-Body Connection. Video by Dr Michael Greger. [↩]

- Does Meditation Affect Cellular Aging? Video by Dr Michael Greger. [↩]

- Effects of obesity on depression: A role for inflammation and the gut microbiota. Schachter J, Martel J, Lin CS, Chang CJ, Wu TR, Lu CC, Ko YF, Lai HC, Ojcius DM, Young JD. Brain Behav Immun. 2018 Mar;69:1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.08.026. Epub 2017 Sep 6. Review. PMID: 28888668. [↩]

- Study 5 – Do probiotic supplements affect microbiota and psychological symptoms? [↩]

- We are not alone in our body: insights into the involvement of microbiota in the etiopathogenesis and pharmacology of mental illness. Pisanu C, Squassina A. Curr Drug Metab. 2017 Dec 27. doi: 10.2174/1389200219666171227204144. PMID: 29283065. [↩]

- [Major depression and liver disease: the role of microbiome and inflammation]. Kahl KG, Krüger T, Eckermann G, Wedemeyer H. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2018 Feb 28. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123068. [Epub ahead of print] German. MID: 29490382. [↩]