It could be argued that the major nutritional problem experienced by those of us in ‘developed’ countries is an excess of macronutrients (particularly animal protein, saturated fat and sugar) plus salt. When this is combined, as it usually is, with a corresponding insufficient intake of micronutrients (minerals, vitamins, fibre and phytonutrients from fruit, veg, grains, legumes, nuts and seeds), then one descends the slippery slope towards truly unpleasant diseases and a likely early death.

Blog Contents

Fatty under-nutrition

Whilst the term ‘over-nutrition’ is often used to define this modern dietary dilemma, it should really be thought of as ‘under-nutrition’, being that it’s too low in nutrients and too high in calories – a sort of nutrient starvation as the body expands. This is an utterly new paradox, probably never seen on this planet prior to the last few human generations.

When FUN is no fun

For the sake of clarity, I’m going to term this condition ‘Fatty Under-Nutrition’, or FUN for short.

The FUN starts young

The FUN starts early in life – even before birth. When women become pregnant, they’re usually urged to eat more because they’re “eating for two”, even though expectant and lactating mothers only require an additional 300 or so calories each day 1 . What all pregnant women really should watch is that they eat a healthy and varied diet, sufficient in macronutrients, but which includes all the micronutrients they and their baby need – notably, omega-3 fatty acids (DHA, in particular), iron, calcium, choline, iodine, vitamins C, D, B9 and, especially in the case of pregnant women eating a WFPB/vegan diet, plus sufficient vitamin B12 2 . Of course, any supplementation should always be in consultation with the medical professional (OB or GP) who is overseeing the pregnancy.

Excessive FUN, that is, a diet low in micronutrients but high in macronutrients (especially animal protein, saturated fat and sugar) during pregnancy can have a range of effects on the health of the mother and baby. The most obvious is excessively rapid weight gain in the mother. However, this factor alone has been shown 3 4 to:

- increase the risk of labour induction

- increase the risk of caesarean section

- result in a higher birth weight

- cause other complications during pregnancy and delivery

And it’s not just the mother

When infants and children are overfed, they can develop unhealthy dietary habits which may last a lifetime – being apparent in both their waistline and in the number of visits they need to make to their doctor and to the hospital later in life. Both quantity and type of food eaten in childhood can lead to metabolic implications with lifelong consequences.

Since mothers and expectant mothers want to do the very best for their children, they can be susceptible to over-feeding themselves and their babies in spite of their most loving and caring intentions. As one study stated: “In general, women are especially receptive to advice about diet and lifestyle before and during a pregnancy. This should be exploited to improve the health of future generations” 5 . Of course, in order to achieve this, the quality of the advice needs to be of the highest order.

In 2004, the American Dietetic Association pointed out that: “…the number of children who are overweight has more than doubled among 2- to 5-year-old children and more than tripled among 6- to 11-year-old children, which has major health consequences. This increase in childhood overweight has broadened the focus of dietary guidance to address children’s over consumption of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods and beverages and physical activity patterns. Health promotion will help reduce diet-related risks of chronic degenerative diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer, obesity, and osteoporosis.” 6

A 2000 study stated that: “During early life and development the embryo, fetus and infant are relatively plastic in terms of metabolic function. The effect of any adverse environmental exposure is likely to be more marked than at later ages and the influence is more likely to exert a fundamental effect on the development of metabolic capacity” 7 . Whilst any baby, infant or young child faces health problems if they are significantly underweight, it’s increasingly understood that being overweight can be equally problematic – if not more so in some respects. 8 9 10

A 2005 review 11 concluded that: “Infants who are at the highest end of the distribution for weight or body mass index or who grow rapidly during infancy are at increased risk of subsequent obesity.

A 2006 study 12 showed that when a 4-month infant is fed more calories than recommended, it is a strong predictor of both increased weight gain before 2 years and increased risk of becoming obese in childhood and adulthood.

The take-home message of this is that parents and care-givers should choose foods that promote a healthy body weight and resist the temptation to ‘spoil’ with food or aim to promote the rapid growth of their child through overfeeding.

Teen FUN

An increasing percentage of adolescents are now over-weight. As of 2018, around a third of UK children between 2 and 15 are clinically obese13 , and US childhood obesity has more than doubled in the past 25 years 14 . Increases in pre-diabetes and full-blown type 2 diabetes (T2D) in childhood is just one disease correlated with childhood obesity 15 . Unless dietary changes are made, T2D symptoms are likely to remain and increase as these young people pass into adulthood. This is made more probable by the fact that the medical professions are slow to change from viewing T2D as a life-long, irreversible condition – thereby their efforts are aimed at merely ‘managing’ the disease, rather than viewing it as a completely reversible condition if appropriate dietary and lifestyle changes are made and adhered to. 16

“Type 2 diabetes is rising rapidly in children and adolescents worldwide. Changing a child’s living environment to include physical activity, and a well balanced, low fat, high fiber diet, are important for the maintenance of a desirable body weight and improving insulin sensitivity…and decrease the risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.” 17

Fastest way to FUN

Just two words can sum up the major cause of FUN: ‘fast’ and ‘food’. Whether from take-aways, restaurants or supermarket shelves, fast food provides that perfect storm of high calories/low nutrients for children and adults alike.

Just two words can sum up the major cause of FUN: ‘fast’ and ‘food’. Whether from take-aways, restaurants or supermarket shelves, fast food provides that perfect storm of high calories/low nutrients for children and adults alike.

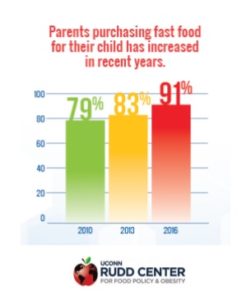

One of the key findings of a 2018 study into fast food purchases for children by their parents in the US was:

“Parents’ purchases of fast food for their children have increased in recent years:

- In 2016, 91% parents reported purchasing lunch or dinner for their child in the past week at one of the four largest fast-food restaurants, on average twice per week.

- In contrast, 79% reported purchasing fast food for their child in the past week in 2010.” 18

As far back as 2003, a US report 19 indicated that fast-food use was reported by 42% of children, resulting in:

- high intake of energy, fat, saturated fat, sodium, carbonated soft drinks, but

- low intake of vitamins A and C, fruits and vegetables

FUN leads to yo-yo dieting

This problem becomes compounded when the adolescents try to lose weight by attempting various restrictive dieting regimes – most of which fail and many of which exacerbate existing and/or create new health problems.

“Cross-sectional and prospective surveys have shown that a large percentage of adolescents, particularly females and even those of normal weight, diet at some time. While moderate changes in diet and exercise have been shown to be safe, significant psychologic and physiologic consequences may occur with extreme or unhealthy dieting practices. Moderate dieting has been shown to be associated with negative self-esteem in some adolescents. The very act of starting any diet increases the risk of eating disorders in adolescent girls. Extreme methods of weight loss can have adverse physiologic effects if not closely monitored. Electrolyte disturbances, cardiac dysrhythmias, and even sudden cardiac death can result from unhealthy or extreme dieting practices. Such practices are associated with other problem behavior in adolescents.” 20 .

A 2016 study 21 reported that, at any given time, more than 25% of male and around 60% of female adolescents are dieting in order to lose weight. In addition, up to 9% reported that they use maladaptive dieting habits, such as purging 22 .

Developing FUN in adulthood

It’s in so-called ‘developed’ countries that both children and adults are at particular risk from FUN.

Whilst a significant proportion (around 50%) of North Americans have inadequate intake of essential micronutrients and fibre, their energy balance is usually far in excess of physiological needs. And it’s been known for some time that adults shouldn’t only be worried about this FUN leading to obesity and T2D:

“Diet is estimated to contribute to about one-third of preventable cancers — about the same amount as smoking. Inadequate intake of essential vitamins and minerals might explain the epidemiological findings that people who eat only small amounts of fruits and vegetables have an increased risk of developing cancer. Recent experimental evidence indicates that vitamin and mineral deficiencies can lead to DNA damage.” 23

Energy density, portion size & availability

Standard foods, such as dairy, meat, sugar and vegetable oils tend to be more energy-dense in modern Western diets (often referred to as the SAD – Standard American Diet) when compared with the more traditional Asian and African diets, in which grains, legumes, and starchy vegetables play a much larger part.

Add to this the fact that, in Western societies, food portion sizes are larger and calorie dense/nutrient poor foods are much more easily available, and you have an adult population experiencing epidemic obesity-related diseases: coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer. 24

FUN into old age – if you last that long…

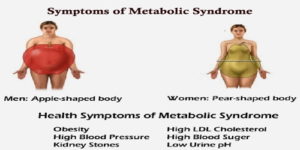

As our populations reach advanced age, metabolic syndrome 25 is becoming the norm rather than the exception, with more than 40% of people in their 60’s and 70’s being affected 26 and, thereby, running a greater risk of dying prematurely 27 .

As our populations reach advanced age, metabolic syndrome 25 is becoming the norm rather than the exception, with more than 40% of people in their 60’s and 70’s being affected 26 and, thereby, running a greater risk of dying prematurely 27 .

And dying isn’t even the worst of it. These chronic illnesses, during later years of one’s life, require regular hospitalisation, invasive, painful, and often humiliating medical procedures, restrictions of one’s privacy and independence, and severe limitations on the quality and enjoyment of one’s wise elderly years – years that should be active, happy and golden.

When the FUN stops

When you choose to eat a balanced WFPB diet, the FUN stops and the fun begins. Nutrient-rich foods become the norm and both micronutrients and macronutrients take care of themselves, with the ideal ratio of protein, fat and carbohydrate already wrapped up by nature with all the vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals and fibre that your body needs.

And no longer will you have to restrict how much you eat, nor worry about your weight, another paradox – albeit a very welcome one! – since, with such naturally healthy eating, you can’t help but get back to your ideal weight, thereby obviating the risk of falling into the cycle of yo-yo dieting.

Naturally, you’ll still be strongly advised to take B12 supplements and ensure you get enough sunlight, or else take vitamin D supplements; but apart from this, you can just concentrate on enjoying the rest of your life while your body and mind are naturally fuelled for optimal performance.

And all this by simply eating unadulterated plant foods…

References

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) . Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [↩]

- Piccoli, G., Clari, R., Vigotti, F., Leone, F., Attini, R., Cabiddu, G., … Avagnina, P. (2015). Vegan-vegetarian diets in pregnancy: danger or panacea? A systematic narrative review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 122(5), 623–633. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.13280 [↩]

- Maier JT et al: Antenatal body mass index (BMI) and weight gain in pregnancy – its association with pregnancy and birthing complications. J Perinat Med 44:397, 2016. [↩]

- Kabiru W, Raynor BD: Obstetric outcomes associated with increase in BMI category during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:928, 2004. [↩]

- Roseboom TJ et al: Effects of prenatal exposure to the Dutch famine on adult disease in later life: an overview. Mol Cell Endocrinol 185:93, 2001 [↩]

- Nicklas T, Johnson R, American Dietetic Association: Position of the American Dietetic Association: Dietary guidance for healthy children ages 2 to 11 years. J Am Diet Assoc 104:660, 2004 [↩]

- Jackson AA: Nutrients, growth, and the development of programmed metabolic function. Adv Exp Med Biol 478:41, 2000. [↩]

- N. Kapral, S. E. Miller, R. J. Scharf, M. J. Gurka, M. D. DeBoer. Associations between birthweight and overweight and obesity in school-age children. Pediatric Obesity, 2017 [↩]

- Pediatr Obes. 2014 Apr;9(2):135-46. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00155.x. Epub 2013 Apr 2. Socioeconomic status, infant feeding practices and early childhood obesity. Gibbs BG, Forste R. [↩]

- Matern Child Nutr. 2013 Jan;9 Suppl 1:105-19. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12010. Nutrition in pregnancy and early childhood and associations with obesity in developing countries. Yang Z, Huffman SL. [↩]

- Baird J et al: Being big or growing fast: systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. BMJ 331:, 2005 [↩]

- Ong KK et al: Dietary energy intake at the age of 4 months predicts postnatal weight gain and childhood body mass index. Pediatrics 117:e503, 2006. [↩]

- House of Commons Health Committee. Childhood obesity: Time for action. Eighth Report of Session 2017–19. Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report. Ordered by the House of Commons. 23 May 2018. [↩]

- Baird J et al: Being big or growing fast: systematic review of size and growth in infancy and later obesity. BMJ 331:, 2005. [↩]

- Whitlock EP et al: Screening and interventions for childhood overweight: a summary of evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics 116:e125, 2005 [↩]

- Diet Reverses Type 2 Diabetes – How Long Have We Known This? [↩]

- Vivian EM: Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents–the next epidemic? Curr Med Res Opin 22:297, 2006 [↩]

- UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity. Parents’ report of fast-food purchases for their children: Have they improved? September 2018. [↩]

- Paeratakul S et al: Fast-food consumption among US adults and children: dietary and nutrient intake profile. J Am Diet Assoc 103:1332, 2003 [↩]

- Starling P et al: Fish intake during pregnancy and foetal neurodevelopment–a systematic review of the evidence. Nutrients 7:2001, 2015 [↩]

- Zullig KJ, Matthews-Ewald MR, Valois RF: Weight perceptions, disordered eating behaviors, and emotional self-efficacy among high school adolescents. Eat Behav 21:1, 2016 [↩]

- Purging – a practice known as bulimia – oscillates with bingeing and can result in a wide range of health issues, including rupture of the oesophagus or stomach, dental and oral damage due to stomach acid exposing during vomiting. [↩]

- Ames BN, Wakimoto P: Are vitamin and mineral deficiencies a major cancer risk? Nat Rev Cancer 2:694, 2002 [↩]

- Isganaitis E, Lustig RH: Fast food, central nervous system insulin resistance, and obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25:2451, 2005 [↩]

- Metabolic syndrome is a combination of central obesity, dysglycaemia, dyslipidemia and arterial hypertension. Most of the disorders associated with metabolic syndrome have no visible symptoms except for a large waist circumference. Additional symptoms include increased thirst and urination, fatigue, and blurred vision. [↩]

- Arq Bras Cardiol. 2014 Mar; 102(3): 263–269. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Elderly and Agreement among Four Diagnostic Criteria. Maria Auxiliadora Nogueira Saad et al. [↩]

- Firdaus M: Prevention and treatment of the metabolic syndrome in the elderly. J Okla State Med Assoc 98:63, 2005 [↩]