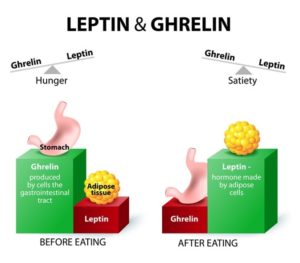

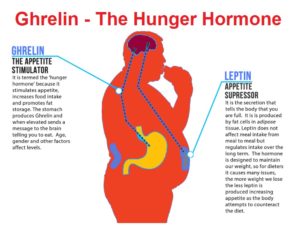

Increased appetite is a driving force for weight gain, and unchecked weight gain does, of course, lead to obesity. There’s a growing body of literature suggesting that ghrelin, the so-called “hunger hormone” or “starvation hormone”, plays an important role in appetite fluctuations. Whilst we looked at leptin, the “satiety hormone” in the previous blog 1 , this one is an analysis of some research on ghrelin and obesity 2 .

Because this is a rather complex blog, technical terms are in green – either click associated number to go to References/Notes section (blue arrow returns to same place in the text), or hold cursor over relevant number to reveal contents.

What is ghrelin?

The complexity of this topic starts as soon as one looks for the derivation of the word “ghrelin”, with some authorities 3 stating that it’s derived from “ghre” (grow) and “relin” (release), while another authorities4 appear to relate its etymological roots to the use of letters from its understanding as a “Growth Hormone RELease INducing” hormone. In any case, it is agreed that it was first isolated and identified by Kojima and Kangawa et al in 1999 5 . Three years later, its specific brain receptor, GHS-R 1a, was also identified 6 .

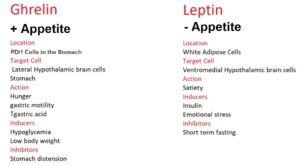

Whilst leptin is mainly secreted by fat cells 7 and insulin is secreted by beta cells in the islets of Langerhans within the pancreas, ghrelin is primarily secreted from cells in the stomach (see below for more detail on this).

Ghrelin vs leptin

Having already looked at leptin in the previous blog, it’s worth starting by drawing comparisons between it and ghrelin, since they are regarded as working together (although in opposite directions) to help regulate appetite and metabolism.

Ghrelin and leptin are the two hormones 8 that are most responsible for regulating appetite – to ensure you don’t eat too few calories and starve to death while also ensuring you don’t eat too many calories and become obese. Well, that’s the hope anyway!

As an appetite stimulant, ghrelin is called an orexigenic hormone9 that stimulates food intake and thereby helps regulate body weight, while the appetite-inhibiting hormone leptin is known as an anorexigenic hormone 10

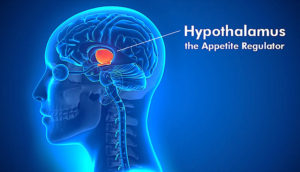

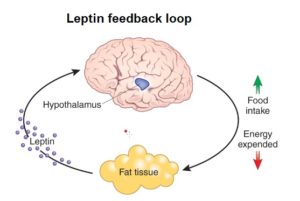

They are both homeostatic 11 hormones which means they are going to act on the hypothalamus 12 , the part of the brain that maintains the body’s internal balance (homeostasis).

They are both homeostatic 11 hormones which means they are going to act on the hypothalamus 12 , the part of the brain that maintains the body’s internal balance (homeostasis).

The hypothalamus acts as the link between the endocrine 13 and nervous 14 systems. The hypothalamus produces releasing and inhibiting hormones, which stop and start the production of other hormones throughout the body.

Ghrelin and leptin act on different parts (receptors) within the hypothalamus.

Ghrelin and leptin act on different parts (receptors) within the hypothalamus.

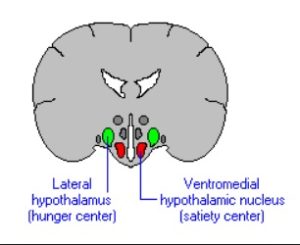

Ghrelin acts on the lateral 15 hypothalamic brain cells16 , while leptin acts on the ventromedial 17 hypothalamic brain cells.

“Ghrelin makes you Grow” – makes you eat, while “Leptin makes you Lean” – makes you stop eating. These are two mnemonics that might help to remember which is which.

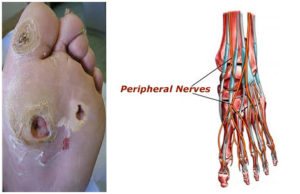

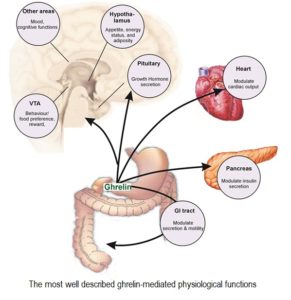

Ghrelin is the only peripheral 18 orexigenic hormone that activates receptors found in the appetite centre – viz. the hypothalamus and pituitary gland.

Ghrelin is produced by endocrine cells 19 of the oxyntic glands20 within the gastric fundus21 . It’s also secreted, to a lesser extent, by the body of the stomach, the mucosa of the duodenum and jejunum 22 , the lungs, the urogenital organs, and the pituitary gland.

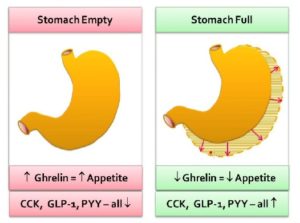

Once produced in the stomach, ghrelin is released into the bloodstream, passes through the blood-brain-barrier 23 to the lateral hypothalamus, and causes a hunger response.

Ghrelin will also have an effect on the stomach itself, causing an increase in gastric acid production and gastric motility 24 . This prepares the stomach for the food that’s been anticipated by the brain. Daily habits (breakfast, lunch and dinner) become ingrained so that our ghrelin production starts to increase before we’re even consciously aware that we’re hungry.

Ghrelin stimulants (or inducers) include hypoglycaemia (low blood glucose), an empty stomach, and low body weight (low body fat content).

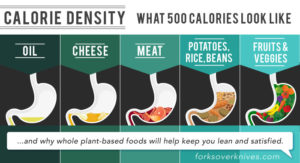

Ghrelin suppressants (or inhibitors) include activation of the stomach’s stretch receptors as the stomach becomes full of food (stomach distension).

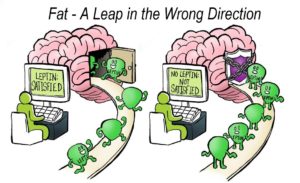

Leptin, on the other hand, is primarily produced by white adipose tissue.

Leptin, on the other hand, is primarily produced by white adipose tissue.

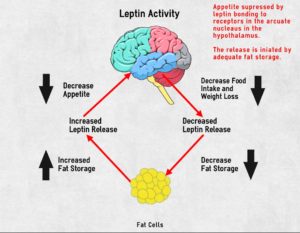

As the fat cells increase in size, they produce more leptin. A negative feedback signal 25 is caused when leptin travels from the fat cells, through the bloodstream and blood-brain-barrier to the ventromedial hypothalamic cells in the hypothalamus – reducing appetite and food intake. Ideally, this means that fat controls its own levels within the body. 26

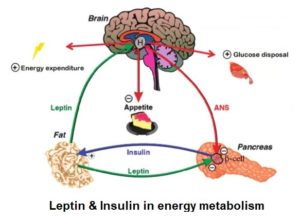

Inducers for leptin include insulin and emotional stress. Below, we consider how modern dietary changes may have messed with the normally healthy relationship between stress and hunger hormones.

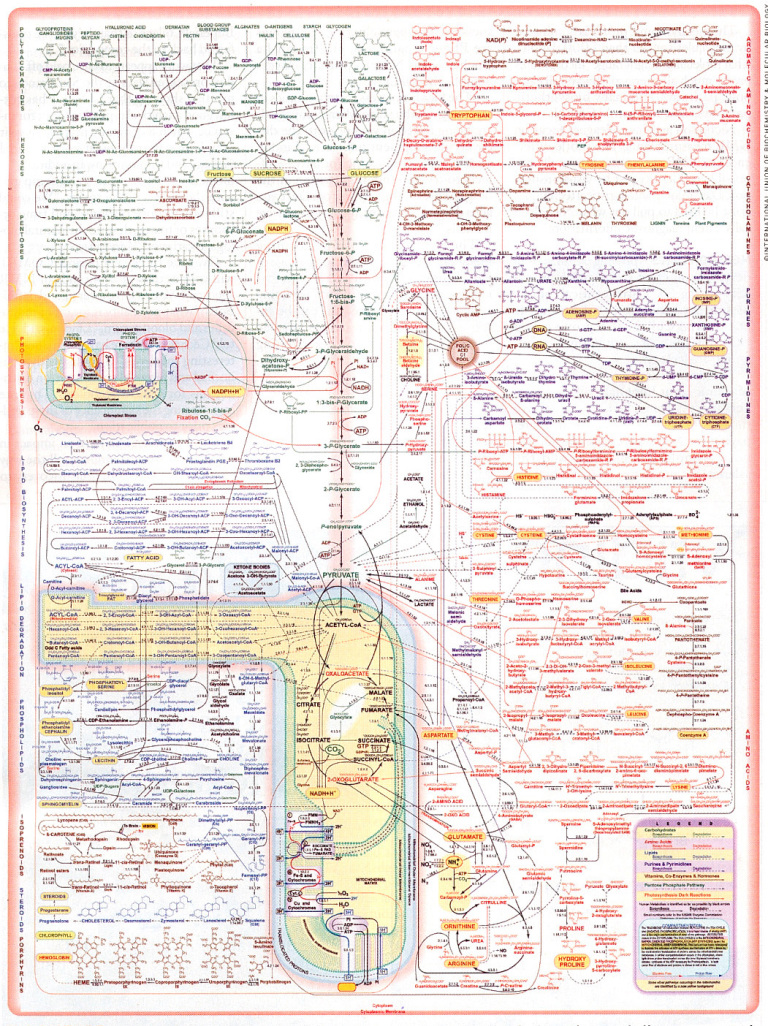

Leptin and insulin share common effects in controlling food intake and energy metabolism, with each playing an important role in blood glucose homeostasis. They directly regulate each other: leptin inhibits insulin and insulin stimulates leptin synthesis and secretion.

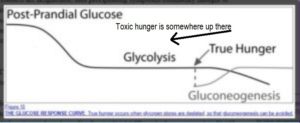

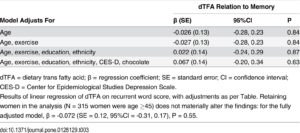

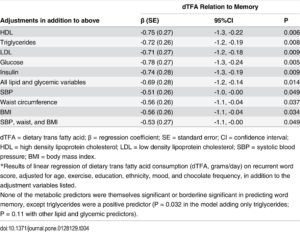

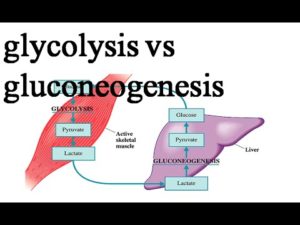

Leptin increases insulin sensitivity 27 , in part, by decreasing adiposity and lipotoxicity 28 . Leptin decreases hepatic (liver) production of glucose – glycogenolysis 29 – contributing to its glucose-lowering effects. 30

Studies have revealed that leptin has the effect of normalising hyperglycaemia 31 and hyperinsulinaemia 32 . It’s also clear 33 that levels of both need to drop for fat burning – i.e. gluconeogenesis 34 – to commence.

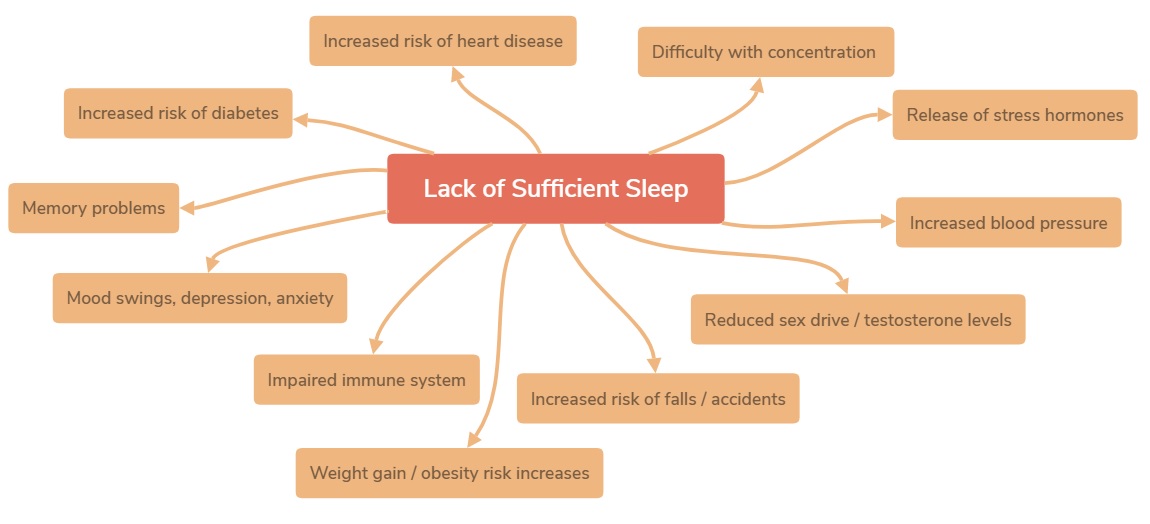

Whilst it would seem intuitively obvious in evolutionary terms that when the body is under stress (fight or flight), appetite for food would be switched off – perhaps causing the production of leptin to achieve this, studies 35 have pointed out a complication in the modern world with psychological stress: namely, that it often results in “comfort eating” (usually fatty, sweet, high calories foods). The latter modern habit can confuse the picture.

The previous blog pointed 1 out the paradox that obese humans tend to have higher levels of leptin – the hunger-inhibiting hormone – suggesting they have developed leptin resistance. This results in a toxic cycle of increased leptin insensitivity leading to increased leptin levels (irrespective of insulin and ghrelin levels) leading to increased amounts of fat being stored in the body, leading to the fat cells producing even more leptin.

To test the latter, researchers intravenously increased leptin levels during times of emotional stress in order to see whether this would lower the compensatory intake of such comfort food. They concluded that “…initial findings suggest that acute changes in leptin [i.e. increasing it in the short term] may be one of the factors modulating down [reducing] the consumption of comfort food following stress.” 36

A major inhibitor of leptin is short term fasting. When you haven’t eaten for several hours, leptin levels should drop and ghrelin levels should rise. A theory which appears to work okay in healthy, non-obese individuals.

Active & inactive ghrelin

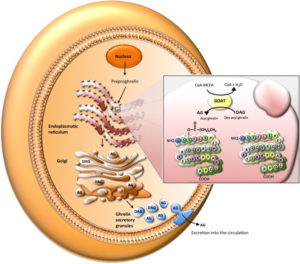

There are several different forms of ghrelin, but the main two are called the “inactive” (des-acyl ghrelin) and “active” (acyl ghrelin – a peptide of 28 amino acids) forms. The inactive form accounts for more than 90% circulating within the bloodstream 37 . However, the inactive form has to be converted into the active form in order to do its work as an appetite stimulant. It does this via an enzyme called ghrelin O-acyltransferase or GOAT 38 39 . This process is critical both for the orexigenic and the gastric-emptying actions of ghrelin.

How ghrelin exerts its effect on the body

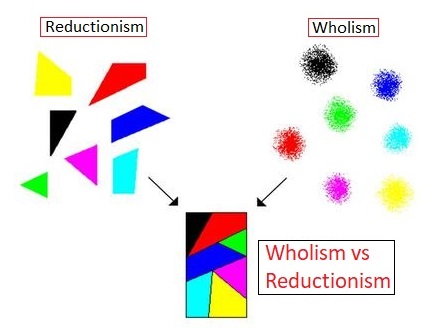

There are various possible actions by which ghrelin exerts its effect within the body, including:

- overproduction/underproduction of ghrelin before and/or after meals

- increased/decreased receptor sensitivity to ghrelin action

Ghrelin & positive feedback

The appetite-generating effect of ghrelin can be described as a direct positive feedback loop40 which maintains increased activity of AgRP neurons 41 so as to drive feeding behaviour until satiety is reached 42 , when leptin kicks in to do its job of suppressing appetite.

Other physiological functions of ghrelin

The discovery of the GOAT enzyme revealed that ghrelin is involved in many additional physiological functions, ranging from regulation of the immune and cardiovascular systems, up-regulation of insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), to a dominant role in the gastrointestinal system and involvement in gastric emptying and intestinal motility 43 .

The discovery of the GOAT enzyme revealed that ghrelin is involved in many additional physiological functions, ranging from regulation of the immune and cardiovascular systems, up-regulation of insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1), to a dominant role in the gastrointestinal system and involvement in gastric emptying and intestinal motility 43 .

Although it has a role as a growth factor secretagogue 44 , stomach-derived ghrelin doesn’t appear to be necessary for growth and appetite stimulation, since ghrelin-deficient animals still appear to grow and eat quite normally 45 .

There must, therefore, be some form of redundancy within the body – that is, other physiological processes that promote growth and appetite which are able to compensate for the absence of ghrelin.

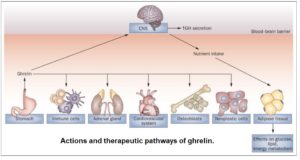

Actions and therapeutic pathways of ghrelin for gastrointestinal disorders

As can be seen in the diagram, ghrelin affects multiple systems. Whilst being secreted mainly by the stomach, it has effects in multiple areas, including the CNS (central nervous system), the immune system, the adrenal gland and the cardiovascular system. It can also affect the proliferation of osteoblasts 46 and neoplastic cells 47 .

As can be seen in the diagram, ghrelin affects multiple systems. Whilst being secreted mainly by the stomach, it has effects in multiple areas, including the CNS (central nervous system), the immune system, the adrenal gland and the cardiovascular system. It can also affect the proliferation of osteoblasts 46 and neoplastic cells 47 .

Ghrelin, obesity & appetite

The precise role of ghrelin in the pathophysiology of obesity is still under investigation. It’s considered by some that if we’re able to get a firm grip on how ghrelin initiates appetite, then increasing its level could be a revolutionary new method of obesity management and treatment.

Reduced postprandial suppression of ghrelin in obese individuals

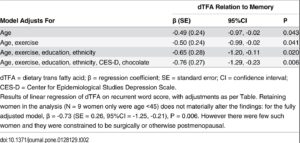

In a number of studies of obese adults and obese children 48 49 , it’s been reported that postprandial suppression of ghrelin is lower in such obese groups compared to controls with normal body mass index (BMI).

This makes it a reasonable assumption that higher consumption of food by obese individuals is linked to a continuing feeling of hunger, even after consuming a meal with sufficient caloric content to satisfy their physiological needs. These findings have supported the ‘disease pattern’ of obesity which has underlying mechanisms and causes like other common disorders.

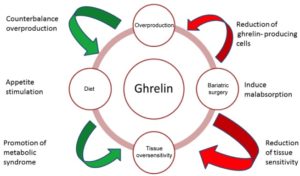

What’s the problem with ghrelin in relation to obesity?

So, is the obesity-ghrelin problem (and, by inference, the insulin-ghrelin problem) a matter of an overproduction of ghrelin or is it similar to what we’ve seen with leptin and insulin – i.e. insensitivity leading to resistance?

Since studies (mentioned above) 45 have shown that animals completely deficient in ghrelin can still grow normally without becoming obese, it would seem that the likeliest problem is the overproduction of ghrelin (regardless of the how much food is consumed) rather than a ghrelin insensitivity or oversensitivity. Various studies support this hypothesis 50 51 52 , although uncertainty still remains regarding the precise mechanism/s involved, which range from a possible dysfunction in the gene for ghrelin to the production of antibodies to the peptide receptors which antagonise 53 ghrelin’s effects which, in turn, might lead to disturbances in the production and actions of ghrelin. Additionally, interactions with other hormones (insulin, growth hormone (GH), etc) are likely to account for at least some of the ghrelin-obesity anomalies.

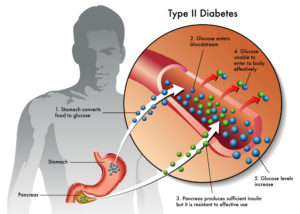

We still don’t fully understand the relationship between ghrelin and insulin – a relationship which appears to be based on an overproduction of ghrelin leading to a similar overproduction and eventual insensitivity/resistance to insulin 54 .

The view that the obesity-ghrelin problem is not due to an overproduction of ghrelin in obese individuals is supported by many studies. showing that the mean serum ghrelin level is generally lower in obese patients compared to lean individuals 55 56 , although the number of ghrelin-producing cells was found to be more abundant in the fundus of morbidly obese patients.

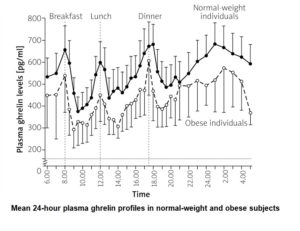

You’d be excused for expecting obese individuals to have lots more of this appetite-promoting hormone floating around their bloodstream than would non-obese individuals, given that the former continue eating beyond their physiological needs. And you wouldn’t be alone. The following graph 57 reveals that, though ghrelin levels rise in expectation of a meal and fall after that meal in both obese and non-obese individuals, the levels of ghrelin are consistently higher in non-obese than in obese individuals.

A further study concluded: “Contrary to our hypothesis, however, obese subjects have lower plasma concentrations of the adipogenic 58 hormone ghrelin than age-matched lean control subjects.” 59

The same study made some suggestion about what’s actually happening with ghrelin in obese individuals, suggesting that it may be a downregulation 60 of ghrelin as a consequence of elevated insulin or leptin, because fasting plasma ghrelin levels are negatively correlated with fasting plasma levels of insulin and leptin.

They also speculated that decreased secretion of ghrelin could be responsible for decreased levels of circulating growth hormone (GH) 61 in obese individuals 62 .

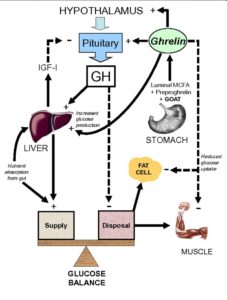

Ghrelin, growth hormone (GH), diabetes & obesity

Ghrelin, as stated above, causes the release of growth hormone (hence the proposed origin of its name – Growth Hormone Release Inducing hormone). The relationships between obesity, adipose tissue, GH and ghrelin make an already complex situation even more complex.

Ghrelin, as stated above, causes the release of growth hormone (hence the proposed origin of its name – Growth Hormone Release Inducing hormone). The relationships between obesity, adipose tissue, GH and ghrelin make an already complex situation even more complex.

Obesity induces hyperinsulinaemia, hypoadiponectinaemia 63 , hyperleptinaemia 64 , reduced serum ghrelin, and increased free fatty acid levels. The effect of this is that GH secretion from the pituitary gland is suppressed 65 .

But what’s the relationship between low levels of GH and ghrelin in obese/diabetic individuals?

Insulin resistance is highly associated with visceral obesity, non-alcoholic liver disease, and type 2 diabetes. In turn, all these conditions are associated with low GH secretion. Since high levels of GH are likely to contribute to the development of insulin resistance when, that is, caloric intake is greater than physiological demand (when you eat more calories than you burn), the body’s reduction in GH secretion in obesity may be an adaptive phenomenon which is aimed at preventing insulin resistance occurring.

However, a problem occurs with this situation: namely, when GH secretion is reduced, it’s likely to lead to further increases in fat accumulation by reducing the process of lipolysis 66 . It’s clear to see how this increased retention of fat can exacerbate obesity and establish a dangerous vicious circle. Indeed, truncal adiposity 67 is one of the most important clinical findings of a condition known as adult GH deficiency syndrome (GHD) 68 .

So, when levels of circulating GH are reduced, as they are in cases of obesity, it’s proposed 59 that decreased plasma ghrelin concentrations – which are seen in obesity – represent a physiological adaptation to the positive energy balance 69 associated with this disease.

GH (like insulin) is essential in adapting the utilisation of calories to the amount of ingested food, promoting anabolism 70 in the case of positive energy balance, with catabolism 71 occurring in the case of negative energy balance 72 . While insulin is the main metabolic hormone in the fed state (positive energy balance), GH assumes a key role as stimulator of lipolysis during prolonged fasting (negative energy balance), when it causes preferential oxidation of lipids and protein synthesis 73 .

“The increase in GH secretion that occurs with fasting may have represented an evolutionary advantage in times of food scarcity. However, GH and IGF-I have opposite effects on glucose homeostasis, with the former reducing insulin sensitivity (mainly acting in the liver) and the latter increasing it in the muscle.” 74

Plenty more detail on the relationship of ghrelin and GH is available in a number of excellent studies 75 .

Ghrelin and diets

As you’d expect, levels of ghrelin increase during dieting. This could explain why it’s very difficult to achieve long-term success from dieting. 76 77

Two way to manage obesity

There are two main approaches in managing obesity:

- conservative – e.g. diet, exercise and lifestyle changes

- surgical – through various weight-loss surgical procedures, widely known as bariatric surgery

The conservative ways of preventing and treating diabetes, primarily through dietary changes, have been covered in such detail in previous blogs 78 79 80 81 that we hardly need to repeat them here.

Ghrelin & bariatric surgery

It’s clear that bariatric surgery is going to cause some purely mechanical effects (less room for food) that would be responsible for subsequent increased food restriction, as well as often leading to malabsorption 82 . After all, the person concerned has had bits of their guts removed and/or joined together. However, during the past couple of decades, the identification of significant humoural 83 changes (that lead to less hunger or earlier satiety postprandially) has complicated the picture of why appetite changes occur after such surgical procedures 84 48 .

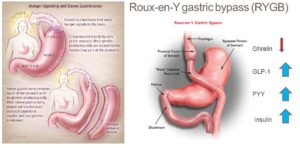

Ghrelin & two types of bariatric surgery

Researchers have recently tried to explain the impressive results of bariatric surgery in terms of weight loss by evaluating the changes in ghrelin concentration following roux-en-y gastric bypass (RYGB) 85 and especially sleeve gastrectomy (SG) 86 . In the latter procedure, the gastric fundus, where most ghrelin is produced, is totally removed. A recent meta-analysis 51 showed that the ghrelin level does fall significantly following SG. In patients who undergo RYGB, the results of various studies are contradictory 87 .

Does bariatric surgery work?

Both these techniques lead to exceptionally good results in weight loss. Based on the fact that, anatomically, SG is purely restrictive compared to RYGB, which additionally creates malabsorption by the rapid shunt of undigested food to the distal small intestine 88 , the role of ghrelin is now being investigated more than ever. Whether or not bariatric surgery works, we know that even morbidly obese individuals can return to a normal healthy weight without the need for such extreme dietary measures 89 . Additionally, once the body is back to a healthy homeostatic state, one would assume that ghrelin levels would also normalise.

Ghrelin & age-related obesity

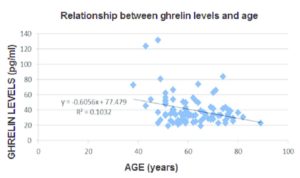

The adjacent graph 90 shows that ghrelin levels decrease with age, backed up by other studies 91 . This would be in line with the fact that ageing is accompanied by a decrease in both energy expenditure and locomotor activity – with decreases in muscle strength and endurance leading to functional decline. The latter factors, taken in isolation, would imply that there would be a corresponding increase in body weight, particularly in the form of fat.

The adjacent graph 90 shows that ghrelin levels decrease with age, backed up by other studies 91 . This would be in line with the fact that ageing is accompanied by a decrease in both energy expenditure and locomotor activity – with decreases in muscle strength and endurance leading to functional decline. The latter factors, taken in isolation, would imply that there would be a corresponding increase in body weight, particularly in the form of fat.

This has an effect on food intake as well as energy expenditure, thereby potentially preventing the development of age-related obesity. 92

Ghrelin and anorexia

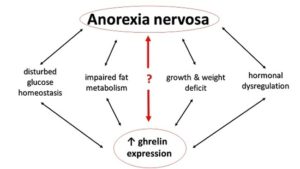

Due to the proven relationship of ghrelin with appetite, researchers are also investigating the potential connection of ghrelin to anorexia. Insight into the modification of the endogenous ghrelin system seems to be promising not only for the control of obesity, but also for the management of clinically significant anorexia and pathological weight reduction.

Due to the proven relationship of ghrelin with appetite, researchers are also investigating the potential connection of ghrelin to anorexia. Insight into the modification of the endogenous ghrelin system seems to be promising not only for the control of obesity, but also for the management of clinically significant anorexia and pathological weight reduction.

Does anorexia produce ghrelin insensitivity?

Accumulating evidence has shown that in patients with anorexia nervosa, there’s a paradoxical increase in plasma ghrelin level even when compared with matched controls or obese patients 93 , suggesting that the situation may be one of ghrelin-insensitivity 94 .

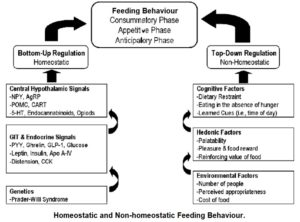

Ghrelin – homeostatic and non-homeostatic feeding

Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa 95 and other eating disorders appear to have pathophysiologies 96 linked to dysfunctions of reward mechanisms. 97 Additional research 98 supports the hypothesis that ghrelin doesn’t just increase appetite by homeostatic need – that is, feeding driven by a metabolic need where hormones “speak to one another” in order to create homeostatic balance, but also by non-homeostatic feeding – that is, feeding driven by non-metabolic factors, such as reward (“hedonic feeding” 99 ) and memory. The latter factors have less to do with the body trying to reach homeostatic balance than with emotional, psychological and social factors.

Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa 95 and other eating disorders appear to have pathophysiologies 96 linked to dysfunctions of reward mechanisms. 97 Additional research 98 supports the hypothesis that ghrelin doesn’t just increase appetite by homeostatic need – that is, feeding driven by a metabolic need where hormones “speak to one another” in order to create homeostatic balance, but also by non-homeostatic feeding – that is, feeding driven by non-metabolic factors, such as reward (“hedonic feeding” 99 ) and memory. The latter factors have less to do with the body trying to reach homeostatic balance than with emotional, psychological and social factors.

Tail wagging the dog

The huge increase in the consumption of ultra-processed foods (high in sugar/fat/calories and low in nutrients) could be regarded as a causal factor in the dysregulation of homeostatic hormonal systems (ghrelin, leptin, insulin, etc), resulting in the tail (learned emotional need) wagging the dog (actual physiological need). This results in our medical professions struggling to cope with the ever-increasing effects of diet-related diseases, and in millions of suffering people who end up with diseased bodies and shortened lives.

Cancer and ghrelin administration

In vitro studies 100 have documented that both intra-peritoneal 101 and systemic 102 administration of ghrelin have the potential of improving appetite and nutritional status, and at the same time reducing the metabolic rate in patients with end-stage cancer.

This research suggests a likelihood that additional gastric disorders (e.g. gastritis, GI tract carcinoma, and other functional GI disorders) disrupt the morphological structure 103 of the stomach, and thus alter ghrelin production – being that the stomach is its major source. “These alterations may induce various GI disorders including functional GI disorders, eating disorders, abnormal energy homeostasis and growth. By understanding ghrelin secretion in the regulation of GI disorders, ghrelin levels may serve as a good diagnostic biomarker for early detection of GI disorders.” 100

The roles that ghrelin may play in relation to cancer is still relatively unclear. One study concludes: “It is currently unclear whether the ghrelin axis has tumor-promoting effects, or indeed whether it may inhibit tumorigenesis in vivo, and further studies are therefore required to elucidate its role in cancer.” 104

Limitations of Studies Investigating Ghrelin

There are several limitations in investigating ghrelin:

- very small number of studies and RCTs (randomised controlled trials)

- there are two forms of circulating ghrelin, inactive ghrelin (90%), and active acylated ghrelin (10%) 50 and published studies tending to measure total rather than active ghrelin levels

- the active form of ghrelin has been reported to be unstable at room temperature

- there’s a current lack of standardisation in ghrelin measurement in terms of timing of sample collection, collection method, follow-up period, sample storage, and the radioimmunoassays 105 being used

The latter issues make precise measurement a challenge and this may be an issue in the reproducibility of results in the future.

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS)

PWS, a congenital form of obesity, is caused by a mutation on chromosome 15. One of the effects of this is that ghrelin levels are hugely increased and the individual is forever hungry. If untreated, eating far, far too much – resulting in morbid obesity. It’s thought 106 that elevated ghrelin levels in PWS children precede the onset of obesity.

Prader-Willi syndrome vs non-congenital obesity

When ghrelin levels were compared between children with PWS and children with non-congenital obesity (i.e. nothing wrong with their chromosome 15), it was found 107 that, even immediately after eating meals, ghrelin levels remained comparatively much more elevated in the PWS children.

The reason for this is speculated 108 to be that hyperghrelinaemia 109 in early infancy might be a response to the failure to thrive, and that chronic or persistent hyperghrelinaemia eventually promotes hyperphagia (overeating) in early childhood. 110

Once again, it would appear that more complexity has befallen us, since the obesity in PWS individuals is accompanied by elevated levels of ghrelin in the blood, while in non-congenitally obese individuals, ghrelin levels appear to be reduced even compared with non-obese individuals.

Further research on ghrelin

Whilst ghrelin research is ongoing, and all will hopefully be made clearer in the near future, a two-part YouTube video 111 112 presents a very detailed analysis of the discovery of ghrelin and its receptor, along with its relationship to GH and its role in starvation-prevention.

Final thoughts

The above is by no means a comprehensive analysis either of the specific role/s of ghrelin in the development of obesity nor of its other varied physiological roles. Indeed, I haven’t even touched on another important appetite-suppressing hormone, namely PYY 113 . Its relationship with ghrelin and other hormones is sufficiently complex to warrant a separate analysis, although there are plenty of studies for the interested reader. 114 115 116

What is clear, though, is that ghrelin appears to be attracting attention with regard to the treatment of obesity.

However, it does continue to be a source of irritation that, within the realm of medical research, so much emphasis is directed towards treatment (usually through searches for pharmaceutical and/or gene-based solutions) rather than prevention. And, as strong evidence suggests, obesity is best treated through dietary change; with the most effective and long-lasting dietary change being one that increases the ratio of whole plant foods to processed and/or animal foods 117 118 119 .

My expectation is that most research dollars will be spent on developing highly-profitable pharmaceutical solutions for perceived problems that relate to ghrelin and associated hormones. The elephant in the room is dietary change, of course. When we looked at toxic hunger vs real hunger 120 , we merely touched on the issue of ghrelin. However, it would seem relevant to this discussion to consider that eating a WFPB diet – which has significant impact on both homeostatic (the physiological effects of hormones, etc) and non-homeostatic feeding (‘comfort eating’ and ‘addictive’ dietary habits) – would also have direct and/or indirect effects on the effectiveness of the ghrelin-leptin-insulin-GH axis. Once again, more research is needed in this area, although where the research dollars come for this type of research is likely to be an ongoing problem.

References & Notes

- Leptin – The “Fat” Hormone? [↩] [↩]

- In Vivo. 2017 Nov-Dec;31(6):1047-1050. Ghrelin and Obesity: Identifying Gaps and Dispelling Myths. A Reappraisal. Makris MC, Alexandrou A, Papatsoutsos EG, Malietzis G, Tsilimigras DI, Guerron AD, Moris D. [↩]

- Walker A K, Gong Z, Park W M, Zigman J M, Sakata I. Expression of Serum Retinol Binding Protein and Transthyretin within Mouse Gastric Ghrelin Cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64882. [↩]

- Open University: The Science of Nutrition& Healthy Eating. [↩]

- Methods Enzymol. 2012;514:3-32. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381272-8.00001-5. History to the discovery of ghrelin. Bowers CY. [↩]

- Hormones (Athens). 2016. Effects of ghrelin in energy balance and body weight homeostasis. Mihalache L, Gherasim A, Niţă O, Ungureanu MC, Pădureanu SS, Gavril RS, Arhire LI. [↩]

- Leptin is mainly secreted by adipocytes (fat cells) of white adipose tissue. It’s also produced in brown adipose tissue, placenta syncytiotrophoblasts, ovaries, skeletal muscle, the lower part of the fundic glands within the stomach, mammary epithelial cells, bone marrow, gastric chief cells and P/D1 cells. [↩]

- A hormone is any member of a class of signalling molecules produced by glands in multicellular organisms that are transported by the circulatory system to target distant organs to regulate physiology and behaviour. [↩]

- Orexigenic – An orexigenic, or appetite stimulant, is a drug, hormone, or compound that increases appetite and may induce hyperphagia – overeating. This can be a naturally occurring neuropeptide hormone such as ghrelin, orexin or neuropeptide Y, or a medication which increases hunger and therefore enhances food consumption. [↩]

- Anorexigenic – an anorexigenic hormone reduces or inhibits appetite. [↩]

- Homeostasis is the state of steady internal conditions maintained by living things. This dynamic state of equilibrium is the condition of optimal functioning for the organism and includes many variables, such as body temperature, fluid balance, blood sugar levels, and body weight being kept within certain pre-set limits. [↩]

- The hypothalamus is an endocrine gland. Endocrine glands within the endocrine system secrete their products, hormones, directly into the blood rather than through a duct. The major glands of the endocrine system include the pineal gland, pituitary gland, pancreas, ovaries, testes, thyroid gland, parathyroid gland, adrenal glands and, of course, the hypothalamus. [↩]

- The endocrine system is a chemical messenger system consisting of hormones, the group of glands of an organism that secrete those hormones directly into the circulatory system to regulate the function of distant target organs, and the feedback loops which modulate hormone release so that homeostasis is maintained. [↩]

- The nervous system is the part of an animal that coordinates its actions by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes that impact the body, then works in tandem with the endocrine system to respond to such events. [↩]

- Lateral means of, at, towards, or from the side or sides. The green cells on the diagram. [↩]

- specifically, on the cell receptor known as the ghrelin/growth hormone secretagogue receptor or GHS-R. Secretagogue receptors are those that promote secretion. [↩]

- Ventral means on or relating to the underside of an animal, plant or object – in this case the brain; while ventromedial indicates that it’s situated towards the middle of the ventral part. The red cells on the diagram. [↩]

- Peripheral – that is, produced or taking place outside of the central nervous system , CNS – i.e. outside the brain and spinal cord [↩]

- International Journal of Peptides. Volume 2010, Article ID 945056, 7 pages. Ghrelin Cells in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Ichiro Sakata, Takafumi Sakai. [↩]

- Oxyntic glands – these are made up of secretory cells which produce hydrochloric acid in the main part of the stomach, or the glands which they compose [↩]

- the upper part of the stomach, which forms a bulge above the level of the opening of the oesophagus, furthest from the pylorus [↩]

- Duodenum and jejunum are the first and second parts of small intestine, with the ileum being the final part before entering the large intestine, the colon. [↩]

- The blood-brain barrier is a semipermeable membrane separating the blood from the cerebrospinal fluid, and constituting a barrier to the passage of cells, particles, and large molecules. Only specific substances, including ghrelin, are able to pass through this barrier. [↩]

- Gastric or gastrointestinal motility is defined by the movements of the digestive system, and the transit of the contents within it. [↩]

- A negative feedback (or balancing feedback) signal occurs when some function of the output of a system, process, or mechanism is fed back in a manner that tends to reduce the fluctuations in the output, whether caused by changes in the input or by other disturbances. [↩]

- (Morton G. J., Schwartz M. W. (2011). Leptin and the central nervous system control of glucose metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 91, 389–411. [↩]

- Kamohara S., Burcelin R., Halaas J. L., Friedman J. M., Charron M. J. (1997). Acute stimulation of glucose metabolism in mice by leptin treatment. Nature 389, 374–377 10.1038/38717 [↩]

- Lipotoxicity is a metabolic syndrome that results from the accumulation of lipid intermediates in non-adipose tissue, leading to cellular dysfunction and death. The tissues normally affected include the kidneys, liver, heart and skeletal muscle. [↩]

- Glycogenolysis is the breakdown of the molecule glycogen into glucose, a simple sugar that the body uses to produce energy. The opposite of glycogenolysis is glycogenesis, which is the formation of glycogen from molecules of glucose. [↩]

- Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Dec; 16(Suppl 3): S549–S555. Leptin therapy, insulin sensitivity, and glucose homeostasis. Gilberto Paz-Filho, Claudio Mastronardi, Ma-Li Wong, and Julio Licinio. [↩]

- Hyperglycaemia is an excess of glucose in the bloodstream, often associated with type 2 diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus. [↩]

- Hyperinsulinaemia is a condition in which there are excess levels of insulin circulating in the blood relative to the level of glucose. While it is often mistaken for diabetes or hyperglycaemia, hyperinsulinemia can result from a variety of metabolic diseases and conditions. [↩]

- Cell. Volume 172, issue 1, P234-248.E17, January 11, 2018. Leptin Mediates a Glucose-Fatty Acid Cycle to Maintain Glucose Homeostasis in Starvation. Rachel J. Perry et al. [↩]

- Gluconeogenesis is is a metabolic pathway that results in the generation of glucose, to be burned as energy, from certain non-carbohydrate carbon substrates, including fat and protein. [↩]

- Physiol Behav. 2012 Aug 20; 107(1): 34–39. Leptin concentrations in response to acute stress predict subsequent intake of comfort foods. A. Janet Tomiyama et al. [↩]

- Physiol Behav. 2012 Aug 20;107(1):34-9. Leptin concentrations in response to acute stress predict subsequent intake of comfort foods. Tomiyama AJ et al. [↩]

- Total and active ghrelin levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. S. Ferrero P. Anserini V. Remorgida G. Bentivoglio N. Ragni. Human Reproduction, Volume 21, Issue 2, 1 February 2006, Pages 565. [↩]

- GOAT is essential for ghrelin-mediated elevation of GH, necessary to prevent death from severe calorie restriction through preservation of blood glucose levels. [↩]

- Ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT) is essential for growth hormone-mediated survival of calorie-restricted mice. Zhao TJ, Liang G, Li RL, Xie X, Sleeman MW, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Apr 20; 107(16):7467-72. [↩]

- Positive Feedback – a physiological cyclic process or action that can continue to amplify the body’s response to a stimulus until a negative feedback response, its opposite, takes over. [↩]

- AgRP neurons – brain neurons that make agouti-related peptides – hence AgRP – that potently stimulate food intake [↩]

- Hunger Circuit. Science Signalling. stke.sciencemag.org/content/4/192/ec269 by W Wong – 2011. [↩]

- Intestinal mobility is the movements of the digestive system, and the transit of the contents within it. [↩]

- A secretagogue is a substance that stimulates secretion of another substance – in this case, ghrelin stimulates the release of growth factor (GH) from the pituitary gland. [↩]

- Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006 Dec;7(4):237-49. Role of endogenous ghrelin in growth hormone secretion, appetite regulation and metabolism. Dimaraki EV, Jaffe CA. [↩] [↩]

- Osteoblasts are the cells required for bone synthesis and mineralisation, both during the initial formation of bone and during bone remodelling. [↩]

- A neoplasm is an abnormal new growth of cells. The cells in a neoplasm usually grow more rapidly than normal cells and will continue to grow if not treated. [↩]

- Dimitriadis E, Daskalakis M, Kampa M, Peppe A, Papadakis JA, Melissas J. Alterations in gut hormones after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective clinical and laboratory investigational study. Ann Surg. 2013;257(4):647–654. [↩] [↩]

- Wiley Online Library: Obese children aged 4–6 displayed decreased fasting and postprandial ghrelin levels in response to a test meal. Jenny Önnerfält, Charlotte Erlanson‐Albertsson, Caroline Montelius, Kristina Thorngren‐Jerneck. 24 November 2017. [↩]

- Camilleri M, Papathanasopoulos A, Odunsi ST. Actions and therapeutic pathways of ghrelin for gastrointestinal disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6(6):343–352. [↩] [↩]

- Anderson B, Switzer NJ, Almamar A, Shi X, Birch DW, Karmali S. The impact of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on plasma ghrelin levels: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2013;23(9):1476–1480. [↩] [↩]

- Groschl M, Uhr M, Kraus T. Evaluation of the comparability of commercial ghrelin assays. Clin Chem. 2004;50(2):457–458. [↩]

- An antagonist is a substance which interferes with or inhibits the physiological action of another. [↩]

- Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology

Volume 340, Issue 1, 20 June 2011, Pages 26-28. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. Review. Ghrelin in Type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome. [↩] - Abdemur A, Slone J, Berho M, Gianos M, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Morphology, localization, and patterns of ghrelin-producing cells in stomachs of a morbidly obese population. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24(2):122–126. [↩]

- Vincent RP, le Roux CW. Changes in gut hormones after bariatric surgery. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69(2):173–179. [↩]

- ResearchGate. The role of gastrointestinal hormones in the pathogenesis of obesity and Type 2 diabetes. May 2014. [↩]

- Adipogenesis is the formation of adipocytes (fat cells) from undifferentiated fibroblasts (preadipocytes). Fibroblasts are cells that are responsible for producing connective tissues in the body. [↩]

- Circulating Ghrelin Levels Are Decreased in Human Obesity. Matthias Tschöp, Christian Weyer, P. Antonio Tataranni, Viswanath Devanarayan, Eric Ravussin, Mark L. Heiman. Diabetes 2001 Apr; 50(4): 707-709. [↩] [↩]

- Downregulation is the process of reducing or suppressing a response to a stimulus. In this case, it’s a reduction in a cellular responses to ghrelin molecules due to changes in the number of activity of receptors. [↩]

- Growth hormone is released from the pituitary gland to cause growth in children and affects bone density, lipid metabolism, and muscle in children and adults, stimulating amino acid uptake and protein synthesis in muscle and other tissues. Because a major role of growth hormone is to to stimulate the liver and other tissues to secrete IGF-1, this can be a problem if too much IGF-1 is produced in adults. Due to its insulin-like properties, IGF-1 can have serious and potentially fatal health effects including: diabetic (hypoglycaemic) coma, heart palpitations (tachycardia), facial nerve pain or paralysis (Bells Palsy), swelling of the hands, and so forth. [↩]

- Maccario M, Grottoli S, Procopio M, Oleandri SE, Rossetto R, Gauna C, Arvat E, Ghigo E: The GH/IGF-I axis in obesity: influence of neuroendocrine and metabolic factors. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord (Suppl. 2):96–99, 2000 [↩]

- Hypoadiponectinaemia is characterised by low plasma adiponectin levels – a protein hormone that is produced by fat cells. Its physiological effects include the reduction of inflammation and atherogenesis (the formation of fatty deposits in the arteries) and enhancement of the response of cells to insulin. [↩]

- Hyperleptinaemia is the presence of a higher than normal amount of leptin in the bloodstream. [↩]

- S. Savastano, C. Di Somma, L. Barrea, A. Colao, The complex relationship between obesity and the somatropic axis: the long and winding road. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 24, 221–226. 2014. [↩]

- Lipolysis is the breakdown of lipids and involves hydrolysis of triglycerides into glycerol and free fatty acids. It mainly occurs in adipose tissue, and is used to mobilise stored energy during fasting or exercise. [↩]

- Truncal adiposity refers to obesity – fat retention – around the trunk of the body. [↩]

- M.E. Molitch, D.R. Clemmons, S. Malozowski, G.R. Merriam, M.L. Vance, Evaluation and treatment of adult growth hormone deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, 1587–1609. 2011. [↩]

- Positive energy balance occurs when the intake of food is greater than the output of work (as in muscular or secretory activity). The result is that the body stores extra food as fats. Negative energy balance occurs when the body draws on stored fat to provide energy for work. [↩]

- Anabolism is a process a process that involves the synthesis of complex molecules from simpler molecules. These processes produce growth and differentiation of cells and increases in body size. Examples of anabolic processes include the growth and mineralisation of bone and increases in muscle mass. [↩]

- Catabolism is the set of metabolic pathways that breaks down molecules into smaller units that are either oxidised to release energy or used in other anabolic reactions. [↩]

- Negative energy balance is when energy demands exceed caloric supply – the opposite of positive energy balance. [↩]

- A.A. Sakharova, J.F. Horowitz, S. Surya, N. Goldenberg, M.P. Harber, K. Symons, A. Barkan, Role of growth hormone in regulating lipolysis, proteolysis, and hepatic glucose production during fasting. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 2755–2759. 2008. [↩]

- Endocrine. June 2015, Volume 49, Issue 2, pp 304–306. Growth hormone deficiency in patients with obesity. Roberto Salvatori. [↩]

- Ghrelin and growth hormone: Story in reverse. Ralf M. Nass, Bruce D. Gaylinn, Alan D. Rogol, and Michael O. Thorner. PNAS May 11, 2010 107 (19) 8501-8502. [↩]

- Cummings DE, Weigle DS, Frayo RS, Breen PA, Ma MK, Dellinger EP, Purnell JQ. Plasma ghrelin levels after diet-induced weight loss or gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(21):1623–1630. [↩]

- Geloneze B, Tambascia MA, Pilla VF, Geloneze SR, Repetto EM, Pareja JC. Ghrelin: a gut-brain hormone: effect of gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2003;13(1):17–22. [↩]

- Can The UK Government Really Combat Child Obesity? [↩]

- England’s Obesity Hotspots [↩]

- Vegan Pregnancy & Parenting [↩]

- Bliss Points, Pleasure Traps & Wholefood Plant-Based Diets [↩]

- Malabsorption occurs when the small intestine can’t absorb enough of certain nutrients and fluids – including macronutrients – proteins, carbohydrates, and fats – and micronutrients – vitamins and minerals – or both [↩]

- relating to the body fluids, especially with regard to immune responses involving antibodies in body fluids as distinct from cells [↩]

- National Task Force on the Prevention Treatment of Obesity Overweight, obesity, and health risk. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(7):898–904. [↩]

- Roux-en-y gastric bypass (RYGB) – from César Roux, the surgeon who first described it – a form of anastomosis – an anastomosis is a connection or opening between two things that are normally diverging or branching, such as between blood vessels, leaf veins, or streams – involving a division of the small intestine, resulting in a Y-shaped configuration [↩]

- Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG) – a surgical weight-loss procedure in which the stomach is reduced to about 15% of its original size, by surgical removal of a large portion of the stomach along the greater curvature. [↩]

- Liou JM, Lin JT, Lee WJ, Wang HP, Lee YC, Chiu HM, Wu MS. The serial changes of ghrelin and leptin levels and their relations to weight loss after laparoscopic minigastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2008;18(1):84–89. [↩]

- The distal small intestine is the part furthest from the stomach – the ileum. [↩]

- Morbid Obesity Solution: A Long-Term Plant-Based Case Study. Nutritionstudies.org. 24 Jan 2017. [↩]

- ResearchGate. Serum ghrelin level is associated with cardiovascular risk score. Romanian journal of internal medicine. 53(2):140-5 · September 2015. [↩]

- Aging Cell. 2017 Aug;16(4):859-869. doi: 10.1111/acel.12618. Epub 2017 Jun 6. Deletion of ghrelin prevents aging-associated obesity and muscle dysfunction without affecting longevity. Guillory B1, Chen JA, Patel S, Luo J, Splenser A, Mody A, Ding M, Baghaie S, Anderson B, Iankova B, Halder T, Hernandez Y, Garcia JM. [↩]

- Aging Cell. 2017 Aug; 16(4): 859–869. Deletion of ghrelin prevents aging‐associated obesity and muscle dysfunction without affecting longevity. Bobby Guillory et al. [↩]

- Korek E, Krauss H, Gibas-Dorna M, Kupsz J, Piatek M, Piatek J. Fasting and postprandial levels of ghrelin, leptin and insulin in lean, obese and anorexic subjects. Prz Gastroenterol. 2013;8(6):383–389. [↩]

- Mequinion M, Langlet F, Zgheib S, Dickson S, Dehouck B, Chauveau C, Viltart O. Ghrelin: central and peripheral implications in anorexia nervosa. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013;4:15. [↩]

- Bulimia nervosa is an emotional disorder characterised by a distorted body image and an obsessive desire to lose weight, in which bouts of extreme overeating are followed by fasting or self-induced vomiting or purging. [↩]

- Pathophysiology or physiopathology is the disordered physiological processes associated with disease or injury. [↩]

- ResearchGate. Getting to the bottom of feeding behaviour: Who’s on top? Applied Physiology Nutrition and Metabolism 32(2):177-89 · May 2007. [↩]

- Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013 Mar. Dysfunctions of leptin, ghrelin, BDNF and endocannabinoids in eating disorders: beyond the homeostatic control of food intake. Monteleone P, Maj M. [↩]

- Cell Metabolism. Volume 27, issue 1, P42-56, January 09, 2018. Overlapping Brain Circuits for Homeostatic and Hedonic Feeding. Mark A. Rossi, Garret D. Stuber. [↩]

- Cheung CK, Wu JC. Role of ghrelin in the pathophysiology of gastrointestinal disease. Gut Liver. 2013;7(5):505–512. [↩] [↩]

- Intra-peritoneal means within or administered through the peritoneum – the thin, transparent membrane that lines the walls of the abdominal (peritoneal) cavity and contains/encloses the abdominal organs such as the stomach and intestines [↩]

- systemic administration is a route of administration of medication, nutrition or other substance into the circulatory system so that the entire body is affected. Administration can take place via either, 1. enteral, that is, via the gastrointestinal tract by oral, sublingual, oesophagus, stomach, small/large intestine and rectum, or by 2. parenteral administration, that is via means that bypass the gastrointestinal tract, mainly by intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intravenous injections that bypass skin and mucous membranes [↩]

- Morphology is a branch of biology dealing with the study of the form and structure of organisms and their specific structural features. [↩]

- The Ghrelin Axis—Does It Have an Appetite for Cancer Progression? Lisa K. Chopin Inge Seim Carina M. Walpole Adrian C. Herington. Endocrine Reviews, Volume 33, Issue 6, 1 December 2012, Pages 849–891. [↩]

- radioimmunoassay is a technique for determining antibody levels by introducing an antigen (a toxin or other foreign substance which induces an immune response in the body, especially the production of antibodies) labelled with a radioisotope and measuring the subsequent radioactivity of the antibody component [↩]

- Feigerlová E, Diene G, Conte-Auriol F, et al. Hyperghrelinemia precedes obesity in Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:2800-5. 10.1210/jc.2007-2138 [↩]

- Gumus Balikcioglu P, Balikcioglu M, Muehlbauer MJ, et al. Macronutrient Regulation of Ghrelin and Peptide YY in Pediatric Obesity and Prader-Willi Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:3822-31. 10.1210/jc.2015-2503 [↩]

- Am J Med Genet A. 2015 Jan;167A(1):69-79. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36810. Epub 2014 Oct 29. Hyperghrelinemia in Prader-Willi syndrome begins in early infancy long before the onset of hyperphagia. Kweh FA, Miller JL, Sulsona CR, Wasserfall C, Atkinson M, Shuster JJ, Goldstone AP, Driscoll DJ. [↩]

- Hyperghrelinaemia is, as the name suggests, an abnormally high level of ghrelin. [↩]

- Transl Pediatr. 2017 Oct; 6(4): 274–285. Review of Prader-Willi syndrome: the endocrine approach. Ryan Heksch, Manmohan Kamboj, Kathryn Anglin,Kathryn Obrynba. [↩]

- Surviving Starvation: The Ghrelin-Growth Hormone Axis. Part 1. [↩]

- Surviving Starvation: The Ghrelin-Growth Hormone Axis. Part 2. [↩]

- PYY (Peptide YY or peptide tyrosine tyrosine) – a peptide that in humans is encoded by the PYY gene. Peptide YY is a short peptide released from cells in the ileum and colon. Soon after eating, and before food reaches the lower small intestine (ileum), PYY is secreted into the blood by cells lining the ileum and colon. [↩]

- Nature. 2002 Aug 8;418(6898):650-4. Gut hormone PYY(3-36) physiologically inhibits food intake. Batterham RL, Cowley MA, Small CJ, Herzog H, Cohen MA, Dakin CL, Wren AM, Brynes AE, Low MJ, Ghatei MA, Cone RD, Bloom SR. [↩]

- Braz J Med Biol Res. 2012 Jul; 45(7): 656–664. Correlations of circulating peptide YY and ghrelin with body weight, rate of weight gain, and time required to achieve the recommended daily intake in preterm infants. XiaFang Chen et al. [↩]

- J Physiol. 2009 Jan 1; 587(Pt 1): 19–25. The role of peptide YY in appetite regulation and obesity. Efthimia Karra, Keval Chandarana, Rachel L Batterham. [↩]

- J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017 May; 14(5): 369–374. A plant-based diet for overweight and obesity prevention and treatment. Gabrielle Turner-McGrievy, Trisha Mandes, and Anthony Crimarco. [↩]

- CNS. Morbid Obesity Solution: A Long-Term Plant-Based Case Study. By Roberta Russell. January 24, 2017. [↩]

- Nutritionfacts.org: Obesity. [↩]

- Toxic Hunger vs Real Hunger [↩]